As the sun beats down on St. Peter’s Square, tourists and pilgrims stand in a long line waiting to enter Vatican City. Souvenir stands filled with a large selection of rosaries and other trinkets surround the imposing square.

“How much?” asks a young Polish pilgrim, pointing at a rosary.

“Five euros,” replies Massimo Di Porto in stilted English. The young woman hesitates.

“Ok, I give you two for five,” offers Di Porto, a bargain. As he walks the streets around the Vatican carrying a tray of crucifixes, papal medallions and rosaries around his neck, most people would never know that Di Porto is a Jew. The only thing that identifies him as such is his last name which means “from the town of Porto.” Many Italian Jewish surnames are really just the names of towns and regions in Italy and Di Porto is one of the most common.

Hawking rosaries and papal gadgets is a Jewish business in Rome and around the Vatican.

Thirty-nine-year-old Di Porto grew up in Rome’s largest Jewish neighborhood, still referred to as “Il Ghetto” because the area once housed the Roman Jewish Ghetto.

Following in the footsteps of his father and his grandfather, Di Porto began selling religious souvenirs in front of St. Peter’s Basilica at the age of 19. He is a sturdy man whose lined and deeply tanned face shows the signs of all the hours he has spent outdoors carrying his tray of keepsakes, working seven days a week, all year round, he says.

Just down the street, Agesilao Di Veroli, 44, has also been selling rosaries and papal key chains alongside plastic models of the colosseum at his souvenir stall for the last 20 years. Like Di Porto, Di Veroli also learned the trade from his grandfather. As a young boy he couldn’t wait until he was old enough to manage his own bancarella, his own stand, he says.

Di Veroli is one of approximately 105 vendors, all of whom are licensed to sell souvenirs at stands in front of Rome’s most important monuments – and all of whom, except for one, are Jewish.

Other ambulant vendors, like Di Porto, carry trays of trinkets but are not licensed to set up stalls. All of these vendors, too, except for one, are Jewish. Like other Italian Jews, some of the vendors are observant, though many are not. Most passersby and many Italians would never know that Di Veroli is Jewish.

“All the vendors know one another. We have grown up together and we help one another out with the business,” says Di Veroli. Nearly half of Italy’s 30,000 Jews live in Rome but, despite its size, the community is extremely cohesive. Like their fellow Roman Jews, the souvenir vendors see each other at weddings and Jewish community events. Their children attend the same schools and their families live in the same neighborhoods.

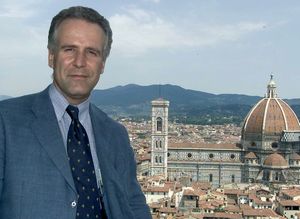

Massimo Misano, 54, took over the souvenir stand once run by his grandmother. For the next few weeks he will sell rosaries and crucifixes alongside ceramic statues of Michelangelo’s David and tiny plastic models of the colosseum in front of the Trevi Fountain. Then he’ll move his stand over to the Vatican. An elegant dresser and a member Rome’s Jewish Community Council, Misano isn’t really concerned about the fact that he sells some traditionally Catholic objects alongside postcards of Rome.

“I believe we provide a service to the tourists who come to the city. We offer them a better price than the stores. We’re part of the folklore and our presence gives energy and color to the city’s squares. Without it, they’d be lifeless,” he says.

Because Rome has been the seat of the Catholic Church for nearly 2,000 years, it is not often associated with Jews. Yet Rome’s Jewish community is the oldest in Europe. Official records suggest that the first Jews arrived in Rome in 168 BCE as part of a diplomatic delegation sent by Judas Maccabeus. Under the rule of Julius Caesar, the Jews were allowed to freely observe their religion and, overall, the community flourished.

But Jewish life in Rome underwent a radical change in 1555 when Pope Paul VI, responding to the threat of Protestantism by cracking down on all forms of heresy, rescinded all privileges enjoyed by the Jews and established a ghetto to isolate them from the Christian population. Jews were forbidden to own shops or property outside the ghetto and were not allowed to practice most professions.

Having little choice in the ghetto, many Roman Jews made their living as ambulant vendors, selling used clothing, fabric and scrap metal. According to Marina Caffiero, a history professor at Rome’s La Sapienza University whose recent book Battesimi forzati. Ebrei, Cristiani e Convertiti nella Roma dei Papi discusses the relationship between the Jewish community and the Papal state. Jewish vendors would also go door to door, buying and selling sacred objects and religious relics. They were allowed to leave the ghetto and walk about the city for the purpose of commerce with a special pass granted by the papal authorities.

Rome’s Jewish community was of great importance to the Papacy.

“The Papal state wanted to keep tight control over the Jewish population, but at the same time the Church needed the Jews, both for economic and theological purposes,” Caffiero explained. “The street sellers provided competition to the Catholic businesses, which had formed monopolies. Theologically, the Jews [were believed to have] witnessed the death of Christ and they represented an important group to convert to Catholicism.”

With Italian Unification in 1870, the Roman ghetto was abolished and the Jews were made equal citizens.

Until the 1920s, selling souvenirs on the streets of Rome required a simple permit. But during the 1930s, as Mussolini’s ties with Hitler grew, so did Italy’s anti-Jewish campaigns. In December of 1938, the Italian Parliament approved the first “Laws for the Defense of the Race,” which forbade Jews from teaching, attending schools and universities, serving in the military or employing non-Jews. The lives of the souvenir vendors became increasingly restricted. No new licenses could be obtained and eventually they were forbidden from practicing their profession.

At the end of World War II, several Jewish families managed to get their licenses back. No new permits have been given out since the war because there is no more public space available to be licensed. So today, the vendors remain Roman Jews and the profession continues to be passed on within the family, with young men usually learning the business from their fathers, as they have done for centuries.