As soon as the 1966 flood is mentioned, most Florentines recall the mud-covered streets, the tired smiles of the young Mud Angels and the wounded works of art carried away from the churches and museums. Then there is Cimabue’s Crucifix.

Two days after the flood (by then it was November 6) the volunteers finally gained access to the Museum of Opera di Santa Croce, only to find the Vasari face down in the Arno waters, which by that point had filled the Cenacolo by about 11 feet. Umberto Baldini, the director of Istituto del Restauro, described that firsthand encounter: “Cimabue was dying. And he was taking with him, by ransacking the museums and churches, entire centuries of works of art, damaged, split, unrecognizable, on which the mud, water and oil had inflicted damage at random, in death’s cruel embrace.”

The Crucifix, which due to its exceptional character had survived intact and in perfect condition for almost 700 years, in the days of the flood became “a last manifestation of the Apocalypse,” according to Giuseppe De Micheli, director of Opera di Santa Croce. That single image quickly became the universal symbol of the Florentine flood.

Yet, with the crucifixion, also comes a story of resurrection. After a painstaking restoration by Opificio delle Pietre Dure lasting 11 years, the Crucifix, with a staggering loss of 55 per cent of its painted surface, was returned to Santa Croce in a civic celebration in 1976. Shortly afterwards, for the first and probably last time, Cimabue embarked on a world tour, organized by Italian IT company Olivetti, with scheduled stops in New York, Paris, London, Madrid and ending in Munich in the fall of 1983.

Ph. courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art for use in The Florentine

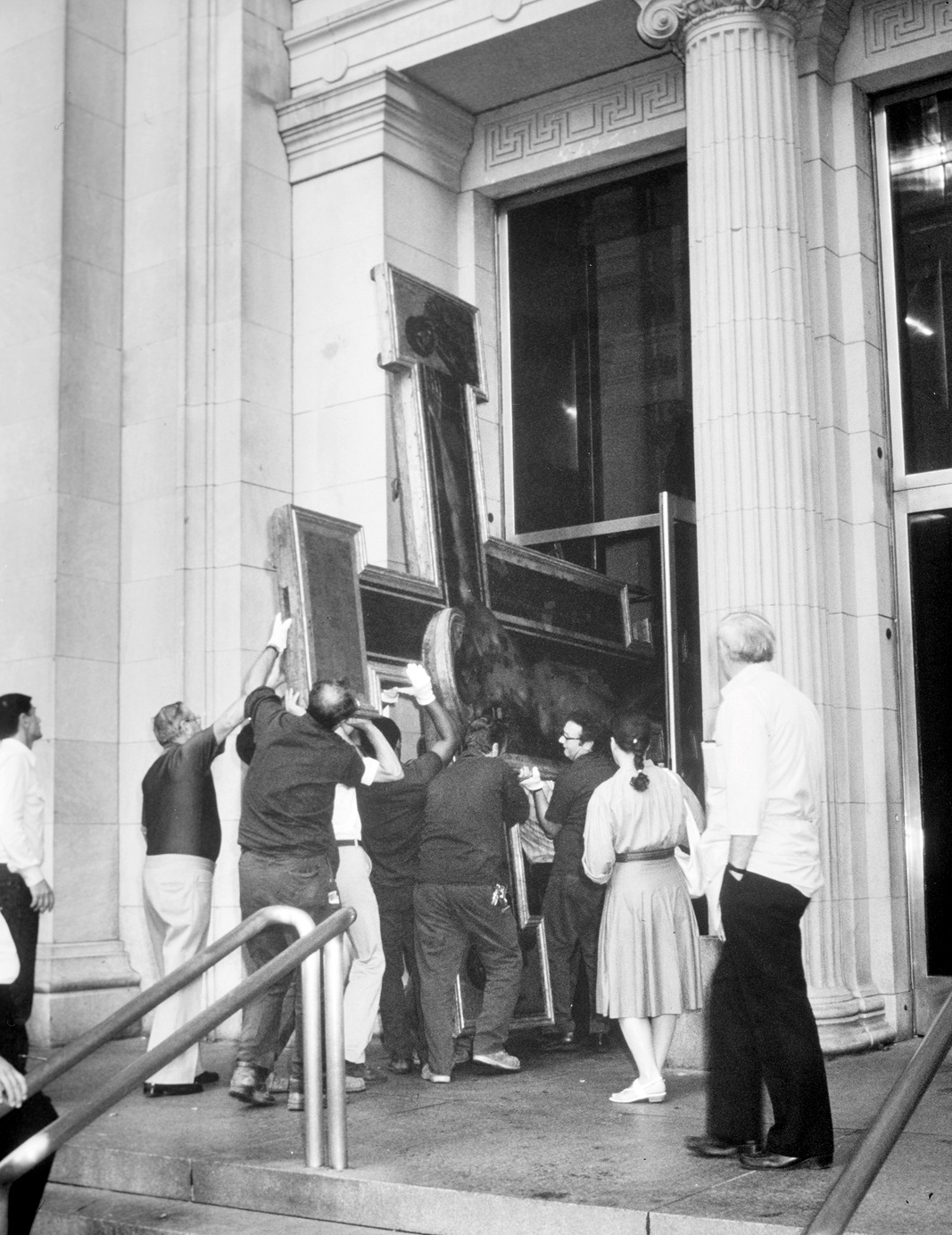

The 1982 photographs from the exhibit at The Metropolitan Museum, taken as the Crucifix was hand-carried through the main door of the museum (measuring 14.5 x 13.5 feet, it was too large to enter through the side entrance), disconcertingly resemble the photos of Italian soldiers who had carried the masterpiece to salvation in 1966, out of the gates of Santa Croce and far from the Arno to the higher grounds of the Boboli Gardens.

Ph. courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art for use in The Florentine

The exhibition, which opened in New York on September 6 and ran until November 11, 1982, proved a great success. According to a letter scribed by the Met’s president Philippe de Montebello, dated September 23, 1982, the exhibit had already been seen by almost 15,000 visitors.

The catalog of The Metropolitan Museum exhibit poignantly sums up the flood: “Death came to men and to animals. Houses, shops and workshop were polluted and their contents ruined, but what chiefly seized the imagination of the world was the destruction and damage to works of art in a city universally regarded as the source and repository of much that is most valued in the culture of the Western world… This affront to the human spirit is even now still being made good.”

Referring to the star of show, the catalog reads: “The damage to the great Cimabue Crucifix was the most serious artistic loss in the Flood; its infinitely painstaking restoration must be regarded as a defence of spiritual as well as artistic values… It is a testament to Cimabue’s genius as well as to the patient care of the restorers in Florence that even in its present condition the Crucifix retains the power of a great work of art.”

I remember years ago, I asked one of the old Franciscan friars in Santa Croce if he ever visited the United States, the answer was “No, never. But Cimabue did.”