Some like it cold

So, you think that ice-cold drinks are a modern American invention? Well, here’s news for you: frosty beverages were the rage in Italy centuries before America was discovered. They became especially popular in Renaissance Florence.

French essayist Michel de Montaigne, who traveled through Italy in 1580-1581, kept a journal to record his impressions of the places and people. He took the greatest delight in describing the odd behaviour of foreigners. What struck him as particularly odd about the Florentines was that ‘They have the habit of putting snow in their glasses of wine.’

People living in a hot climate like that of Italy must have sipped cool drinks since time immemorial. Ancient Roman writers wrote about chilled beverages, and we can easily imagine Pliny the Younger, back in the first century A.D., downing many an icey drink in the garden of his beloved villa near Tifernum (now Città di Castello). Boccaccio routinely provided the Florentine ladies and gentlemen in his fourteenth-century tale, Decameron, with ‘the coolest of wines’ to slake their thirst at the end of a stifling summer’s day.

Since cellars, wells and caves were the refrigerators of once-upon-a-time, the traditional way to chill wine was to repose it in one of these places several hours prior to serving. Then one day, around the same time that Montaigne visited Italy, someone happened to come up with a very clever idea. Bernardo Buontalenti, the Medici’s favourite engineer-architect, had figured out how to preserve ice and snow during the hot summer months. As a reward, he was offered the potentially lucrative privilege of selling it. However, the privilege was burdened with so many obligations that he decided to pass it up.

Buontalenti’s discovery did not stay a secret for long. By the next century, Florentines regularly collected ice during the wintertime, depositing it in deep pits to use over the summer for chilling not only wine, but also water, fruit and lots of other things. When the winters in the valley were too mild for snow, they hauled it down from the mountains. The practice of chilling wine with ice became so entrenched that it figured in a seventeenth-century treatise of Florentine customs, under the rubric ‘Cool drinks,’ alongside such topics as weddings, funerals and baptisms.

As can be expected, the Medici Grand Dukes boasted one of the largest and most efficient ‘refrigerators’ in all of Renaissance Florence-a proper ice-house, installed in a hillside in the Boboli gardens, beneath which was a grotto for the storage of wines. The methods of chilling wine in the grotto were two: bottles of wine were placed inside large containers and ice packed around the bottles, or the wine was poured into large glass flasks equipped with a cavity at the center for holding ice.

Not much time passed before someone designed a cup in which the beverage could be chilled directly. Very likely it was a cup of this kind that Montaigne saw when he commented on the Florentine habit of combining wine and snow. From surviving drawings, we know that the designs for these cups ranged from utilitarian to fanciful. The most elaborate cups were similar in appearance to some of the rock crystal vessels on display in the Museo degli Argenti, although there is nothing in that collection identifiable specifically as a ‘cooler cup.’

The technique for chilling wine directly in the cup was as simple as it was ingenious. The ‘cooler cup,’ shaped more like a shallow, oval bowl or sauceboat than a round cup, was made of two shells-the lower, outside shell held the snow or crushed ice, the inner shell the beverage. The designs were sometimes very extravagant and could turn the drinking of wine into a proper ceremony. One such cup, for example, had a small bottle attached to its rim along one of the short oval ends. The bottle contained the wine, which was released into the inner shell of the cup by way of a pipe. The flow of wine could be regulated by opening or closing a valve, so that it either trickled in slowly or spurted like a small fountain. To drink, one held the cup in both hands and tipped the other short end into the mouth.

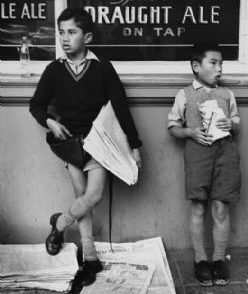

Before long, botteghe in the fashionable part of Florence started offering their customers wine in icy carafes. Here, to all intents and purposes, we have the forerunners of today’s elegant bars. Wine wasn’t the only chilled beverage they served: there was also water flavoured with a whole range of spices or essences, such as jasmine, lemon, and cinnamon, to name only a few. The next time you find yourself in a bar like Rivoire, open your mind’s eye and picture the room filled with dandies dressed in silks and satins, gossiping about the latest scandals at the granducal court while sipping a refreshing jasmine-flavoured aqua minerale.