One of the most intriguing aspects of Florence is its ability to hide-sometimes in plain sight-many of its most special treasures.

Take the church and monastery of San Marco. Founded in the thirteenth century, the complex was enlarged in 1437, when Dominican monks from Fiesole moved there at the invitation of Cosimo il Vecchio. Not known for scrimping, Cosimo spent a considerable sum to have his favorite architect, Michelozzo, completely rebuild the monastery. Its simple cloisters and cells, masterpieces themselves, were made immortal when one of the friars, Fra Angelico, completed a series of remarkable devotional frescoes from 1438 to 1445. The convent increased its notoriety in the mid- to late-fifteenth century as the home of firebrand monk Girolamo Savanarola and his crusade against immorality.

Yet today, as tourists and school groups make their way through Piazza San Marco, they see little hint of the former tranquillity of the monastery’s exterior and setting. A hub for many of the city’s public transportation lines, the piazza is hot and congested. Most tour groups head straight for the Fra Angelico frescoes, often bypassing what is undoubtedly one of Florence’s greatest overlooked treasures: the cloister of Sant’Antonino.

Ironically, every visitor to San Marco must go through the cloister, built in 1440 by Michelozzo, to enter the church of San Marco and the monastery. Typically, however, they move quickly through the narrow hallway lined with eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sepulchral monuments and tombstones, out the door and past the large cedar, planted in the last century, that thrives in the middle of the cloister, which introduces the elegant monastery, an outstanding example of orderly Florentine Renaissance architecture.

The loggia rests on five columns per side, decorated with majestic ionic capitals and low arches that create a rhythm proportional to human dimensions and suggest a secluded space. The serene rhythm is echoed by small, single windows on the first floor, each indicating a friar’s cell. This overall simplicity and reciprocity is repeated in the colors of the principal materials used: white lime, grey stone, red brick. The fresco of St. Dominic worshipping the Crucifixion, painted by Fra Angelico opposite the entrance is uplifting.

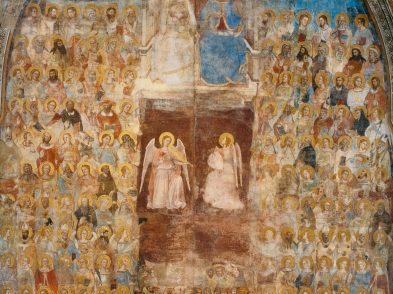

Originally, this, with the five little lunettes above the door, was the only painted image that decorated the white cloister. During the seventeenth century the monks of San Marco decided to celebrate the figure of Sant’Antonino-a person of great moral, religious and civic stature who was also largely responsible for the rebirth of the monastery, of which he was prior from 1439 to 1445 (see box). The most famous Florentine painters of the time were commissioned to paint a cycle of lunettes depicting scenes from the life of the saint. Several noble Florentine families paid for the work, and their coats-of-arms appear in the frescoes. The empty spaces around Fra Angelico’s lunettes were painted with allegories and figures complementary to the main scene.

These frescoes of Sant’Antonino and the surrounding cloister-overlooked treasures in plain view-are the focus of a major restoration project supported by the Friends of Florence.

THE RESTORATION

According to Magnolia Scudieri, director of the Museum of San Marco, the restoration of the Sant’Antonino lunettes and medallions is no ordinary project. Over the last few centuries, some of the art world’s most famous restorers worked on the frescoes, thereby rendering the cycle unique on the basis of its restoration history alone. Additionally, like many of Florence’s most prized possessions, the cloister and its artwork are under siege from the emissions from the constant, heavy traffic that passes through the piazza every day.

‘Because of the particular nature of the frescoes, their numerous restorations and environmental issues, we were not interested in rushing into restoring them again just for the sake of it. I wanted to study the problem and create a solution as unique as the frescoes themselves,’ said Scudieri.

She took her suggestion to a neighbour: the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, the autonomous entity of the Italian Ministry for Cultural Heritage and renowned conservation institute. Her unusual proposal to have one of the Opificio’s students complete a thesis on the restoration of the cloister’s frescoes was accepted immediately. ‘It was important that a thorough study be done before we began any sort of hands-on work,’ commented Scudieri, ‘At the time the thesis was completed, we had not yet asked for funding; we went forward with the idea of restoring one lunette at a time.’

However, when Simonetta Brandolini d’Adda, founder and director of the Friends of Florence approached the museum about financing the restoration, Dr. Scudieri was impressed with the group’s sensitivity and ability to understand the unique nature of the project: ‘These works make the city what it is today,’ said Scudieri. The Friends of Florence, recognizing that it is often the less ‘visible’ works that need the most attention, decided to finance the restoration of all of the lunettes, medallions and the Michelozzo columns on the south side of the cloister. Two members of Friends of Florence, Ellen and James Morton, are funding the entire restoration.

THE RESTORERS

Brandolini d’Adda, has commented that she delights in taking visitors to the cloister of Sant’Antonino to see the work in progress and meet the restorers, both of whom have a unique connection to the cloister and to San Marco, which makes their work even more intriguing.

Giacomo Dini is the grandson of Dino Dini, one of Italy’s foremost restoration experts and the inventor of the ammonium-barium method still used today. Thirty years ago, when Dino completed the important restoration of Fra Angelico’s works in San Marco, his sixteen-year-old grandson Giacomo was by his side. After training under his famous grandfather, young Giacomo completed his studies and took over the family business, Dini Restauri, founded in 1926. Methodical and patient, the new expert in the Dini family has made a name for himself with numerous prestigious restorations carried out all over Italy. He is now back at work in the very cloister where his education began, perhaps with his grandfather’s voice gently guiding him.

His partner in the restoration is Bartolomeo Ciccone, the Opificio student who undertook the research on the Sant’Antonino cloister requested by Dr. Scudieri. Though he looks no older than a high school student, Ciccone’s expertise and enthusiasm are forces to be reckoned with. He can tell you every date, the history of each figure in the lunettes, and every painstaking detail of each restoration carried out through the centuries. His connection is more recent than Giacomo’s, but he makes his way through the cloister and the monastery, as though at home.

The two men and their work on what is one of Florence’s ‘hidden’ masterpieces are testament to the immense effort required in conserving the city’s artistic heritage-an effort that Friends of Florence generously, and knowledgeably, supports.

SANT’ANTONINO

Antonio Pierozzi was born to a noble Florentine family in 1389. Because of his diminutive stature, his fellow citizens dubbed him ‘Antonino’ (‘Little Anthony’)-the nickname has officially replaced his baptismal name. He joined the Domenican order at the age of 15 and became a monk in Fiesole before taking various posts in the Dominican order. He founded the San Marco convent in Florence in 1436. By 1446, his unique combination of saintly character and administrative skills had led to the position of archbishop of Florence, a role he held until his death in 1459. He was canonized by Pope Adrian VI in 1523. A street in the San Lorenzo area is named after him and the Church of Sant’Antonino is located in piazza Rosadi (near Bellariva).