Daphne Maugham fell in love with artist Felice Casorati long before the couple met, thanks to a painting he had produced of Cynthia, her dancer sister, while she was a prima ballerina at Turin’s private Teatro Gualino. Recognizing a maestro from afar, Maugham moved to Turin in 1925 so she could learn to paint in a style that hinged on a love for classicism and exalted unusual perspectives. By 1931 the couple would be married.

In reality, art was part of Maugham’s genetic makeup. Her maternal grandfather, Heywood Hardy, was a noted animal painter, while her great-grandfather, Sir William Beechey, had served as a portraitist in the court of Queen Victoria. Daphne herself was the third female in her immediate family to become a visual artist: her sister Clarisse was also a painter as was her mother Mabel Hardy, known as ‘Beldy,’ whose fabric genre scenes can be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and Jeu de Paume in Paris.

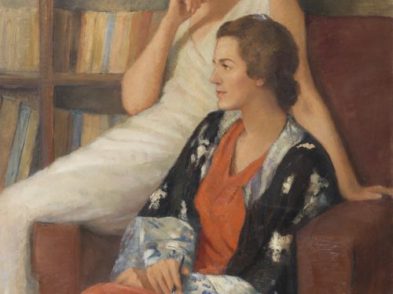

In 1925, Maugham joined her sister in Turin and quickly became Casorati’s stellar pupil sharing a class-studio with other women of note, including Paola Levi Montalicini, Giorgina Lattes and Nella Marchesini, who would particularly admire ‘the unforced naturalness of her portraits.’ As Casorati recounted, ‘Daphne was born to paint and I to cerebrally construct a painting … It is my belief that, as her teacher, I received from her the best and most healthy human and artistic lesson. I would admire Daphne, who painted with simple joy.’

The studio’s international atmosphere suited Maugham. Before graduating from London’s Slade School of Art in 1922, she had lived in Paris for seven years, attending the city’s prestigious Academie Rason, run by Nabis founder Paul Sèusier and the movement’s keynote theoretician, Maurice Denis, who spearheaded nonrepresentational art and upheld the philosophies of Paul Gauguin. She would later credit Denis for giving a spiritual dimension to her work. Maugham’s education continued from 1918 to 1921 at the Accademie Notre-Dame des Champs with Cubist painter Andre Lhote, who had also trained Art Deco exponent Tamara de Lempicka. While in Paris, Maugham frequented the salon of self-taught post-Impressionist painter Mela Munter, whom a French critic praised as ‘being like Goya if he could have painted like Van Gogh.’ Munter was one of the first Polish women to devote herself professionally to painting, and her atelier attracted the likes of Berthe Morisot, Diego Rivera and Rainer Maria Rilke. Maugham felt at home there. As the daughter of a prosperous British diplomat and a vivacious musician-artist, she was fluent in four languages. These skills would serve her well nearly a decade later, when, as Casorati’s wife, she would play host to Turin’s most accomplished intellectuals.

Accomplished and self-assured, Maugham had nine exhibitions at the Venice Biennale between 1928 and 1950, as well as six exhibitions at the Quadriennale Nazionale d’Arte in Rome between 1935 to 1965. She received numerous prizes throughout her career, including the Fiorino Prize at the Florence’s Accademia Gallery.

Maugham’s work was also exhibited in Palazzo Strozzi in 1967 during Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti’s famed exhibition Modern Art in Italy (1915–1935). This noteworthy show, organized after the Arno’s devastating flooding in 1966, drew attention to one of Ragghianti’s most celebrated initiatives: to gather works by local and international artists in order to salvage and replace art the city had lost in the flood. According to said project, artwork that was not sold would become part of Florence’s Contemporary Art Museum, a promise that has yet to reach fruition. Though currently in storage as part of the city’s Civic Collections, Maugham’s In the Garden (1934) is an attractive example of her interest in plein-air paintings, the genre for which she is most often celebrated.

It is interesting to note that Maugham would not sign her painting with anything other than ‘Daphne.’ Perhaps she used her first name to avoid being overshadowed by her husband’s larger-than-life persona. He, not she, was the family’s designated artist. She also willingly shed the weighty fame of her maiden name, possibly because it immediately recalled her caustic paternal uncle, William Somerset Maugham, the most popular, highest-paid writer of his era, who had penned The Razor’s Edge and Of Human Bondage. (An interesting sidenote: Somerset Maugham, who came to Florence in 1895 to study Italian, originally wrote his Florence-based romantic thriller Up at the Villa for an American women’s magazine, whose editor snubbed the novella as ‘not at all what readers would want.’)

Uncle and niece shared several character traits: both were known as quiet, observant souls. Yet, their philosophies on art and beauty were somewhat contrasting. For Somerset Maugham, beauty was ‘something wonderful and strange that the artist fashions out of the chaos of the world in the torment of his soul. And when he has made it, it is not given to all to know it.’ His niece’s views were far less exclusive: ‘It’s possible for any person to carry within his own life this thing called art, all he has to do is get into the habit of thinking with his own head … all he has to do is get used to observing and reflecting in a simple way,’ Daphne Maugham wrote. ‘In short, it is enough to be one’s self and, as Krishnamurti says, to never be anything besides what you are, because any pose or affectation hinders truth from shedding its light through us.’