Knocking up a nun and running from the law isn’t a bad way to end your career as a monk. Filippo Lippi lived and worked with a fierce passion. While his lust for life and love are legendary, the restoration of his frescoes at the Duomo of Prato show him to be nothing short of concrete genius.

Filippo Lippi, or Fra Lippi, was born in Florence in 1406. At a young age he joined the Carmelite friars at Santa Maria del Carmine of Florence, home of the Brancacci Chapel and Masaccio’s frescoes. He showed an interest in drawing and painting from a very early age and was encouraged to become an artist. Although he was permitted to leave the monastery in order to work, he was forbidden to leave the order.

As a monk, his insatiable appetite for sex was far more worrying than his interest in the arts. Lippi’s lust for life was so great and distracting that Cosimo de’ Medici found it necessary to lock him in the studio so that he would finish his work. Money spent on prostitutes and other amorous expenses left Lippi broke and constantly seeking commissions.

In 1453, another Florentine monk, Fra Angelico turned down the commission to paint the Duomo at Prato. The work was offered to and accepted by Lippi, and he relocated from Florence to undertake the assignment. It was in Prato that Lippi, then 50 years old, encountered Lucrezia Buti. He immediately fell in love with the beautiful young Florentine nun. He convinced the mother superior of Santa Margherita to allow Lucrezia to model as the Virgin Mary for another commission he was painting. He then abducted her and refused to return her to the convent. What followed was a 30-year relationship, allowed to continue thanks to the pope’s dissolution of their religious vows. They had two children together. His son, Filippino Lippi, would become a great painter in his own right.

Romance, abduction, children and other commissions meant the painting of the chapel took 13 years to complete. The two walls depict the cycles, or lives, of two saints. Saint Stephen’s story begins with the swapping of a baby with a demon who is then abandoned on a river. Later Stephen is called upon to expel the demon, and we see a ghostly figure ascending from the boy’s head. Around the corner, Stephen is mocked by a crowd as he delivers a sermon and is eventually stoned to death. In the final section of the cycle we see the funeral of Stephen and Christ receiving him in heaven.

This painting uses a wealth of pioneering techniques. The perspective Lippi incorporated in this picture was new and allowed a fluency of pictorial storytelling never seen before. Interiors cut away to exteriors that recede into the distance, allowing scenes to take place chronologically within the same plane. Floors of cathedrals and palaces, painted in one-point perspective, draw you into the picture. The different handling of figures and environment create an illusion like that of a pop-up book and pull the eye to the most important elements of a scene.

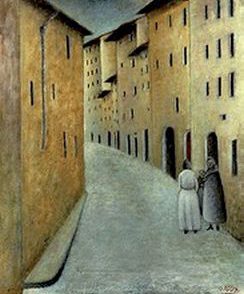

The opposite wall depicts the life of Saint John the Baptist. His early life is depicted in the lunette as he leaves his family to begin preaching in the desert. The ‘desert’ he arrives in is an amazing blue moonscape full of caves, arches and stairwells. So bizarre is his rendering that one is tempted to assume that Lippi had never seen a landscape outside of Tuscany. However, accounts of his abduction, sometime between 1431 to 1437, by Moors to the Barbary coast in suggest that he was familiar with desert landscapes. Thus, the orange-robed characters in the cold, blue-grey desert landscape result from his memory.

The magnum opus of the cycle is the dance of Salome. The setting is a crowded banquet hall. The elegant floating figure of Salome (Lucrezia Buti) dances across the multicolored geometric inlaid floor. The scene is so beautiful, with great depth, unified tone and juxtaposition of harsh perspective against such sensuous curves and movement, that it seems impossible that a man is being beheaded on the left-hand side of the picture. Witnesses stifle their expressions of disgust as Salome presents the head of Saint John the Baptist to her mother, Herodias, who receives it with placid indifference. Fighting curiosity, a woman on the far right of the painting turns her head away from the scene yet steals a glance of the horror unfolding. The result is a chilling outward gaze that meets the viewer head-on.

Lippi would never reach these heights again. He completed the frescos at Prato in 1465 and accepted a commission in Spoleto, where he died before completing the work. He was 63 years old.

Crucial to the development of Renaissance painting, both Michelangelo Buonarotti and Leonardo da Vinci studied Lippi’s frescoes. Sandro Botticelli (1444-1510) was one of his apprentices and owes much of his style to Lippi. The dancing figure of Salome, with her great, flowing contours, clearly made an impact on the young Botticelli.

The restoration of Filippo Lippi’s masterpiece has taken five years to complete. Now we can clearly see his work in the vivid intensity he intended. Mesmerizing: the inventive perspective, expressive brush strokes and pictographic storytelling appear far more powerful than realistic. When compared with the nineteenth-century academic realist frescoes in the chapel next door, it is clear that passion usurps technique.

Filippo Lippi: Genio e Passione (permanent exhibition)

Duomo of Prato, Prato

Hours: Monday to Saturday 10 to 5; Sunday 1 to 5

Entry: 3 euro; audio tour .50; free for children under 10

Call centre: APT Prato 0574 24112

Guided tours available in English, French, Spanish, German and Russian:

Thursday 3:30, 4:30, Saturday 10, 11, 3:30, 4:30, Sunday 3:30, 4:30, 5:30

Cost: 5 euro per person, includes reservation and entrance into the two chapels with guide

4 euro per student in school groups; free for students under 10