This essay, L’altra Firenze by Vanni Santoni, was originally published in The Towner. Translation into English by Helen Farrell.

Florence, Florence. “Do you still live in Florence?” was the word on the street ten years ago, as if those who were born here should get the hell out of town. Quickly followed by, “You should write about it!” Which is subtext for, “If you dare to stay, then at least talk about it”.

Certainly it’s true that for those who live here it’s always something of a surprise that Florence continues to attract people, and that some of these actually stay. Not just the people who are offloaded from a never-ending trail of buses every day on lungarno della Zecca Vecchia and who are then marched on an unchanging tour of the Ponte Vecchio, Palazzo Vecchio, Uffizi, Duomo and the fistful of basilicas that are shoved into their day, if there’s any time left after spending up at the charmless markets and along the big-brand shopping streets. It’s normal that these places exist, after all: this is mass tourism, the curse and the blessing, the nourishment and the Big C of Florence.

It would be wonderful if things weren’t like that and if Florence, as journalist Giovanni Papini hoped a hundred years ago, were to free itself from the weight of its past, if it could stop living “on the shoulders of the dead and the barbarians” and return to being a cradle of geniuses. It might not be capable of doing so, however. To stay on the safe side, Florence carries on exactly the same as 400 years ago, and what actually surprises us, the people who live here, isn’t so much the influx of tourists but the arrival of those convinced that they’ll find something new, another Florence. Therefore it comes as a surprise to us when we do find something, without even knowing what it is. Indeed, we actually deny that there is something left to find. The hills around Florence, and the town itself, still brim with aspiring artists, poets, writers and architects, not only locals but people from all around the world, choosing and hoping that these hills will bestow upon them the education they crave, if not a spiritual elevation.

This choice might seem absurdly wrong to us, a fatal mistake. What elevates an artist is peer exchange, and indeed it’s the praxis by those of us who have embarked on an artistic path—and which we justify to ourselves by saying that we chose Florence just because it was close when we had to choose where to study—to leave for varying lengths of time, when we can afford it, to go to world capitals, or just to Rome or Milan, in pursuit of that exchange (those galleries, literary cafes or publishing houses) that Florence does not offer because of close-knit circles of friends and acquaintances.

It’s not a bad decision because Florence’s cultural substratum is what it is, narrower than what you find in a metropolis. In comparison with other cities of the same size, there are certainly more magazines, exhibitions and events; there’s even an international circle—as dedicated as it is to knocking back shots. It’s just wrong because everything that Florence has to offer, as a last resort, is itself, and this concept isn’t easy to grasp, and certainly not in a few months.

On Ponte Santa Trinita there’s a young guy; he has that Anglo-Saxon look about him. He’s got everything he needs: Clarks-style shoes, but artisan-made; a jacket with patches on the elbows; a light linen sweater, almost Indianesque, underneath. He’s sitting on the bridge: it’s a beautiful clear day, a stone’s throw away the Ponte Vecchio is reflecting in the water. Windows, domes and bell towers peek out all over the place: it’s a show stealer, let’s face it, today’s light on the Arno. There’s even that rare breeze—it’s all here, he has it all, and there he is pulling out a notebook (or a sketchpad, camera or tripod complete with canvas cover).

He’ll write bullshit down in that notepad; an irredeemable daub will take shape on that canvas. It’s not his fault of course, and we’ve all been in his shoes a couple of times at least. Masterpieces cannot be reproduced and they cannot speak for themselves—the Ponte Vecchio or Santo Spirito, or even just the churches of Cestello or Ognissanti cannot be depicted without ending up straightaway on a postcard or in an imitative painting. The charms presented by Boccaccio and Dante aren’t there ready to prostitute themselves to the first passer-by, regardless of how much prostitution does go on in the city. That “business” has always been there, after all.

