If religion has given birth to all that is essential in society, it is because the idea of society is the soul of religion.-Émile Durkheim

Experiencing Florence includes far more than a discovery of its artistic treasures: it is also a discovery of self and others. This is the conclusion of Larry Basirico, professor of sociology, former chair of the department of sociology and anthropology and former dean of international programs at Elon University. In a series that started in the TF198 digital edition, Basirico, who has authored articles about identity and the family as well as introductory sociology textbooks, reflects on what he observed while living in Florence in the fall of 2013 while serving as visiting professor at Accademia Europea di Firenze. See the most recent in TF202 digital edition.

While in Florence, my family and I lived in a lovely apartment not 50 meters from the northwest corner of piazza della Signoria. Early each morning, before the distracting hum of tourists began, a choir of church bells would hauntingly reverberate through the city, their sound hovering like angels, welcoming the day. On Sunday mornings, very early, before Florence woke up, I would walk through the piazza towards the Uffizi and down to the Arno. The experience of enjoying the solitude of the occasional rowers and hearing the church bells while staring up towards piazzale Michelangelo and glimpsing San Miniato al Monte, then turning around and catching the rooftop of the Duomo was nothing less than mystical.

Our via dei Calzaiuoli apartment was on the second floor, 54 steps up. We trekked up and down the steps 5 to 10 times every day, on our way to school, work, shopping, for dinner, gelato, a cup of coffee, or a quick trip to the fruit stand. Each time we walked down the steps we encountered a mini-shrine of the Blessed Mother on the wall of the first platform of the stairwell. Beneath the shrine is a plaque inscribed boldly: Chi saluta questa immagine recitando un Ave Maria acquisterá 300 giorni d’indulgenza (Whomever greets this image reciting one Hail Mary will acquire 300 days of indulgence).

To those uninitiated to Catholicism, this means that for every recitation of the Hail Mary, 300 days would be subtracted from the time spent languishing in Purgatory awaiting entry into Heaven. The placement of the image and message, in a high-traffic part of a residence, suggests that each passerby would understand its significance.

As any visitor or resident knows, religious images of this sort are seemingly everywhere in Florence. Frescoes, reliefs, paintings and statues with Christian—specifically Catholic—themes decorate the walls of buildings throughout the city. As Lettie Heywood wrote in ‘Street Shrines’ in The Florentine, ‘Glance up and it is likely that you will chance upon one of the 1,200 tabernacles that adorn even the most decrepit and mundane of buildings; these sometimes primitive pieces of art that dot the city, often behind a gauzy veil of dirty glass, are a testament to the once fervent religious nature and atmosphere of the town. They are a constant reminder that although the origins of the city are pre-Christian, Florence was dedicated to the Virgin Mary … The omnipresent images in tabernacles-on houses, shops and street corners-served to promote devoutness as a constant reminder of “truth” as decreed by the Catholic Church’ (see theflr.net/streetshrines).

As secularized as Florence has become, the ubiquitous Christian imagery plays a significant part in shaping its collective consciousness. In his book The Division of Labor in Society (1893), French sociologist Émile Durkheim defined collective consciousness, one of the central concepts underlying most of his writings, as ‘the totality of beliefs and sentiments common to the average members of society.’

Religion, in Durkheim’s view, should be considered primarily from the point of view of how it represents, and how it is shaped by, societal values rather than a spiritual force and, in turn, its effects on people within society. Religion serves as a source of social solidarity by providing meaning and affirmation for the norms, morals and beliefs of groups of people. It pulls people together psychologically as well as physically through its congregational practices, symbols and structures. As such, it becomes a central part of the collective consciousness of people within a society. For Durkheim, religion is important not so much for its spiritual relevance but for its importance as a source of social cohesion.

The collective consciousness that stems from a Christianity of a particular time saturates Florentine culture: the essence of Christianity is an inescapable element of the reality of Florence. Florence is not unique in the Western world as having a presence of religion as a powerful force, but it may be unique in the concentration of Christian references. For example, Florence has approximately 140 churches within 40 square miles (102 square kilometers) contained within the fourteenth-century outer city walls. That is nearly one church per quarter square mile.

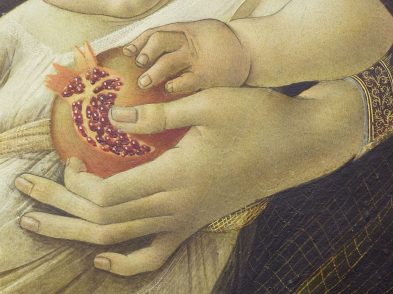

Whether one is looking at Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise doors at the Baptistery: Donatello’s relief sculptures on the outer walls of Orsanmichele: any of the multitude of iterations of paintings of the Madonna and Child in the Uffizi, the Accademia gallery or in churches; or the Christian imagery of the city’s tabernacles, there is no denying that a collective consciousness of Christianity still permeates Florentine life and is essential to maintaining the life and history of the city.