“No meaning, no symbols, no sense” was one pre-war American verdict on mining magnate Solomon Guggenheim’s collection of abstract art. Echoes of that public resistance to painting and sculpture with no recognisable subject matter are still heard today. Why does abstraction leave many people scratching their heads? As the astonishing selection from the collections of Solomon and Peggy Guggenheim at Palazzo Strozzi demonstrates, art that depends on form, colour and gesture empowers the viewer’s personal perceptions.

Abstraction was the dominant creative force in the visual arts of the last century. As one of its pioneers, Wassily Kandinsky began to strip away descriptive detail from his landscapes of folk imagery around 1910. Strong colour and dynamic line became his route to expressing spiritual reality in painting.

Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944),

April 1936. Oil on canvas, 129.2 x 194.3 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection 45.989.

Photo by Kristopher McKay

Kandinsky’s Dominant Curve welcomes visitors to Palazzo Strozzi’s highlights from the Guggenheim collections. When made in April 1936, late in his career, Kandinsky was fascinated by embryology and botany; numerous light-coloured organic shapes appear to circulate within the perimeter of the painting like basic life forms seen through a microscope.

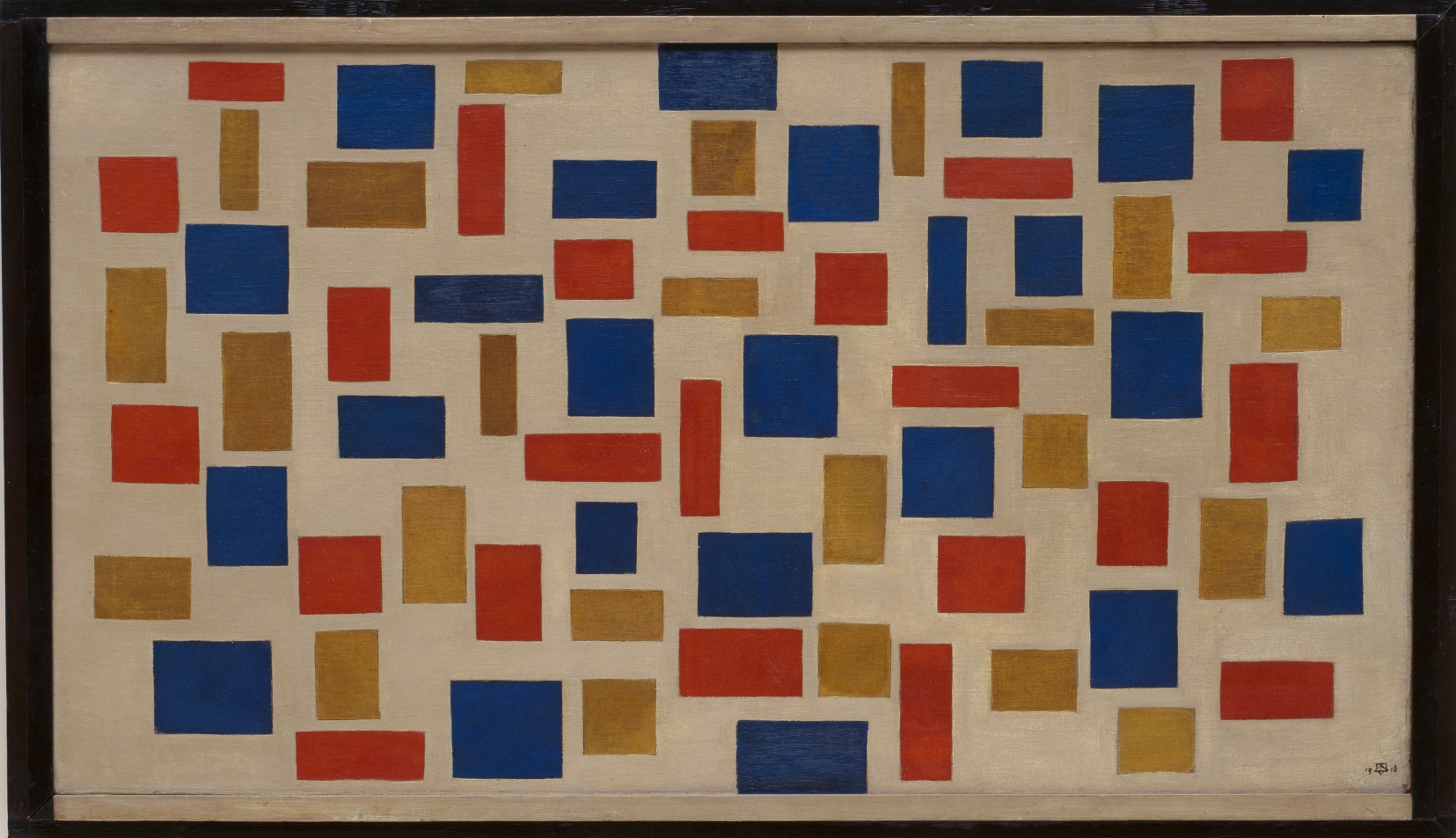

Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931),

1918. Oil on canvas in artist’s frame 64.6 x 109 cm (73.2 x 117.8 cm), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 54.1360

Photo Ellen Labenski

