Editor’s note: It is with great pleasure that The Florentine publishes the winner of the 2015 Short Story Contest.

Organized with The Sigh Press, we received more than 60 entries from as far afield as Washington, Los Angeles and the south of France. Themes ranged from religion to love, from everyday life to beauty.

Our guest judge Kamin Mohammedi praised ‘The Letter’ as ‘a mature work. Well written and different, the story is communicated well. I enjoyed its clear style and succinctness.’

‘Firefly City’ by Kelsey Clifton placed second, a love story centred on Florence and two students who may (or may not) be embarking on their own romantic adventure. Read Kelsey’s story in the digital edition of this issue of The Florentine.We thank all of our participants, The Sigh Press (Lyall Harris and Mundy Walsh) and Kamin Mohammedi as well as Todo Modo bookshop for hosting the Short Story Night on May 12 and La Cucina del Garga for generously offering prizes.

The Letterby Oonagh Stransky

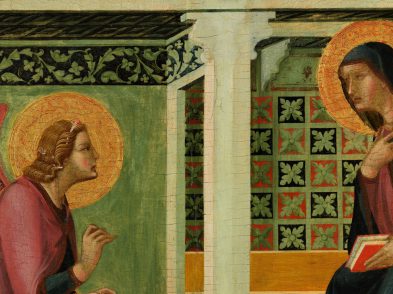

illux by Leo Cardini

She had a ridiculous task in front of her. She had to write a letter to the local Conte, announcing her presence and making a request that only he could fulfill. It seemed like such a nineteenth-century thing to do and she felt it was rather humiliating. But she would do it. Writing the letter would make her feel a little less invisible, help her stake her claim.

Not that invisibility was a bad thing. In New York City, where she had lived for the past fifteen years, she had enjoyed being simply spectral, just another person with a deep inner life, working at having it recognized and affirmed. But the time for that was over. She had moved to the countryside near Florence to maintain clarity and impulse. There were fewer distractions here and she needed to work.

How frivolous, she thought again, to have to write a letter to a Conte. But at the same time, she liked struggling with the wording. She didn’t know how she would approach him—if she should be direct and very American, or coy and ingratiating, or all of these things at once. A friend who knew about these things, someone who relished aristocratic traditions, probably because he secretly wished he belonged to that caste, told her that she should address the Conte with his proper title, N.U., an abbreviation for Nobil Uomo, followed by his complete, and very long, surname.

“Mi presento a Lei con molto rispetto, un pizzico di imbarazzo e sopratutto con il desiderio di…”

That was how she would start. She would step right up to the plate and make her request, which was really an offer of help, but which for her represented an opportunity to do what she loved most: ride people’s horses. That the Conte was both a significant landholder and equestrian was too much of a cliché. No, she wouldn’t write the letter. It was pathetic. Pathetic to think that these kinds of people still need to be addressed in a certain manner. Pathetic to think that she had to grovel. Pathetic that she enjoyed it.

It reminded her of another letter she had struggled to write in Italian twenty years earlier. At the time she had been living in an apartment near Le Cure in Florence, studying manuscripts at the Universita’ di Firenze. Her roommates were two other American girls, although both of them were of Italian origin: Paola Salvatore and Enza Caporaso. Their apartment didn’t have a washing machine, there were no laundromats, and so the girls washed their clothes in the bathtub. If it were raining, they’d hang them all over the house to dry: clothes draped on chairs, radiators and desks. If it were clear outside, they’d hang them on the laundry line from their balcony, which looked onto an inner courtyard and other people’s balconies. Sometimes they would forget the clothes out there and they’d freeze. Sometimes they never dried and just got mildewy. One day, she and Enza realized that they hadn’t pinned their clothes to the line very well—maybe they had pinned too many together—because a few pairs of their underwear had fallen to the balcony of the apartment below. They could see their panties lying on the floor, exposed, unladylike, vulgar. They decided to draft a letter, place it in the laundry pin basket and lower it down to their neighbor, hoping she would read the note and return their panties in the basket.

They worked on the note for a whole afternoon. It was difficult and hilarious; they tried to find the words to express their embarrassment and shame, while still being grammatically correct and polite.

“Cara signora, abbiamo perso le nostre mutande…”

They laughed about their awkwardness, composing draft after draft in a notebook. It made her smile to think of their mistakes and botched attempts, their camaraderie and heartiness. After college, she had packed that notebook and its drafts away in a trunk and stored it at her grandmother’s house in New Jersey. When her grandmother died, she had to go through it. She had decided to throw it away, and erased a part of herself. Now she wished she had it. She would have gotten inspiration from their missive to the casalinga downstairs for her silly letter to the Conte.

She thought about Enza and grinned at the memory of their adventures. They had spent a full year in Florence! Students didn’t stay that long anymore, didn’t have the same kinds of experiences. She reached back, took hold of that spirit and wrote the damn letter to the Conte. Her daughter would correct it when she came home from school, and she’d deliver it by hand. If he really were a nobleman, he’d reply. And if he didn’t, at least she would have made her request, at least she would have reached out, gone beyond the drafting phase, and asked for what she wanted, and maybe obtain it, which was all she ever wanted to learn how to do anyway.