When the American sculptor Greg Wyatt gave his statue Two Rivers to the city—the Arno and the Hudson, the river in New York where the artwork had seemingly made the big time and the river of Florence where Wyatt had studied—the culture councillor at that time (to think that nowadays Florence doesn’t even have one) joked that he was going to put it on eBay, and was accused of being arrogant and unseemly. No, it wasn’t a declaration of eternal love, but the councillor was right. What could the city have done with that bronze, without at best smacking it on some roundabout out near Novoli? (In the end it was exiled to Pisa.)

The fact remains that Florence is a finished work, the ultimate masterpiece. The most it can do is make way, like a smartass, for a passing Koons, which can ridicule the mayor with his installation but not remotely the city, and will eventually leave town, and quickly too. Spectres of giants walk along the city streets, the marbles stand there keeping guard and those who pass through, or those who stay, or those who live here can be nothing more than mould, or a cockroaches. No strolling here. Forget it. If you’re a tourist, we don’t want to know. Passing through on your way somewhere else? If you live here strolling gets on your nerves. It’s tiring; that’s something you learn after years of being here. Intimacy with the city occurs at the oddest of times: loafing around on the night of August 16 or at 5am on a weekday, walking home after being left on the viali by someone who gave you a lift after a night out, or finding your way back to the centro storico from Rifredi at night when you muddled up the final destination of an Intercity.

After having found yourself more than once in such predicaments—a fact that coincides with having lived at length in Florence—and only after such situations have become mixed up with less obvious and more evocative places, loaded with a power that has been lost elsewhere, crystallized in souvenir images, in old photographs, in places symbolic of the city, which stand for nothing. Like the tenebrous river of borgo Pinti and the winding via Romana, like via Maffia, a dead end with an enigmatic doorway, and the silent via San Gallo, a skinny slash that nevertheless manages to be charming; like the steep via dell’Erta Canina and costa San Giorgio, which lead to another city, a different place that offers a picture of past Florence.

These places are nothing special, of course. I failed to mention that the only truly complete view of Florence is the one from the Vasari Corridor, that to understand the city you need to have a full understanding of the esoteric codes hidden in the Torrigiani Gardens and that the only sensible way to arrive at the Oblate from Santa Maria Nuova is through the underground tunnel. I mentioned ordinary places: even out-of-towners know via San Gallo, for instance. But these simple places go unappreciated: cut off by the tourist gangrene that eats away at everything, they become mere blowholes. Only when the city is deserted at last, or when it sleeps, like fairies that encounter a child alone at last in the woods, lost at last, something reminiscent of a sign system re-emerges.

Those who want to begin, those who truly want to try to believe in this city, to do something with it, rapidly realize that to facilitate a similar process you have to cross the Arno before you do anything else. Newcomers always begin in piazza del Duomo or Santa Croce: that’s mistake number one. Humans are savvy enough to shirk off placenta and afterbirth, so they are clever enough to cross a bridge and start in piazza Santo Spirito. On the other side of the Arno things don’t change that much; it’s as if there were a leftover shadow, a suspicion of life. A gut feeling underlined by the papers too: if you’re murdered on the right side of the Arno, it’s normal, the usual savage crime, “But what has the world become?” But if a murder occurs in the Oltrarno, the idea of a dark, bohemian, alternative (voiced in the most hostile way, verging on the malevolent) neighbourhood bursts forth. We hear about it in the papers, on the radio, in the miserable local television reports, even in conversation, in chiacchiere.

It’s all nonsense of course. But if locals are that upset, if they’re that worked up about it, it means that there must be something good here that still hasn’t been located and eliminated, or maybe the mood on this side of the river is just different, and better. It’s not that the typical atmosphere of piazza Santo Spirito—if “typical” means a regurgitation of bistros and restaurants seemingly less commercial than their counterparts in piazza della Passera and in borgo San Frediano, which still likes to make out that it’s working class in writer Vasco Pratolini style—is actually that authentic. It’s just a little less fake, by virtue of a fistful of residents who still actually try to live there, despite all attempts to push them out, doing away with gardens, facilities and parking.

