With the unification of Italy, the Basilica of Santa Croce became known as the Pantheon of Italian Glories, where the country’s most illustrious personalities would find their final resting place. Many marble tombs to prominent women—from princesses to art patrons and artists—still grace the complex, though their stories have often slipped into oblivion. My hope is that a new book, Santa Croce in Pink: Untold Stories of Women and their Monuments, which I co-authored with Giulia Bagioli, Donata Grossoni and Paola Vojnovic, will bring attention to those stories. In the meantime, to get you started on a visit, I spotlight a handful of Santa Croce’s monuments to women.

Let’s start inside the basilica, at three particular tombs.

Charlotte Bonaparte, the French princess, died in 1839 while fleeing Tuscany to cover up an illegitimate pregnancy. Her marble tomb, sculpted by nineteenth-century Florentine master Lorenzo Bartolini, is in the Giugni Chapel. This simple monument was commissioned by the princess’s mother, Julie Clary—whose own sepulcher stands just a few feet away. ‘Worthy of her name’ is the funeral inscription Clary created for her daughter, who was deeply admired by liberal contemporaries who frequented her lively salon in Florence’s Palazzo Serristori. Poet Giacomo Leopardi described Napoleon’s niece as a woman ‘made to enchant spirits and hearts’.

Lorenzo Bartolini also created the funeral monument for Zofia Czartoryskick Zamoyska, one of several Polish aristocrats whose remains are interred in the church. Considered one of the loveliest women in Europe in her day, she was the daughter of Countess Izabela Flemming, a well-known patron of the arts who founded the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków, Poland’s first fine arts museum. Near this interesting tomb, which combines Renaissance-inspired religious imagery and realism, visitors can also see a mixed-medium monument to another Polish princess, Sophia Kickick Cieszkowska; its bronze portal, cast in 1873, was awarded a prize at Vienna’s World Fair.

Galileo’s beloved daughter Virginia Gamba entered the convent of San Matteo at age 13 and adopted the name Maria Celeste to honor the Madonna and commemorate her father’s love of astronomy. The revolutionary scientist would describe his daughter as a woman of ‘exquisite mind and singular goodness.’ Suor Maria Celeste also acted as the convent’s apothecary and prepared medicines for her exiled father’s ailments. The pair exchanged ample correspondence, including 124 of her letters discovered among Galileo’s papers after his death in 1623. The female corpse discovered in Galileo’s original tomb (in the basilica’s Medici chapel) is thought to have belonged to Suor Maria Celeste. It was moved to a new position under the central nave when Galileo’s monumental tomb was created in 1737.

Santa Croce’s Gallery of Nineteenth-Century Monuments contains several memorials to women. But just before stepping into the gallery itself, look to the right of the courtyard’s entrance, where you’ll find a lovely memorial to Florence Nightingale. Named for the city in which she was born, Nightingale is considered the founder of modern nursing. Her multi-decade battle for health-care reform began with her efforts in the war fields of Crimea. This simple monument in Carrara marble and pietra serena was created in 1913 by English sculptor Francis William Sargant. It depicts Nightingale as the ‘Lady with the Lamp’ and inspired the poem Santa Filomena penned by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow after hearing reports about Nightingale’s first revolutionary mission.

In 1792, the poet Fortunata Sulgher Fantastici was immortalized in Angelica Kauffman’s portrait of her, now in storage at the Uffizi Gallery. Accepted to the Accademia dell’Arcadia at the age of 15, Fantastici played a fundamental role in promoting Italian improvisational poetry, a genre that blossomed in the late eighteenth century. Poets composed long, off-the-cuff verses and performed them in key literary salons throughout the peninsula. Finding Fantastici’s slab tomb on the floor of the Gallery of Nineteenth-Century Monuments is a bit of a challenge: look for it near Ida Botti Scifoni’s marble bust, at the far end of the galleria, on the right-hand side.

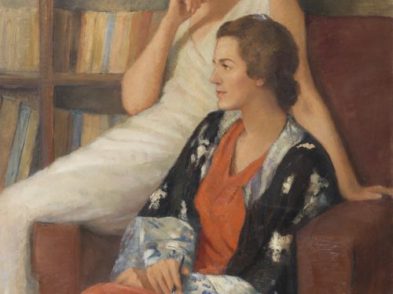

In 1848, princess and art patron Mathilde Bonaparte commissioned Pietro Freccia to sculpt this noteworthy bust honoring artist Ida Botti Scifoni. Princess Mathilde’s dear friend and teacher, Botti Scifoni, had worked as her personal stylist and designer, using her talents to enhance the opulent Villa San Donato in Polverosa, where the princess lived in the early 1840s with her ill-matched husband, Russian magnate Anatoly Demidoff. While viewing the work, take a close look at Botti Scifoni’s sculpted brooch; this tiny painter’s palette emphasizes her standing as a professional painter. Botti Scifoni is remembered as a masterful portraitist and her oil-on-canvas self-portrait is on view in Pitti’s Modern Art Gallery, in the same room that fittingly displays several depictions of her royal patron.

Lorenzo Bartolini’s stellar pupil Luigi Pampaloni fashioned his tomb for opera singer Virginia de Blasis in the late 1830s. The Florentine sculptor depicts de Blasis in the act of performing Vincenzo Bellini’s Beatrice di Tenda, the last opera in which she appeared during concurrent performances at La Pergola and Del Cocomero theaters during 1837. Take a long look at the wonderfully detailed sheets of music lying at de Blasis’s feet. Equally moving is the inscription at the base of her tomb, taken from Beatrice’s aria in Act 2: ‘If an urn is granted to me, don’t leave it without a flower.’

JOIN US for a book presentation and guided visit of several monuments at Santa Croce!

Santa Croce in Pink: Untold Stories of Women and their Monuments

Sala del Cenacolo, Santa Croce Complex, piazza Santa Croce 16

Thursday, October 10, 5.30pm

Event organizers: Opera di Santa Croce and Advancing Women Artists Foundation

Admission is free.