There was a time in my life when food and my body became the enemy, when every meal was an accounting—I would break up my day’s rations into a mental list, stacking items one on top of the other. If the tower grew too high, I panicked. When writing my novel, Florence in Ecstasy, I gave this affliction to my protagonist, Hannah, who is in Florence in the aftermath of an eating disorder. On a horrific, multi-course dinner date at a Tuscan restaurant, Hannah strips down naked in the bathroom to try to see herself in the fogged mirror. She inventories what she’s eaten, then inventories her body. I never ended up stripped down in a restaurant bathroom, but the scene came from an impulse that was genuine. Like much of fiction, it wasn’t me but it could have been.

And, like Hannah, for my 22-year-old starved self, Florence was a place where I learned to love food again. I had always had a relatively healthy relationship with eating and my body, but my first year out of college was rocky. It was 2001 and at the same time as I was discovering my vocation in teaching and finding a home in the classroom, I watched the Twin Towers crumble, and the city that had always been my home became a stranger. After the smoke cleared, I found safety in not eating. By the time I arrived in Florence the following summer, I’d spent many months at war with my body.

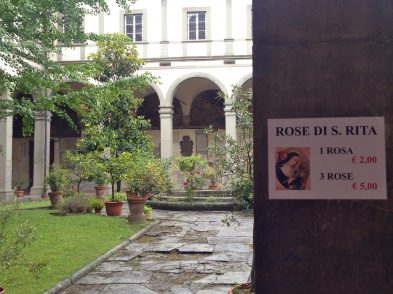

Ph. Marco Badiani

My counting and categorizing of food was ritualistic. Stubborn and spiritual, it was rooted in the deepest part of me, and to loose myself of it required new rituals. In many places, but certainly in Italy, food is ritual—both its preparation and meals themselves. While studying abroad in Florence years earlier, I’d taken classes at Apicius Cooking School, and now I returned for a course in Tuscan cuisine. Back in the kitchen of the small apartment I’d rented, I tried to perfect the recipes. It was one of those very hot summers, thick with humidity, thick with mosquitoes, the city near-empty of Italians by August, and still I spent hours in that kitchen cooking fried zucchini blossoms, pappa al pomodoro, rice-stuffed tomatoes, fresh pasta with pesto, tagliata with rosemary, tiramisu.

I got lost in the process—learning to request in Italian the correct cut of meat at the market; weighing out vegetables on the small scales; measuring out cups and spoons of oil, garlic, cheese; feeling for the pull and elasticity of pasta dough; smelling for the smooth acidity of a balsamic sauce before it turned too crisp and charred; beating and beating eggs and mascarpone so that the tiramisu would hold its form. These new rituals became a part of me, and as I prepared meals, I found myself forgetting to count.

And, importantly, I didn’t just cook—I ate. I ate things I wouldn’t normally eat because by the time a dish was ready, I was connected to it. I knew it with my body. And this was more than exceptional food—it was food with context, food with history, and it became a part of my history. The class’s textbook, Gabriella Ganugi’s The Four Seasons of the Tuscan Table, is still on my shelf. Stained and torn, the slim volume is a reminder of the recipes embedded in me that summer.

There is a learned feel to every dish and also a learned science—so that your pasta isn’t overcooked and your tiramisu doesn’t end up a plate of watery cheese. The science of healing is less direct. There were days when I denied myself or tried to compensate, biking for hours or walking too long in the hot sun to negate calories. There were moments when the only reason I didn’t remove all my clothing and inventory my body was because there wasn’t a private bathroom or a mirror. But slowly my relationship with food changed and I came back to my body—I sometimes still hated it, but I came back.

Learning about food, working with food, finding pleasure in food didn’t only return me to my body—it also upended the isolation that comes with an eating disorder. It enabled me to connect with other people again. I returned to Florence numerous times, with family and friends and then with my husband for a year while I was finishing Florence in Ecstasy. Every trip, I developed deeper friendships, many of them formed over meals that were themselves elaborate rituals, multiple courses stretching late into the night, the extra glass of wine or amaro creating just a little more space for conversation, a little more time to be together.

Whenever I’m in Florence now, food is front and center, as both a delicious epicurean experience and a ritual that binds me to a place that I love, to the memories that a particular dish holds, to the history of evenings spent around tables with friends, to a self that learned to enjoy, and continues to enjoy, eating. Also with me in those moments is the ghost of my eating disorder because, like any addiction, it didn’t simply vanish. I don’t believe we’re miraculously cured of our vulnerabilities. Continuing to survive them requires vigilance so that when we’re most at risk, we don’t lean back into them. But what requires equal, and perhaps greater, vigilance is holding onto their opposite—pleasure, joy, and connection. Because, as Hannah observes in the novel, These things, too, add up. These things, too, count. They stack to form a complete whole.

The novel

Hannah, a young American, arrives in Florence from Boston, knowing no one and speaking little Italian. But she is isolated in a more profound way after a bout with starvation that has left her life and body in ruins. She is determined to recover in Florence. Get your copy in English or Italian