The Cupola is a marvel. An eight-sided marvel. As round as it looks from a distance, up close we can observe that it was built on an octagonal base. Its eight sides are referred to as ‘veils’ or in Italian, vele, like the sails of a ship. It is interesting that such a great mass of rock, limestone, mortar and iron was given such a light and lofty nickname when referring to its parts.

The Cupola did not become an eight-sided structure by accident. The ancients believed that the number eight carries with it both mathematical and biblical powers. The eighth day is said to be the day of the Lord, so the religious buildings followed a mathematical structure that would honor the days of the week and leave room for God.

The Cupola is also a mirror of another famous building in Florence, one that predates the Cupola by at least 400 years: the Battistero di San Giovanni, the smaller, Romanesque eight-sided structure, also in piazza del Duomo. This building features a majestic mosaic ceiling and is said to have been the site of a Roman domus.

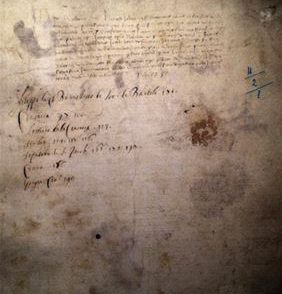

Documents from the year 897 CE prove a building has been standing in that same spot for at least 1100 years. It is still a working church and serves as the official baptistery of the city of Florence. (One can view the records of baptisms in Florence at the archive of the Opera del Duomo from 1450 on.)

For Filippo Brunelleschi and his predecessors, the task of erecting a cupola provided a challenge: it meant building to a specific standard while maintaining rites and rituals laid down before them. The scale is much larger than that of the Baptistery. In fact, the altar that stands under the Cupola today carries the exact same dimensions of the inner walls of the Baptistery. Indeed, visiting the Baptistery first, then the cathedral, would be quite an impressive way to appreciate just how vast the Cupola is.

The walls are five meters thick and arch upward to a height of 66 meters. That is the height where Brunelleschi’s work began. He would have to manage the curves and arches of this eight-veiled structure and have them meet at a point some 90 meters above the ground at the center of the church’s crossing-point.

The Baptistery, so central to Florentine life, was named for Saint John the Baptist, the city’s patron saint. It is said that at one moment in history, when Florence had a particular advantage over Rome, a deal was struck to have the remains of the head of John the Baptist purchased from the Vatican and brought to the city of Florence.

The deal was set and the plan put in place to transfer funds and exchange the remains. Legend has it that a small group of Romans caught wind of the plan and moved the remains before the pope could recover and sell them to Florentine interests.

It is just one example of how divided-or proud-cities remain, even within the larger structure of the over 150-year-old country known as Italy. One cannot help but begin to understand why Rome is Rome, Florence is Florence and Pisa is … well, let’s leave it at that.

Filmmaker David Battistella moved to Florence from Canada in 2011 to pursue his dream: writing and producing a feature film based on Ross King’s 2000 book Brunelleschi’s Dome, about the life of Filippo Brunelleschi and the building of Florence’s Cupola. This column, which began with TF 149, chronicles Battistella’s pursuit of his dream, including anecdotes of his new life in Florence and his efforts to finance and launch his ambitious project.