- Exhibition display creates comparison

- Spotlights on the works

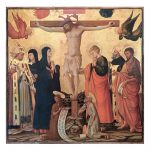

- Comparisons between paintings and painted sculptures

- Neri di Bicci, Crucifixion, Rignano sull’Arno (Firenze), chiesa di San Lorenzo a Miransù

- Don Romualdo da Candeli and Neri di Bicci, Crucifix, Firenze, palazzo Medici Riccardi

- Workshop of Desiderio da Settignano, Santa Costanza, detta La Belle Florentine, Paris, Louvre

- La Belle Florentine compared to a portrait of the same period

- Madonna del Presepe (La natività), painted terracotta, Bologna, chiesa di Santa Maria dei Servi

- Donatello, Crucifix, Florence, Santa Croce

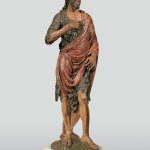

- Francesco da Sangallo, San Giovanni battista, Bivigliano (Firenze), pieve di San Romolo

- Desiderio da Settignano and Giovanni d’Andrea, Maddalena penitente, Firenze, basilica di Santa Trinita

- Andrea Cavalcanti detto il Buggiano, Maddalena orante, Pescia (Pistoia), oratorio della chiesa di Santa Maria Maddalena

- Michelangelo, Doni Tondo

- Francesco del Tasso, Detail of the frame of the Doni Tondo

It’s fascinating how museum display and art history textbooks seal the fortune of certain artists, artworks, and even entire media. If I ask you to name a famous Renaissance sculpture made in wood, you might be hard pressed to remember one from your art history classes. Perhaps you’d come up with Donatello’s Mary Magdalen in the Opera del Duomo Museum – if so, give yourself 10 points. Maybe you fuzzily recall something about a painted and sculpted crucifix by Brunelleschi at Santa Maria Novella, which study abroad students in Florence usually look at in relation to Masaccio’s Trinity in the same church. Give yourself 15 points. Those may be two of the best known painted wooden sculptures in Florence, two that, thanks to their locations and famous makers, have had a greater critical fortune than the many works in the same medium that have remained unknown to the general public. An exhibition at the Uffizi Gallery seeks to change that.

The show is called “Fece di scoltura di legname e colorì“, La Scultura del Quattrocento in legno dipinto a Firenze (He made coloured sculpture in wood, Quattrocento painted wooden sculptures in Florence) and it runs from March 22 to August 28, 2016 in the temporary exhibition area of the Uffizi Gallery. Gathered for the first time are some 50 works, mostly by Florentine artists, tracing the medium through the entire 15th century. The exhibition display, designed by Antonio Godoli, takes the viewer through a maze of small rooms, where single spot lighting creates a dramatic focus on works organized to create comparison and contrast either by subject matter or medium.

But why haven’t we considered painted wooden sculpture much in the past? In part, it’s a historic bias: Vasari didn’t think much of it (though he does cite some works made by masters like Donatello in wood). Michelangelo privileged marble, and most of the Renaissance did so too. Wood is a cheaper material, one that was used primarily for devotional objects, and these objects were destined for churches, where they continue to function to this day. As such, even if sometimes they were sculpted by the “big names” of the day, the coloured part was considered of secondary importance, and when it wore down – due to use in processions, accumulation of soot, or whatever reason – the object would be repainted, sometimes 5, 6, 8 times over. In some cases, especially in the 19th century, wooden sculptures would be overpainted to look like bronze or marble. Their value as an object of art in its own right has been undermined throughout the centuries.

The exhibition at the Uffizi has been an opportunity to census the works in churches, to bring them in for restoration, and finally to show them to the public. It’s also been the occasion for academic study, producing a catalogue that brings together writings by both top and emerging scholars, often with intentionally divergent ideas. Finally, one of the most interesting things that this show does is that it is generating attention to a type of work that will soon move back out of Florence’s largest museum and into their homes in the city’s churches. This is it’s biggest gift to the city.

The catalogue already includes a section of six works that were unable to be moved for the show, including important crucifixes in Santa Maria Novella, San Lorenzo and the Duomo, suggesting that we visit them in situ. There is also an essay “mapping” painted wooden sculptures around Italy, outside of Florence. The one contribution the catalogue lacks, and that we could create based on it, is an actual map of works to be seen in Florence starting next Fall. That map would list the big basilicas (Santa Croce, Santa Maria Novella); it would remind us to look at the high altar of the Duomo (where the crucifix by Benedetto da Maiano has recently come out from under a 4-year-long restoration); and it would bring us into lesser-visited churches like Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi or Sant’Ambrogio, both of which house impressive works sculpted by Domenico del Tasso and his workshop, combined with paintings by the likes of Filippino Lippi and Raffaellino del Garbo.

Seeing the works reunited and getting the recognition they deserve is the first step; making sure we don’t forget, but continue to observe and study them is the hoped-for future.