A Renaissance historian walks into a medical library, but not all who wander are lost. At New York’s Stony Brook University, a modern printing of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings sits on a shelf made significant only by its blatantly apparent lack of use. Perhaps the book belongs in a humanities library, lest a wandering medical student take its contents as truth. The Leonardo da Vinci. Anatomies: Machines, Human Body, Nature exhibition at Montepulciano Fortress (open until October 7) invites us to revisit these drawings with attention to how Da Vinci conceptualized the body as a highly sophisticated mechanical device, a device that is governed by the universal mechanical laws of nature. To highlight this theme, the Renaissance genius’ anatomical sketches are placed in careful, dynamic conversation with his mechanical and geological studies.

Part of the current Da Vinci exhibition in Montepulciano.

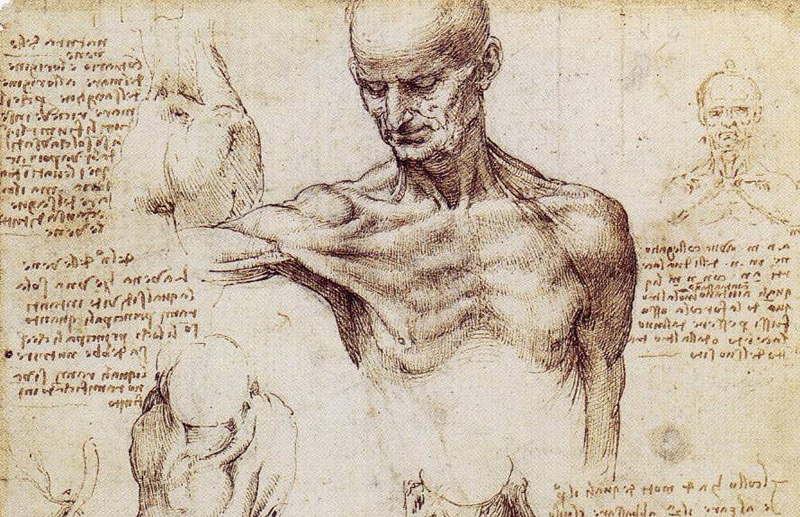

The careful observer of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings might be surprised. While Renaissance art is known more generally for making incredible strides toward realism and Da Vinci is fondly remembered for being a radical genius amongst giants, there are severe limitations in regards to the accuracy of his series of sketches of different systems in the human body. Da Vinci’s quality is always mesmerizing, but you will find the continued influence of the Middle Ages and the overwhelming dominance of the Hellenic philosopher Galen on his work. Galen is notorious for his argument that the body is governed by four humors. If blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm are out of balance, we are sick in body and mind. Although inaccurate, this humoral theory had an inordinate influence on western medicine for more than a millennium and Da Vinci is no exception.