It would be easy to describe what the Oltrarno does not have: the other side of the Arno is “better” because there’s no San Lorenzo or Porcellino market, no groups and souvenir shops, high street fashion and fast food outlets; it’s better than some eateries at the epicentre of the disgrace, where pasta is peddled out of microwaves and fluorescent ice-cream sold at astronomical prices. The truth is that Florence, even though we maybe shouldn’t say it, is a city with a secret soul, and Santo Spirito is, albeit not by much, simply the most secret of its two parts, slightly more concealed and shadowy, slightly less crowded and congested.

The first time I realized this was here in this very neighbourhood. I’d been living in Florence for a couple of years and had been invited to dinner on the highest floor of one of the tallest buildings in via Maggio, another dark river, even during the day. I went out onto the balcony, which was actually the roof, and looked outside. I had been expecting the usual Florentine skyline, so beautiful it stuns or sickens you, the view you simply have to photograph from piazzale Michelangelo. I expected the only difference to be a more central perspective, like when you climb Giotto’s bell tower or the tower at Palazzo Vecchio. What I saw was something else. For the first time I realized that almost every city block had at its centre a garden. Small ones, enormous ones: the very palazzo where I was standing concealed a sizeable garden, unimaginable from the outside, with pine and palms, and even a private playground.

Or not. Maybe we need to turn it all round: get out of the centre, break free from the hard-boiled shell, walled in as though the still standing gates power a force field around us, break away from the knots of people and the secret gardens, cross the allotments, get out, open our arms, and find new intersections around outer symbols, such as the English Cemetery, San Salvi Park, Ponte alle Riffe, or even Viadotto dell’Indiano.

Or go farther still, take the plunge and be led into the plains, beyond Novoli, Peretola and Sesto Fiorentino, all places where students have been rerouted in the latest act of self-destruction, from city centre cloisters to suburban campuses. Continue, keep going, past the industrial zone of Osmannoro, find some truth there, like the English and French caravans did as they came through here 20 years ago to the beat of free tekno, as if subconsciously transforming the entire Florence-Scandicci-Sesto-Osmannoro-Campi-Prato-Pistoia area into a single enormous conurbation, all interstitial, whose centre forms the emptiest and most anonymous point. Perhaps those folks ended up in Prato, only realising they were no longer in Florence due to the writing on prefab walls that had mutated into ideograms, like in Blade Runner…

What will we find, however, if none other than a post-industrial periphery no different to any other, albeit less impressive and far less alienating? On the Bologna bypass there’s a whole other scale; in Brianza the industrial zones are unending, they extend kilometre after kilometre. What’s the point of our flyovers compared to those in Paris or even in nearby Milan, to the polished and dazzling viaducts of Stockholm, the technological constructs of Tokyo and Houston, or the unimaginable enormity of those in Shanghai? Here the meaning has coagulated elsewhere, and we are forced to reckon with the centro storico, pietra forte sandstone, and white and green marble.

But what can we do? Celebrate them? It would be grotesque and ridiculous, unless you had to base an electoral campaign upon them. Finding an epigraph for this essay was an effort in itself: among countless quotations, one more nauseating than the other, I was sorely tempted to coin a famous Warhol citation or one from surly Ezra Pound (“Florence, the most damned city in Italy where there’s nowhere to sit, stand or walk”). But even criticism always risks being superficial, like all self-celebratory literary inspiration. Do the likes of Dante, Boccaccio, Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Michelangelo and Cellini (it’s sickening even to list them) really need us to tell them how brilliant, how bravi they were? It would be a sick joke, like the statues in the niches at the Uffizi, niches intended to be empty as an austere architectural feature, yet which fell prey to a zealous nineteenth-century printmaker, a certain Vincenzo Batelli, who launched a campaign to fill them, and now we see them all there, in their long johns, one alongside the other. Not even Lorenzo the Magnificent is missing.

No, it’s not possible. The fact remains, as things stand, the only way to love Florence is to hate her, and the only way to speak about her is to step aside, look down and occasionally allow yourself a glance at a spire beyond the rooftops, a glimpse that disappears at the end of an almost straight street.

