- Doryphoros

- Doryphoros

- Donatello’s David

- Michelangelo’s David

- Battle of the Horsemen, Bertoldo di Giovanni

- Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker

- Michelangelo’s Lorenzo de’ Medici

- Young Hercules, Peter Paul Rubens

- The Digital Michelangelo Project

Little can be said on the subject of Michelangelo Buonarroti that has not already spawned centuries-long discussions and analyses.

Michelangelo’s career inaugurated “the cult of personality” that elevated the role of artists to unprecedented grandeur, transcending age-old principles that previously veiled painters and sculptors in anonymity. This accomplishment was aided by the effusions of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, wherein Michelangelo is chronicled as “an artist who would be skilled in each and every craft … (and) acclaimed as divine”. Yet for all his trailblazing talents, seen most passionately in the medium of sculpture, Michelangelo derived equal inspiration from both the Ancient and Early Renaissance makers that preceded him. Loosely influenced by the innovative postings of justsixdegrees.com, whose project based on “six degrees of separation” theory links creative pioneers across the globe, here lies a visual chronology of the works which came to inspire (or be inspired by) Michelangelo’s masterful sculptures.

Doryphoros / Polykleitos

With Michelangelo’s sculptural approach firmly rooted in classical ideals, it is no surprise that the initial point of inspiration for his famous David—from resting stance to body shape—can be traced back to the Ancient Greek statue of Doryphoros. Brought to life by Polykleitos circa 440 BCE, his may have not been the first to use contrapposto, but the sculpture’s well-muscled proportions and classical realism proved impactful on Roman art movements and, by extension, Michelangelo’s formative years, sketching and studying amongst the ancient sculpture replicas in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s garden of San Marco. While essentially all Roman copies of Greek statues were crafted in marble, original sculptures were fashioned out of bronze, the same material used by Donatello to produce the first male nude sculpture since antiquity.

David / Donatello

The links that tie Donatello and Michelangelo are fundamental. Though their paths never physically crossed, the two figures are seamlessly connected. For example, Early Renaissance sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, who instructed Michelangelo in the Medici garden, studied at Donatello’s workshop and ultimately became his head assistant. Moreover, Michelangelo openly regaled Donatello’s classical sculptures, deemed the greatest of the 15th century. Though Michelangelo’s David later surpassed that of Donatello’s in the eyes of critics, the latter played a crucial role in re-introducing nude male sculptures to artistic production after a dry spell of over 1,000 years.

Battle of the Horsemen / Bertoldo di Giovanni

As mentioned, Bertoldo di Giovanni played a pivotal role in Michelangelo’s artistic evolution. Whilst nurtured under di Giovanni’s classically-centred tutelage, and still enjoying Lorenzo de’ Medici’s patronage, the burgeoning sculptor crafted his Battle of the Centaurs at just 17 years of age. The tangible depth and three-dimensionality of this marble carving set the tone for Michelangelo’s defining approach, alongside an unfinished roughness that set the course for his non finito sculptures (a concept first conceived by Donatello). The direct influence for Battle of the Centaurs was di Giovanni’s Battle of the Horsemen, a visually arresting bronze relief based on the adornments of ancient Roman sarcophagi.

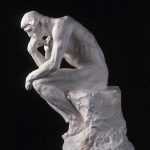

The Thinker / Auguste Rodin

An instrumental innovator in 19th-century art scenes, Rodin’s sculptures drew bountiful influence from the non finito works permeating Michelangelo’s back catalogue. Defying the pristine, perfectly smooth techniques of French academia, his rough-textured works were conceived after careful analysis of Michelangelo’s Young Slave and Awakening Slave sculptures. Rodin’s closest mirroring of the High Renaissance master is evidenced in The Thinker, with a heroic nude male figure emulating Michelangelo’s sculpture of the same name.

Young Hercules / Peter Paul Rubens

In a similar sequence to that of Michelangelo and Donatello, Rubens became enthralled by the former’s creative output during an eye-opening trip to Italy in 1600. He poured over the composition of Michelangelo’s figures and was compelled to sketch reproductions of these muscular sculptures as well as works from other artists of note. Rubens could not know the future significance of these detailed sketches, particularly when considering his illustrated model of Michelangelo’s Hercules. A significant statue likely commissioned in memoriam for Lorenzo de’ Medici, it shifted from Medici to Strozzi possession before leaving Florence for France, where it sadly vanished from written history. Its visual memory nonetheless lives on, thanks to Rubens’ über-muscular sketching (this Hercules illustration currently resides in the Louvre, Paris).

The Digital Michelangelo Project

The concluding notes of this six-part thread could reference the contemporary reworkings of classical sculptures, from Fabio Viale’s tattooed figures to the tongue-in-cheek, marble-made hipsters of Léo Caillard and Alexis Persani. But given Michelangelo’s spearheading of three-dimensional techniques, it couldn’t be more fitting that the latest paean to his mastery utilises the ever-evolving medium of 3D printing. A collective of computer scientists from Stanford University kick started the Digital Michelangelo Project, 3D scanning the artist’s prized sculptures using laser technology and then 3D printing identical physical replicas. Process-wise, it’s a far cry from the years Michelangelo spent carving his David out of an enormous marble block, but the initiative ensures that Michelangelo’s legacy continues along its immortal path.