…Count

Nicola of Pitigliano [Orsini] had sexually

assaulted his own daughter-in-law, wife of the

Count’s son, Alessandro … and the family of the woman were planning to go to

Pitigliano and take her back home. Moreover, Count Nicola just had a son, after

three daughters, by his Jewish lover and has made a great feast of it, which

was a big blow to Alessandro and his mother … (Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Mediceo

del Principato 1872 – February 1560)

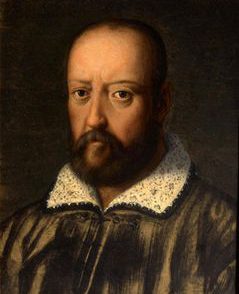

Federico Barbolani da Montauto, then governor of Siena, sent this letter

to the Florentine court. At the time of the missive,

Siena had been under Florentine control for five years, annexed in 1555 after a

long and devastating war that left many scars on the urban and rural

populations. The Sienese had been extremely recalcitrant in

accepting Cosimo I de’ Medici’s rule. Exacerbating the situation, Spanish

(pro-Florence) and French (pro-Siena) troops were stationed in and around the

walls of Siena. Not surprisingly, the Duke wanted a daily update, particularly

information about dissent or social unrest.

Barbolani da Montauto’s charge to govern Siena was,

thus, a challenging one. Yet as this passage indicates, one family in

particular added to the governor’s burdensome task.

Pitigliano is in the Maremma territory, on the

southeastern borders of the ancient Sienese state, close to the former papal

territories. The Orsini family had ruled over this town since the thirteenth

century. Count Nicola, who also served as high officer in the Florentine army,

was a notoriously treacherous and violent man.

The count had married Livia in 1533, and

Alessandro was their son. Marriages, especially among the nobility, were

usually for economic, social and political benefit, but there were unspoken

rules of behavior. Although noblemen’s relationships with servants or

concubines were condoned, flaunting such a relationship, as the feast to

celebrate his illegitimate son’s birth would suggest Nicola did, was not.

(Their wives, on the other hand, risked serious consequences should they be

caught with their lovers).

Moreover, religious mores of the time precluded

Nicola’s relationship with a non-Christian. Nicola’s lover was probably a

former servant of the Orsini family, and most likely, she was a member of the

vast Jewish community that populated Pitigliano in the sixteenth century.

As governor, Barbolani da Montauto was faced with

two serious issues. He had to address Count Nicola’s crime: if proven guilty in

raping his daughter-in-law, the count could be condemned to death or to the

galleys, according to a particularly severe law, issued in December 1558,

against violent crimes, especially those of a sexual nature. He also had to

address Nicola’s defiance of religious mores although Nicola claimed publicly

that she had renounced her faith and had become a Christian).

Still other laws affected this family. As son and

husband, Alessandro had the burden of defending the honor of two women, his

mother and his wife, but he was legally under his father’s power.

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, women and

children were under the potestas (legally speaking, the authority) of

their father (or their brother, if the father was dead); and married women were

under the potestas of their husband.

The children, whether male or female, were under

the potestas of the father until his death. In a custom that went back

to ancient Roman law, sons and daughters were not free from the father’s potestas not even when they became of age, usually at 25 years. It took a legal act, emancipatio,

to make a child, even an adult child, legally and economically independent from

its father.

For Alessandro’s wife, the potestas was a

benefit. Her family was planning to go to Pitigliano to rescue her, thus honoring

their duty to protect and defend a family member.

As for Alessandro? We learn in a report from the

Venetian ambassador, where Nicola is described as a despicable man, that

Alessandro asked Cosimo I to help assassinate his father.

When Nicola learned of this plot and of

Alessandro’s intentions to take over Pitigliano, he immediately imprisoned his

son.