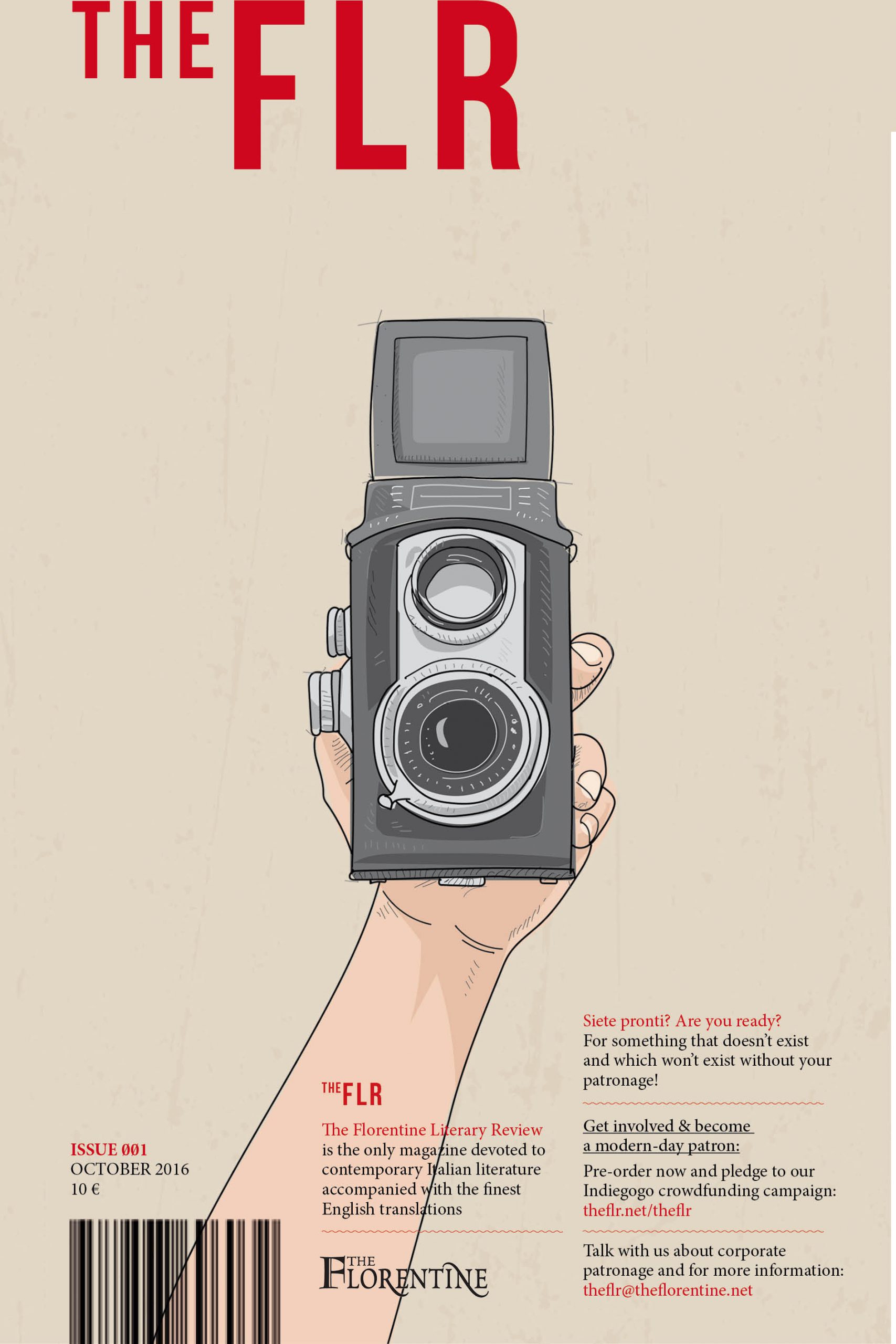

This translated essay is the type of writing you can expect to read in The Florentine’s forthcoming bilingual literary review, TheFLR. The Florentine Literary Review. Help us to spread the word about contemporary Italian literature in translation.