The celebrations of Vespucci Year continue with the

opening of the exhibit at Palazzo Pitti, New Frontier: History and Culture of

the Native Americans from the Collections of The Gilcrease Museum of Tulsa,

Oklahoma. Co-organizer Laura Johnson reflects on the title and gives TF a

personal glimpse behind the scenes.

The exhibition New

Frontier pays tribute to two men of extraordinary vision separated by 450

years: Amerigo Vespucci, who died in 1512, and Thomas Gilcrease, who died in

1962. At the exhibit’s entrance, in the Andito degli Angiolini at Palazzo

Pitti, visitors view on the right a portrait of Amerigo Vespucci (from the

Uffizi’s Vasari Corridor collection), and a portrait of Thomas Gilcrease on the

left. They are connected through their belief in something beyond the horizon,

in the idea of a new frontier.

I was born the year before President John F. Kennedy’s

assassination, so it is impossible for me to remember firsthand his New

Frontier project or the feeling that there was ‘another world’ to discover

through space exploration. Years later when I was studying at the University of

Oklahoma, Norman and the University of Tulsa, I always felt that I was

following the dictum of the American author Horace Greeley, who, in the 1830s,

stated, ‘Go West, young man,’ as I drove the 675 miles (1,110 km) to Tulsa from

my home town of Chicago, where the famed Route 66 starts. It is referred to as

‘The Mother Road’ in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and

commemorated in a song that idealizes the journey to new states or frontiers.

Therefore, when it was decided that the title for the exhibition from the

Gilcrease Museum was to be the New Frontier, I found my mind wandering back to

my more insular viewpoint until I viewed the theme on a grander scale, from a

European’s perspective.

The ‘frontier’ concept suggests a situation that

expands beyond one’s native shores to uncharted territories. Before the

late-fifteenth century, historians had written about the influences of

explorers and the Nuovo Mondo or what could also be called a Nuova

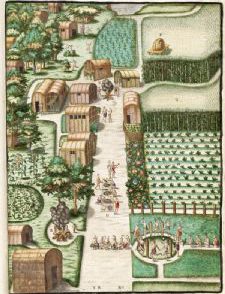

Frontiera. The first room of the exhibition in the Andito degli Angiolini

features artifacts used by the indigenous peoples and landscape paintings of

the unspoiled majesty of uncharted lands of this new frontier. The other five

rooms display pottery, baskets, weavings, and bronzes demonstrating the

customs, religion and way of life of a few of the many tribes of North America.

As the visitor progresses through the exhibit, influences from Europe and the

effects of colonization are clearly noted in how they dressed in European garb

instead of a traditional manner. In the early 1900s,

photographer-anthropologist Edward S. Curtis believed that ‘information is to

be gathered … respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of

mankind.’ American tycoon J.P. Morgan commissioned Curtis to produce a series

on the North American Indians. In order to demonstrate his passion for

truthfully presenting the indigenous peoples, Curtis made over 40,000 images,

of which a selection is on exhibit.

The New Frontier exhibit continues in the Galleria del

Costume on the second floor of Palazzo Pitti and features six rooms with

specific themes, such as the horse, buffalo and children. The highlights

include several dramatic paintings by Frederic Remington, and the beautiful

painting Crucita-Taos Indian Girl in Hopi Wedding Dress and Dried

Flowers by Joseph Henry Sharp. Gilcrease and Sharp knew each other. As

collector and artist respectively, they shared many common interests and both

were concerned with authenticity. Gilcrease even participated in archeological

digs to insure the provenance of the pieces for his museum. Sharp used the

actual items owned by the figures in his paintings, which were then also added

to Gilcrease’s collection. The Galleria del Costume’s Sala di Ballo features

the white boots, colored sash, dress, and ceramic vessel in the still-life

painting.

Thomas Gilcrease may be described as a man with a

passion to preserve and revere Native American cultures. Just like Vespucci,

Gilcrease realized a new frontier, which he simply called ‘a track in life.’ At

the age of nine, Gilcrease, who was one-eighth Muskogee-Creek Indian on his

mother’s side, was granted 160 acres (68 hectares) of land just south of Tulsa

through the 1899 Dawes Commission allotment process. By his early twenties, he

had become a multimillionaire when this seemingly unproductive plot of land

gushed forth the black gold of oil and he continued to buy other oil-rich land

tracks. Like most youth, Gilcrease was restless and wanted to discover the

world beyond his homeland. His travels took him to all parts of the world,

always with an interest in learning about different cultures and educating

himself by reading voraciously. He mastered French and Spanish and was

especially interested in geology.

Because of his frequent visits to the great museums of

Europe, and realizing that there were no great museums in the United States

that specifically addressed the history of Native Americans, Gilcrease was

inspired to establish one. In 1943, he opened his first museum and by 1949 he

had built one near his home in Tulsa, where the museum is still today, now with

a collection featuring 100,000 rare books, maps and documents as well as more

than 250,000 artifacts. The Gilcrease Museum is owned by the City of Tulsa,

which has partnered with the University of Tulsa to steward the museum and its

collection.

In Gilcrease’s memoirs, we note how warmly he embraced

Italy. He speaks of walking its cobblestoned streets and admiring the

antiquities of Rome, the monuments of Florence, and the canals of Venice. His

lifelong motto was ‘every man must leave a track and it might as well be a good

one.’ We should imagine this exhibit as part of that track.

Perhaps on this, the 50th anniversary of Gilcrease’s

death, we can say that a full circle has been made. An unforeseen consequence of

his vision has been achieved with the New Frontier exhibition of Native

American art in Florence during the quincentennial year of Amerigo Vespucci,

the man who gave his name to the new frontier known as America.

New Frontier: History

and Culture of the Native Americans

From the Collections

of The Gilcrease Museum of Tulsa, Oklahoma

Palazzo Pitti – Until

December 9, 2012, www.unannoadarte.it