The search for history’s hidden stories has always been one of my personal passions. It was this passion that brought me to piazza Santissima Annunziata one autumn morning in 2012 to explore the Innocenti Museum, in the company of its head curator Eleonora Mazzocchi and Florence-based restorer Elizabeth Wicks. The museum was closed to the public that day and a deserted museum always inspires an air of mystery.

But the real excitement began in the ground-floor storeroom of this enormous venue, where they had recently discovered nine unpublished sketchbooks belonging to Czech painter Antonietta Brandeis (1848–1926), which provide incredible insight into the artist’s creative process. With wonder, we leafed through a dozen of her exquisite watercolors on paper and pressboard, as well as through personal photographs that she had squared off while searching for details to use in her works. This treasure trove of works needs restoration and includes scenes from Florence, Venice and Rome—the cities where the artist most often travelled and exhibited.

Brandeis was born in 1848, in the Czech village of Miskowitz, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In Prague, in her early teens, she learned the basics of painting landscapes, portraiture and religious subjects as a pupil of Karel Javůrek (1815–1909), considered one of the founders of Czech historical painting. After her father’s death, Brandeis’s mother remarried a Venetian and the family moved to Venice in the late 1860s. She enrolled at the Venetian Academy of Fine Arts as one of their first women students and would complete her studies there in 1872, three years before the Ministry granted women the legal right to instruction in the fine arts. (Brandeis and her English classmate Caroline Higgins were the only two women in that graduation class.)

Temple of Antonino and Fausta

During Brandeis’s time at the Academy, she was awarded countless prizes and honors for her artistic skills in several fields, including life, landscape and sculptural drawing. Brandeis showed her first works in Florence and Budapest, under the male pseudonym ‘Antonio Brandeis’, because she became annoyed whenever critics praised her as a ‘woman artist’.

She later became a favorite of Grand Tour travellers in Venice, imbuing her works with intricate details, after the tradition of eighteenth-century vedutisti (from the Italian word ‘veduta’ or ‘view’).

Italian vedutisti, following in the footsteps of Canaletto, usually created large-scale painting or prints, which focused on landscapes and seascapes in rural and urban areas.

When her Venetian husband died in 1909, Brandeis took up residence in Florence on via Mannelli, where she continued to paint in her studio until her death on March 20, 1926. Several interesting paintings bear witness to her time in Florence. She donated four works to the Pitti’s Gallery of Modern Art, all of which are currently in storage. Her best-known painting, The Niobe Room at the Uffizi, features a woman artist painting there. It faithfully depicts the room’s arrangement at that time (as per photographs from the City’s archives). From this work, it would seem that Brandeis spent time copying the Old Masters at the Uffizi.

Though the artist revered the city’s more famous museums, her heart would forever belong to the Innocenti Institute, to which she bequeathed the majority of her art and worldly possessions—including her home. Preserved in the Innocenti’s archives, Brandeis’s will dated January 1, 1922 provides an interesting window onto her unique character: ‘I do not wish my corpse to be defiled by the usual toilette. Whatever state I am in, I wish to be wrapped up in a shroud which also covers my face. I do not wish to give rise to those curious to see how ugly or how beautiful death is. I want my funeral to be very simple and without any flowers, but a Christian one, which I am with my entire soul. I don’t want my friends to have to accompany me in procession… I would like the Ospedalino degli Innocenti, my universal heir, to say a mass for my soul on each anniversary of my death.’

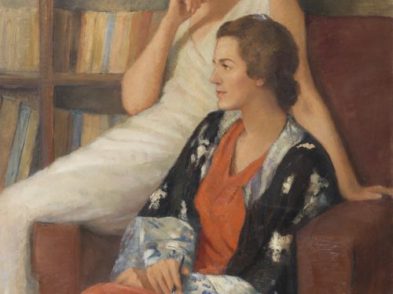

Brandeis’s portrait, painted in 1924, by Laura Capella, hangs in the Institute’s benefactors’ room. There are many missing pieces in her life history, but in her day, as a woman, we know she confronted and even challenged several social conventions. In today’s terms, she was a trailblazer for future artists!

The impressive expansion of Florence’s Innocenti Museum, with its 1,500 square meters of exhibition space, is reason for celebration. Its renovation brings renewed attention to the stories of the countless children raised in what art historian Alexandra Korey credits as ‘the first lay institution for childhood and infancy in the world’. It is my hope that Brandeis’s art may one day be restored and exhibited for all of Florence to appreciate. Her philanthropic and creative ties to one of the city’s foremost charitable institutions deserve rediscovery.