After months of bated breath, the most recent conjuring of New York’s Met Gala, an impossibly lavish annual gathering woven together by fashion’s master-puppeteer Anna Wintour, made for a truly eye-popping soirée, the ensembles of its star-studded attendees quickly devoured by public onlookers.

As is now standard practice in this age of digital immediacy, a sea of online spectators descended upon the garments of honoured guests before they had even finished their walk (or saunter, as this portion of the night is known for being remarkably drawn out) up the red carpet. With each year’s dress code themed around the latest Met exhibition to be unveiled—the Gala thus acting as its official inauguration—2018’s one sartorial rule for the night was “Sunday Best”, a nod to the museum’s newest and most ambitious showcase yet: Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. Displayed across a staggering 60,000 square feet, encompassing 25 galleries in the process, the exhibition melds an impressive array of couture ensembles (just over 150, to be precise) with approximately 50 pieces from the Sistine Chapel Sacristy, many of which having never ventured beyond private quarters previously.

There’s little doubt that, for guests who followed Wintour’s dress code, a thoroughly more-is-more style ethos dominated attire. Merciless fashion commentators @diet_prada, a witty duo of Instagram darlings recently unmasked as Tony Liu and Lindsey Schuyler, treated their nearly 470k followers to a barrage of satirical shaming and praising of Met Gala attendees. Kate Bosworth’s channeling of “a breathtaking, holy apparition of The Madonna” in her Oscar de la Renta look was regaled, while Amanda Seyfried golden-yellow Prada number was transformed into an uncooked-spaghetti meme. The vast majority of theme-followers were found to have hit the mark: Naomi Watts embodied a modern reimagining of embroidered Vatican capes in her Michael Kors dress; Gigi Hadid’s Versace gown, with its resplendent ode to stained glass, was one of few frocks to reference church architecture; and last, but certainly not least, Rihanna made a striking play for the leader of a new religion with her papal-esque Maison Margiela outfit, every conceivable inch of fabric covered with gems and jewels.

The Vatican may have officially given their seal of approval to “Heavenly Bodies”—another chapter in Pope Francis’ long list of reformative innovations—but the Met Gala’s immediate aftermath was met with a torrent of criticism from dyed-in-the-wool Catholics. Wintour’s role in cultivating the most expensive night of the fashion calendar was slandered. With a table ticket coming in at $275,000, designer gowns a median $35,000 and over 550 people primed to attend, no expense was left uncriticised. Twitter warriors couldn’t imagine why the Church whose values are so enriched in modesty, aiding poverty and inclusivity, would join forces with such an extortionate event. Yet such backbiters have overlooked the sumptuous expenditure long enjoyed by Catholic rulers: as much (if not more) entwined in the religion’s fabric than its fight against impoverishment.

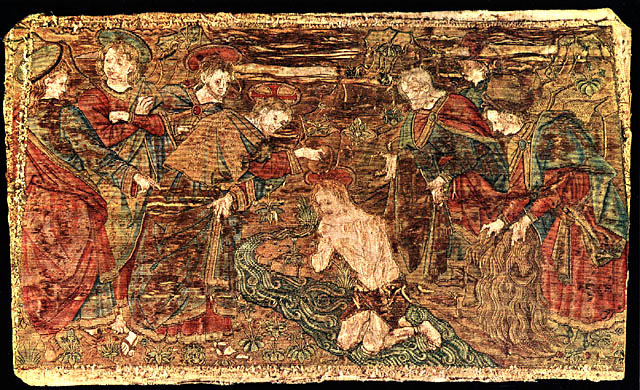

Antonio del Pollaiolo’s Embroidered Vestment, Jesus Baptising John the Baptist, Opera del Duomo, Florence, Italy

A key part of Heavenly Bodies explores the influence of Catholicism on fashion over the years, and while this may, partly, manifest in the Met through jewel-encrusted crosses adorning racy dresses, the Church played a crucial role in the flourishing textile trade of Renaissance Florence. While acting as generous patrons across all spectrums of the arts, the expensive gold-work embroideries (known as or nué or oro sfumato) that thrived in the Tuscan capital from the 1300s to the 1600s were commissioned, in an overwhelming majority, by the Church itself, often to embellish liturgical vestments. Incredible three-dimensional scenes were depicted through the dexterous use of silk threads, split stitches and satin stitches in a kaleidoscope of colour. The background material was usually linen or heavy cotton, harnessing the city’s equally thriving cotton trade, and emulated the detail of paintings to the highest degree. The value that Florence’s Catholic leaders placed on embroideries can be measured, as one example, by 15th-century record books. One 14-year-long commission embroidered scenes from the life of S. Giovanni, designed by Andrea del Pollaiolo and achieved, according to Giorgio Vasari, “with the most delicate mastery and art”, saw eleven master craftsmen from a variety of countries engaged in this work, bringing its total cost to “3179 florins, 7646 lire, 10 soldi, 8 denari”. The Church’s investment in the most luxurious of sartorial offerings was cemented, and given this era’s tendency to merge religion with politics, it is little wonder that four members of the Medici family ended up claiming the throne of the Papal States, where their penchant for ornate furnishings and fabrics was more indulged than ever. Thankfully, some fruits of the embroiders’ labours (including those S. Giovanni embroideries) can be marvelled at in Florence’s Opera del Duomo Museum, where the abundance of brightly coloured silks and golden threads (thought by one Pollaiolo specialist to “gleam like plates of pure gold”) can be judged with one’s own eyes.

Before building any pre-conceived notions that Heavenly Bodies is the fashion world’s subjective seal of approval towards the Catholic Church, it is worth considering some of the powerful statements made on the Met Gala red carpet. Trailblazing actor and producer Lena Waithe, having already made history as the first black woman to win an Emmy for comedy writing, traversed uncharted territory once more in donning a silk rainbow cape at the Gala, honouring LGBTQ communities whilst provoking thought for its tumultuous history with the Catholic Church (and religion as a whole). Moreover, Rihanna’s aforementioned “papal power” look was applauded by multiple observers as denouncing the fact that women are barred from serving as Catholic priests and, by extension, ever becoming Pope. The Church may still be grappling with archaic principles whilst attempting to integrate into modernism, but with Anna Wintour leading her industry into an equality-embracing age, her long-existent (if unofficial) onus as “the Vatican of the Fashion World” couldn’t be in more capable hands.