Nearby is Dutchman Theo van Doesburg’s Composition XI from 1918. Here, too, buoyant shapes float on the white surface of the canvas. But these forms are roughly rectangular and colour is limited to subdued red, yellow and blue. In radical contrast with Kandinsky’s image of teeming energy, this composition is in search of its own quiet balance, a sensation it conveys to the viewer.

Indeed, this range from rigorous geometry to restless biomorphic shapes represents the span of abstraction in this show. Between Kandinsky and Jackson Pollock its development unfolds across 50 years and nine rooms, taking the story to the 1960s, when Cy Twombly’s mute but urgent script of circles and rings dances off the tense curved edges between solid areas of black and white in Ellsworth Kelly’s boldly structured canvas.

Along the way the visitor’s senses are buffeted and elated by form, tone and gesture as if walking through frequent changes in the weather. The expressive impact of paintings by Hans Hofmann, Willem de Kooning, Sam Francis and Joan Mitchell animates space itself. Their room is churned and pummelled by colour that appears to move forward and back as it drips and swirls. Paint is at one moment thin and vibrant and then dense and muscular.

Two artists are accorded their own galleries. In one, 18 works trace the decade-long evolution of Jackson Pollock’s painterly language from turbulent, ritualistic symbolism to completely abstract, his “all-over” style exemplified by Watery Paths from 1947, for which Pollock trailed paint from a brush or stick as he circled in rhythmic movements round the canvas laid flat on the studio floor. The result is dizzying: an intoxicated surface of crisscrossing tendrils of colour and matter. The imagined space they enfold is simultaneously physical and mental.

