“This woman drags the whole of Moscow and the whole of St Petersburg behind her; they don’t just imitate her work, they imitate even her personality.” Praise of that stature is rare for an artist at any time. But these words of Sergei Diaghilev, the great ballet impresario, were spoken in 1913 and they acknowledged the domination of the Russian art world in those years by a woman. Natalia Goncharova challenged conventions and introduced to pre-revolutionary Russia a spirit of creativity that blended traditional folk art and avant-garde modernism. As the latest exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi demonstrates, her vision and energy were astonishing.

Mikhail Larionov (Tiraspol 1881–Fontenay-aux-Roses 1964), Portrait of Natalia Goncharova 1907, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm. Collection of V. Tsarenkov. © Natalia Goncharova, by SIAE 2019

“I set myself no limits in the sense of artistic achievements.” Natalia Goncharova was never content with the status quo. The daughter of impoverished aristocracy from the Russian countryside, she identified with marginalised communities. After all, she was a woman when her gender did not amount to much in society’s eyes. She rebelled against the illusion that, as far as influencing the course of events was concerned, the future was for men.

So she painted the workers she had seen in the fields, such as in Peasants picking apples (1911), and wrestlers in violent combat (probably for money), or Jews who were segregated from their neighbours in cities and only recently subjected to pogroms. Indeed, how she painted these subjects was as controversial as the subjects themselves. Originally trained as a sculptor in Moscow, Goncharova adopted painting as the primary medium of her formative years as an artist. Visiting the homes of the great collectors Shchukin and Morozov (whose palace was open to the public on Sunday mornings in 1908–9), she was exposed to the advanced styles of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso.

Natalia Goncharova, Peasants Picking Apples 1911, oil on canvas, 104.5 x 98 cm. Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, 11955. Transferred from the Museum of Artistic Culture 1927. © Natalia Goncharova, by SIAE 2019

The effect was revelatory. Her work and that of her contemporaries were early converts to the strong, flat colour of neo-impressionism and, later, the bold drawing and compositions of cubism that ignored perspective and natural scale. Goncharova was a pioneer for using all available modern styles and developing them for a Russian context. She also realised the potential of traditional art forms by including among her inspirations the qualities of wood and ancient stone carving, painted trays used in the home, embroidery and popular prints, sources commonly dismissed as “primitive”.

Above all, she translated the sophistication of religious icons into modern symbols. In Cyclist (1913), which also reflects her admiration for Italian futurism, machines are transforming the urban experience and working life for ordinary citizens. Planes and giant looms were the new icons, equally modern and as identifiably Russian as hay cutting and gathering firewood. “The art of my country,” she declared in 1913, “is incomparably deeper than anything known to the West.”

Natalia Goncharova, Cyclist 1913, oil on canvas, 79 x 105 cm. St Petersburg, Petersburg, State Russian Museum, ZHB-1600. © Natalia Goncharova, by SIAE 2019

In Moscow at the time, a generation of artists, poets and musicians was revolting against the cultural stronghold of the West. Her partner, fellow artist Mikhail Larionov, whom she met when both were students at age 20, was fascinated by folklore. He integrated its themes into his painting, which was as radical as Goncharova’s. But the detail that outraged conservative society was that Goncharova was depicting peasants and Jews in formats reserved for Orthodox worship and, as a woman, she was not entitled to paint in the icon style.

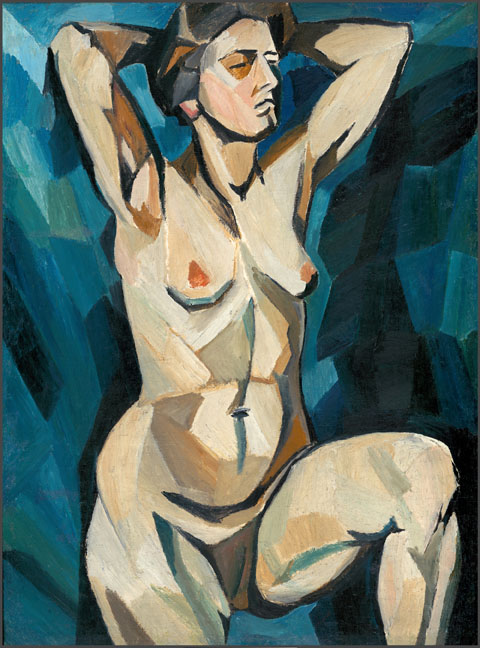

Criticism did not deter her. In 1910, she was arrested for corrupting public morals by exhibiting nudes. At her trial, which was closed to outsiders, she claimed creative freedom, while the lawyers concentrated on her morals and political views. She was acquitted on the technicality that the exhibition had not been in a public place. Nonetheless, perhaps her real offence, in the mind of the Tsarist autocratic rule, was her feminine viewpoint on the nude figure. In A Model (Against a Blue Background) (1909-10), the subject appears defiant: she displays her body to the (male?) viewer, whose gaze she returns with challenging self-assurance. Male painters treated the same subject all the time; it was a staple of the accepted academic tradition. On this occasion, however, the spin of tables being turned was visible.

Natalia Goncharova, A Model (Against a Blue Background) 1909–10, oil on canvas, 111 x 87 cm. Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, ZH-1633. Bequeathed by A.K. Larionova Tomilina, Paris 1989. © Natalia Goncharova, by SIAE 2019

Thereafter, crowds at openings of her exhibitions expected to be scandalized. But Goncharova did not restrict herself to paintings for galleries. She paraded fashionable Moscow streets in 1913 with abstract designs applied to her own face like subverted make-up. Her work included early manifestations of street performance and body art. The press was often present, as she is likely to have alerted the papers herself.

Her behaviour was not directed at building celebrity for its own sake. Goncharova was a genuine innovator who, with contemporaries like Larionov, wanted to break down the obstacles of privilege that kept art out of the reach of wider audiences. She designed book covers, posters, interiors and fashion, and the fluidity and vitality of her vision drew her to the attention of innovative artists in other fields, most notably in theatre and dance.

The costumes for Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera-ballet Le Coq d’Or (1914) cemented her working relationship with Diaghilev and led her to leave Russia for Paris in 1915 with Larionov. She never returned to her native country that would be transformed by revolution in 1917, partly fuelled by the urge for change among intellectuals that she had nurtured.

The different facets of her prodigious output (her 1913 exhibition alone include 731 works) are selectively represented by this Palazzo Strozzi show. It has benefited from numerous loans from Russian state collections and by the clear, uncluttered installation that now distinguishes shows at Florence’s foremost space since Arturo Galansino’s arrival as director in 2015. The galleries stress one important feature: her celebration of colour, absorbed equally from Gauguin and Matisse, and the richly decorated votive paintings of the Church.

Goncharova was an artist ahead of her time. She took on prejudice in art and life, and embraced photography and film in her recognition of the power of imagery. Overlooked in later life but still prolific (she died in Paris in 1962, adored by rich American patrons and fashion houses), her importance is being returned to the forefront of the modern movement. Moreover, she is only the second woman artist to lead a show at this major Italian venue. Another accolade that is long overdue.

Natalia Goncharova. A Woman of the Avant-garde with Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso

Until 12 January, 2020

Palazzo Strozzi, Florence