Filmmaker David Battistella moved to Florence from Canada in 2011 to pursue his dream: writing and producing a feature film based on Ross King’s 2000 book Brunelleschi’s Dome, about the life of Filippo Brunelleschi and the building of Florence’s Cupola. This column, which began with TF 149, chronicles Battistella’s pursuit of his dream, including anecdotes of his new life in Florence and his efforts to finance and launch his ambitious project. He also shares his experience of being a ‘reverse immigrant,’ an Italian born abroad who returns to an Italy that is vastly different from the one his parents left in the 1950s.

My research on Filippo Brunelleschi led me to want to discover what the diet was in fourteenth-century Florence.

Now, in Italy, at some point the conversation almost always turns to food, and this conversation would be no different. For food is a revered and unifying force for Italians, and there is no shortage of opinion or discussion: tastes are particular, and seasonal foods and cooking methods are tried and true.

My search for Brunelleschi’s lunch had taken me to a well-known Florentine historian, whose family’s roots are in the fine art found in Italian kitchens. Luciano Artusi and his son Riccardo have a very famous Italian surname. Their grandfather’s brother was Pellegrino Artusi, whose cookbook is a staple in Italian pantries (see TF 58 and food feature this issue), and whose recipes are written with such precise amounts as ‘a handful’ or ‘as you see fit.’

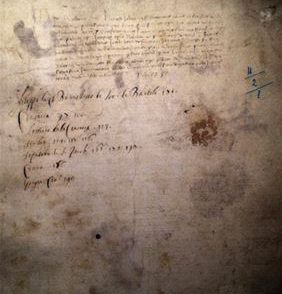

I quickly discovered that Luciano Artusi has written over 70 books about Florence’s folklore and history. He is also the past and honorary president of the Calcio Storico Fiorentino. But when I first contacted him about diet in the fourteenth century, he had a little surprise for me: a private tour of Palagio di Parte Guelfa and a peek at one of Filippo Brunelleschi’s early commissions for the silk guild, where he apprenticed as a goldsmith.

The rooms in this palazzo are filled with history, but one commands special attention. Its ceiling is completely adorned in silk the deep red of a fine Chianti wine, with strands of gold thread running through a pattern of gigli, lilies, the symbol of Florence. The sight left me open-mouthed as I imagined the creativity and effort that went into swathing the ceiling of the city’s finest rooms in opulent silk.

Mr. Artusi then showed me into his former office in the palazzo, whose entry holds a rare gem: a set of bronze doors attributed to Lorenzo Ghiberti, Fillippo’s rival at the time, decorated by marble columns carved by Donatello. I thought about having that space as an office. Not many people go to and from their desks by way of doors made by two of the greatest masters of the Italian Renaissance.

Finally, my host was ready to discuss food in Brunelleschi’s day. He explained that within the city’s walls were gardens that could sustain citizens when, for one reason or another, the city’s doors needed to be locked. Very little meat was consumed and the diet consisted principally of legumes and vegetables. (By the way, no tomatoes: they had not yet arrived in Italy.)

The winter staple was grains. Bread was baked throughout the city, and the main storage for grain was the top floor of Orsanmichele. Common people used wooden utensils to eat their meals. Wine, because fermented, was filling and nutritious in small quantities.

Perhaps this diet is the reason Brunelleschi lived to the ripe, old age of 69. It must have been the good food grown within the city walls.