The Vasari Corridor was commissioned by Cosimo I de’ Medici from Giorgio Vasari in 1564, on the eve of the marriage of his son to Johanna of Austria; the kilometer-long “monumental urban footpath” connects the south side of the Palazzo Vecchio to the Medici family’s then-residence at the Pitti Palace. It goes through the Uffizi Gallery and leaves on its south side, passing over lungarno degli Archibusieri and following the north bank of the Arno until it crosses over the Ponte Vecchio.

From the Vasari Corridor ph. Rebecca Edwards

At the time of construction, builders were forced to build around the Torre dei Mannelli using brackets, because the owners of the tower refused to alter it. The corridor covers part of the façade of the magnificent Mannerist church of Santa Felicita, where the Medici families celebrated Mass unseen and away from the public. The corridor then snakes its way over rooftops of homes in the Oltrarno district. Becoming narrower, it finally joins the Palazzo Pitti next to the Grotto of Buontalenti, inside the Boboli Gardens.

The collection of self-portraits housed in the corridor was started by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici in the seventeenth century and was once exhibited in the Uffizi in “The Hall of Painters” (now dedicated to Michelangelo). It was taken down in the nineteenth century and relegated to the museum storehouses until 1973—when nearly 600 paintings out of the 1,800-piece collection were exhibited in the Vasari Corridor. Though widely celebrated, this prestigious series of self-portraits has a little-known claim to fame: it boasts the highest concentration of works by women artists available for public viewing in the world.

Self-portraits by pioneering women artists from the 1500s include those of Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, Arcangela Paladini and Tintoretto’s daughter, Marietta Robusti. During the 1700s and 1800s, Florence became a hub for female creativity and the collection was enhanced with works by Rosalba Carriera, Angelica Kauffman, Mary Benwell and Rosa Bonheur. A work by Bolognese artist Lucia Casalini Torelli accompanies paintings by noblewomen of her time, including Maria Antonia Walpurgis and Dona Mariana Waldstein, as does a work by Violante Siries Cerroti, who portrays herself as an artist. Cerroti’s students Anna Bacherini Piattoli and Maria Hadfield Cosway are also part of the collection.

The twentieth century saw the arrival of interesting self-portraits by Cecilia Beaux and Nabis painter Elisabeth Chaplin, while, in 2010, more works by women artists were added to the collection, such as portraits by Carla Accardi, Vanessa Beecroft, Mirella Bentivoglio, Giosetta Fioroni, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jenny Holzer, Yayoi Kusama, Ketty La Rocca, Patty Smith, Alison Watt and Francesca Woodman, to name a few.

To make the corridor accessible via a moderately priced ticket and to safeguard these paintings from exposure to extreme temperatures in summer and winter, the Uffizi’s director Dr. Eike Schmidt plans to replace current artworks with detached frescoes or Roman sculptures. The goal is to transfer at least 50 of the Corridor’s most famous self-portraits into several rooms of the Uffizi’s piano nobile—their original location—by the end of 2017. Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun’s portrait, recently the star of Met’s monographic exhibition, is sure to be among them (though, in her own era, the artist caused a scandal for having painted herself with an open mouth and visible teeth).

My question is, will other self-portraits by women artists, currently in the Vasari Corridor, continue to have visibility in the Uffizi’s hallowed halls? Will visitors still have the chance to meditate on the collective power of art history’s greatest women protagonists?

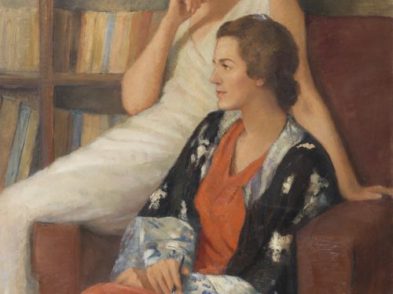

Rotation is one possible solution for the 600-plus pieces that will be transferred. Temporary shows are another. The Uffizi’s gesture of loaning Adriana Pincherle’s Self-portrait to the exhibition on the artist hosted at Palazzo Panciatichi-Covoni this spring was an interesting overture of what the future may bring. Thus, this full-length painting reminiscent of Modigliani and the French avant-garde became ‘godmother’ to the 2016 edition of ‘Women Artists of the 1900s’, spearheaded by the Advancing Women Artists Foundation and Associazione Culturale il Palmerino.

A master of color, Pincherle depicted herself holding an easel, after having wiped her paint-filled hands on her otherwise white skirt. Normally in storage, her painting is a reminder of the unseen treasures by women artists that await rediscovery. Her self-portrait, as well as the dozens of others on display or in storage in the city’s museums, represents the vital need to safeguard Florence’s forgotten cultural wealth so that these artists’ past and future may be fully reclaimed.