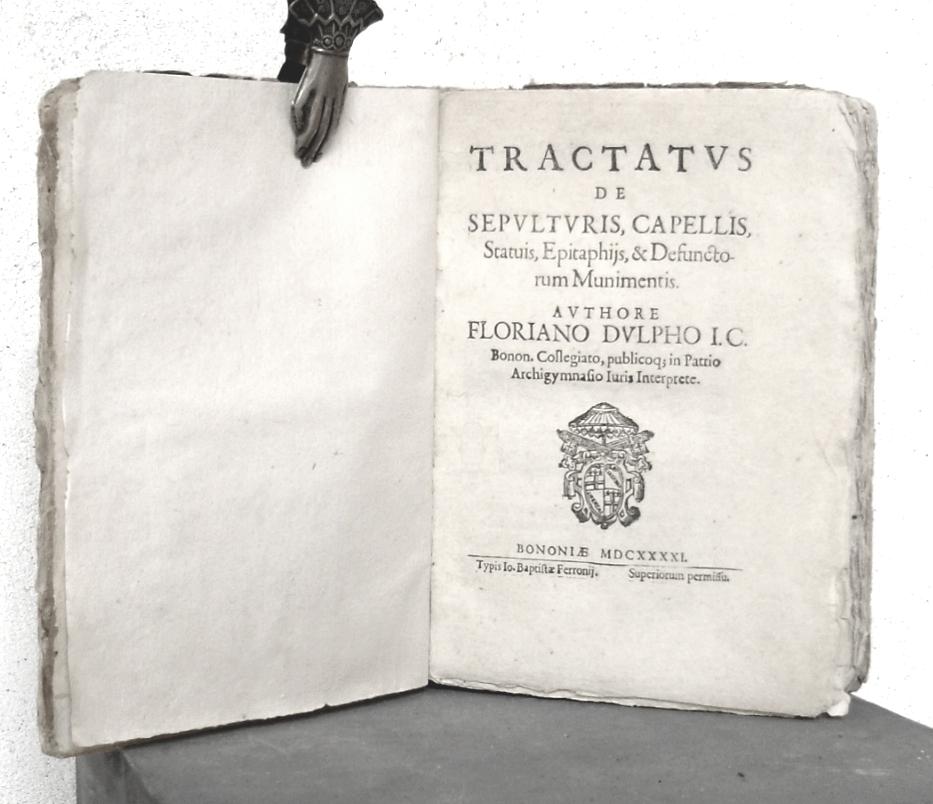

In some part, the continued dominance of Galen into the Renaissance was due to Pope Boniface VIII issuing the bull De Sepulturis in 1300. The papal decree stated that boiling the bones of Crusaders killed in the remote wars was not allowed (something that was being done to make for easier transport home). Boniface argued that the resurrection of the body would have been hampered by this practice, but the bull was interpreted to mean no human dissections were permitted. Da Vinci and other scientists conducted them despite this precedence. By 1405 autopsies were allowed at the University of Bologna, although they were still not commonplace more widely.

De Sepulturis

With limited access to human cadavers, some of which he dissected (or possibly just observed being dissected) at the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, Da Vinci took creative liberty with what he had seen in various animal dissections. He assumed falsely, like Galen, that what was seen in animal bodies mirrored the human body. In the end, Da Vinci created drawings of human organs and systems that were not so much accurate as they were a creative compilation of what he did ascertain from his study of both humans and animal cadavers and his own rather fascinating imagination. Leonardo drew the larynx of a dog, the nervous system of a frog, the placenta of a calf and the heart of an ox in humans. A typical humanist, he looked to classical texts for answers to his questions, but he did not limit himself to past authority, preferring instead to seek knowledge through experimentation.

Anatomical drawing by Leonardo Da Vinci

Less than three decades after Da Vinci’s death, Andreas Vesalius, a professor of surgery at the University of Padua, published De humani corporis fabrica. The anatomical drawings attributed to Vesalius were received as a definitive anatomical text for university use, while Da Vinci’s remained unpublished and fell by the wayside. Vesalius may have heard of Da Vinci’s drawings, but there is no proof that he ever even saw them. Vesalius’ contribution to medicine was immediately recognized. A portrait of him, painted by Titian, in Palazzo Pitti stands as a testament to this.

We do not often think of Da Vinci as playing second fiddle; the idea may even make us uncomfortable. It is also not in vogue to see a father of modern science as a child of the Middle Ages, but his anatomical drawings remind us clearly that he was deeply influenced by the traditions that were passed down from Galen and Aristotle and palatable to the medieval world view.

This exhibit reframes the conceptualization of these sketches and asks us to take another look. “Why do inaccurate anatomical drawings even matter in the digital age?” I wondered, thumbing through dusty copies of Leonardo’s drawings surrounded by future surgeons sitting on laptops looking at accurate 3D models. The answer is that they form a reminder that Da Vinci was a product of his age, just like we are. He was blinded by what he thought was the truth. This exhibit reminds us that even a great mind is imperfectly biased.

Anatomical drawing by Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo’s notes and marginalia speak to his struggle with tradition. Aristotle, Galen and his own move toward experimental science and intellectual independence are at war in these notes. It was the struggle of the humanists more broadly, and it is clear that Da Vinci was pushing his investigations beyond the norm. Artists in the Renaissance were connected to the apothecary guild because of the materials that they needed to make pigment, but he went far beyond the general impulse of artists to study anatomy more deeply.

Yes, Da Vinci was an inaccurate pioneer and protagonist. He thought the larynx was the source of the voice (it’s the vocal cords) and peristalsis contractions, which he knew nothing about, was essential to understanding the mechanics of the digestive system that he explored in depth. The exhibition, focused on mechanics, makes Leonardo’s reliance on animal dissections less problematic when these theories are applied to the mechanics of human systems.

Leonardo the anatomist had a focus on mechanical functionality that pushed the limits of Galen. It is important to consider that the sketches in Montepulciano are notes from initial explorations, not completed studies. The inaccuracies should not overshadow the boldness of Leonardo’s efforts. Rather, they should serve to highlight that his studies were only in their infancy. This exhibition reminds us once again that Leonardo’s greatness is complex and commendable, but not infallible.