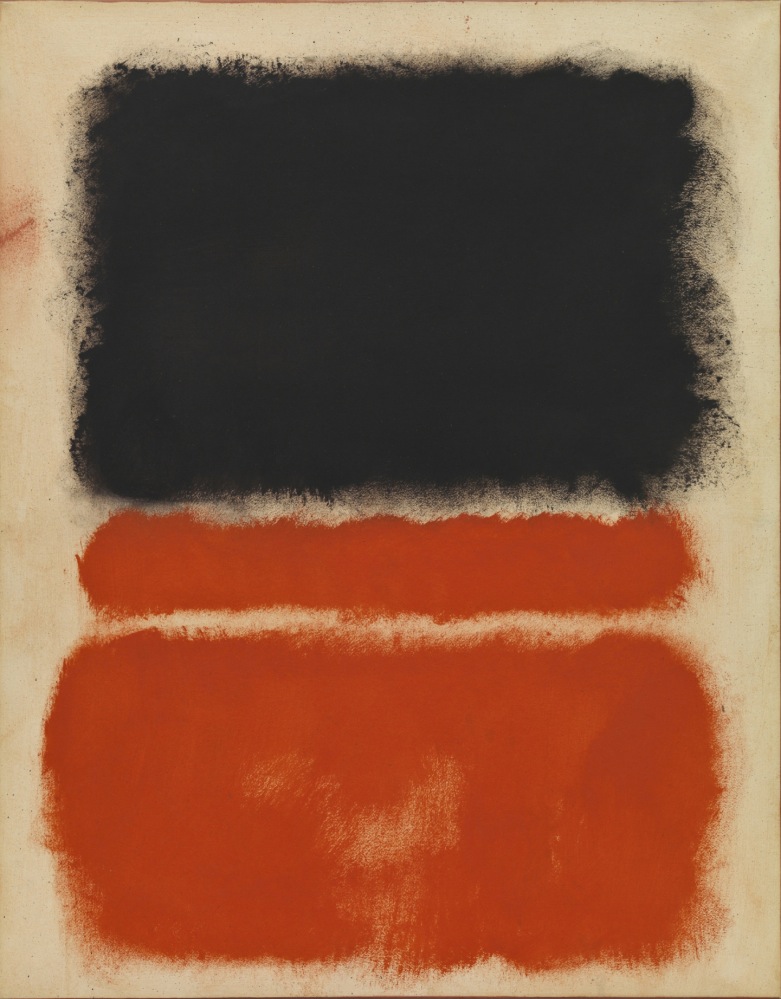

Mark Rothko (1903–70), 1968. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 83.8 x 65.4 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012, 2012.92 Photo by David Heald © Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ARS, New York, by SIAE 2016

In another, a mini-survey of Mark Rothko’s work, five spotlit paintings hang on black walls. Their surfaces of orange, burgundy, red, brown and black in soft-edged rectangles infiltrate the room and hover like vapour clouds modelled by atmosphere. Rothko’s work echoes Kandinsky’s search for spiritual reality, culminating in Untitled (black on grey) from 1969 to 1970, made just before he died. A still horizon separates flat, cold colours; light has gone, and with it hope.

This exhibition tells three stories. Abstraction occupies the first while the second starts when Solomon R. Guggenheim retires from business after the Great War to devote his wealth to collecting art. The new non-objective styles were suitably progressive for the new world and free from Europe’s tainted traditions. Guggenheim’s museum first opened in New York in 1939, transferring 20 years later to a startling building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright—a setting every bit as advanced in taste as its contents.

The third story belongs to his independent niece, Peggy Guggenheim. A freethinker who broke rules, this remarkable woman brought artists together who eventually transformed the post-war art scene. Mixing young Americans with Europeans like Max Ernst, Fernand Léger, Piet Mondrian and Marcel Duchamp—artists who came to New York to escape the Second World War—fresh ideas flew like pollen. Pollock and Rothko were among the beneficiaries.

Having lived in Paris and London, Peggy Guggenheim’s interests went beyond abstract art. She liked Surrealism and acquired the prime pieces by Picasso, Brancusi, Jean Arp, Paul Delvaux and Max Ernst (whom she married), shown here in the first two rooms. In wartime New York she opened her own gallery, aided by Marcel Duchamp and the architect Frederick Kiesler, who devised an extraordinary interior. Curved walls were hung with paintings on wires that could be moved and rotated, like books in a library. Lights flashed in dreamlike settings designed to stimulate the imagination. Back in Europe, Peggy Guggenheim quickly decided to settle in Venice. She supported Europe’s avant-garde artists, hanging Francis Bacon’s painting of a chimpanzee by her bed. Her palazzo on the Grand Canal housed her personal museum, which, always concerned to widen access to new art, she opened to the public.

There is, finally, a fourth story in this exhibition, related to Palazzo Strozzi itself. After the authorities in Turin rejected the work as too modern, in February 1949, Peggy Guggenheim’s collection opened the new cellar galleries of the Strozzina. Although no stranger to theatrical presentation, the palazzo’s galleries have not revived Kiesler’s innovative display techniques for this return visit. Instead, the lucid and restrained installation is exemplary. The work is placed centre stage to transform our individual experiences.

From Kandinsky to Pollock. The Art of the Guggenheim Collections

Until July 24, 2016

Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

www.palazzostrozzi.org