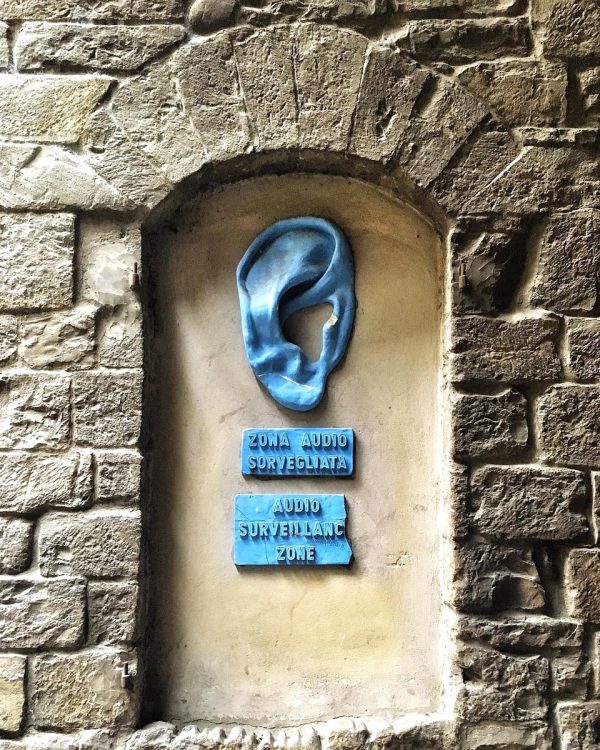

At this time of year more than any other, Florence invites us to be cognizant of the complexities lurking in the liminal, transitional spaces that illuminate the city’s countless historical thresholds. Before we find ourselves like Dante, halfway through our lives, frightened and feeling like we are lost in a dark wood, we should remember that traversing these spaces can be disorienting in our own modernity. One such space that seems indifferent to the passage of time sits quietly on vicolo della Seta: Palagio di Parte Guelfa

Neither imposing nor inviting, the palace of the captain of the Guelf party stands as a testament to the impulses of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but it is often overlooked by both Florentines and rushing monument seekers. Construction started in the 14th century, but during the Renaissance it was profoundly influenced by the talent of Filippo Brunelleschi, Francesco Della Luna, Giambologna, Luca della Robbia and Donatello.

Brunelleschi left the deepest imprint. His legacy rests on striking design in sacred architecture like the perfectly proportioned Pazzi Chapel at Santa Croce and the soaring dome gracing the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, but this is only the tip of the iceberg. The founding father of the Renaissance consulted on the design of bridges, fortifications, hydraulics and public works. Regardless of the project, he was a risk taker—his model for a Medici palace was rejected by Cosimo il Vecchio for being dangerously ostentatious. With the same impetus to push boundaries, he designed a grand space for the Palagio. The Sala Brunelleschi bears witness to his commitment to the harmony found in classicism. Significant portions of the medieval palace were destroyed in the 1430s to make room for these renovations. Brunelleschi’s design found itself encased in a medieval skeleton. If you attend one of the many talks held in this recently restored soaring space, it is easy to forget that by the 1440s the Guelf party was constrained by Medici power and that their money was being directed elsewhere. Knowing this, the calm harmony of this space as we see it stands as a ruse.

There is considerable irony to be found in a keenly harmonious space in a palace that evokes the memory of a civil war, which was made vicious by the constricted setting in rapidly growing medieval Florence. The conflict between the pro-papal Guelfs and the Ghibellines, who advocated for feudalism and the authority of the German emperors that racked Italy in the 12th and 13th centuries, was explosive in Florence. So much so that when one party stood triumphant they made a show out of confiscating or destroying enemy property.

Hundreds of structures in Florence belonging to the Guelfs were razed during a rare period of Ghibelline control between 1260 and 1267. A definitive show of power, destruction of memory and clear illustration that returning from exile would be no easy task.

The Palagio reminds us that it was the Guelfs who held power most often in Florence. Systematic exile forced their perceived enemies over a threshold into the unknown. Dante, the most infamous victim, was not allowed to return to the city for not being pro-papal enough in the eyes of the Black faction of the Guelf party. He grappled with a future that was unfamiliar and, at times, unimaginable. It was precisely this liminality, the dissolving of tradition and the loss of identity that made the “Supreme Poet” a swansong of the Middle Ages. Cruelty, it seems, can create space for epic creativity. Dante enters the journey of The Divine Comedy by stepping into that aforementioned forest in 1300, at the height of the Guelf and Ghibelline struggle. The city was traced by a physical footprint defined by the fortifications that defended it. Beyond that threshold was threatening, alien territory, and that is where Dante found himself.

In the name of progress, much of that footprint has been destroyed.

Florence’s walls were torn down, the medieval artery of the city was cleared for a proper modern piazza to acknowledge a unified Italy, and attention has turned away from the Palagio in favor of the busy streets offering shopping between the Duomo and piazza della Signoria. Despite the lack of contemporary fanfare, the Palagio served as the headquarters of a republic inside of a republic in the late Middle Ages. Its 70-member council dominated Florentine affairs, a dominance that Machiavelli later lamented as abuse of power.

Under Medici pressure, the Guelf party dissolved. Its headquarters became a space that stands as a husk from a distant past. When places lose the function that they once had, they become liminal spaces. The Parte Guelfa was revived in 2015 as an archconfraternity of the Catholic Church in Florence, but the space is dominated by the offices of Calcio Storico Fiorentino and Corteo Storico della Repubblica Fiorentina. In liminal spaces, reenacting the past can seem to amplify its distance. Even for a historian, standing in the sweeping Sala Brunelleschi can be unsettling because it can no longer serve its intended function. It is a reminder that liminality at its core comes from our own minds, from our own unsettled reality.

In Florence, we struggle in the present with the push and the pull between the past and future.

The Roman God Janus, January’s namesake, was depicted with two faces, one facing forward and the other looking back. He served as a gatekeeper evoked by those on a journey, just as the Palagio di Parte Guelfa reminds us of the potential found in transitional spaces as we journey into the coming year. Dante didn’t stand paralyzed when facing the unknown; neither should we.

Join Christine Contrada for a free academic lecture (January 11, 10.30am, Palagio di Parte Guelfa, piazza della Parte Guelfa 1) titled “Over the threshold in Dante’s Florence: Reimagining liminal spaces created by the strife between the Guelfs and the Ghibellines”.