My brother learned to swim when he was fourteen, by jumping off a promontory. Our father usually took us on vacation to the coast, but not the kind of beach with umbrellas and lifeguards.

He would make us wash our canvas shoes before they started to stink; by the end of the season they’d be yellowish from bleach. While he plunked out a few songs on the restaurant piano, my brother and I would play cards on the benches in the laundry room hypnotized by the metallic thudding of shoes in the spin cycle.

The day he dove off, I leaned over the edge of the promontory. I didn’t know how to swim either; I’d only learn years later, with the help of a patient young man I thought I was in love with and that my brother made fun of for not drinking and having narrow hips. When he re-emerged from the Spanish broom with dirt all over his feet, his chest was covered in streaks, like he’d been slapped.

That evening, since I hated sleeping on the cot, I slipped into bed with them as they watched a movie where girls were taken hostage at a bank and then escaped with the robbers, or where dobermans tore their owners to shreds. During the night I slumped over onto my brother’s chest; my dad got angry when he found me sleeping that way. At breakfast he made us drink milkshakes with raw eggs in them, and mocked my brother for not putting on any weight.

One day he’d sat down on the ground in front of me with his mouth open; he wanted me to pull out his tapeworm. I put a popsicle stick on his tongue, waiting for the larva to come out and wrap itself around the wood. We sat there for fifteen minutes, but nothing happened.

My brother kept getting skinnier, but he had clean teeth, the color of pale ivory, and hair down over his ears that smelled like baby shampoo.

He was the handsomest boy I’d ever seen. When he started going out with girls from his class, I’d hide under his bed waiting for him to get back and tell me what happened, and as soon as he said he’d kissed them, I’d stick my head under the pillow in feigned embarrassment.

Once I took malaria pills to make it through a summer in the city.

I couldn’t afford to go on vacation, I was living on my own and was just out of college. I went to a clinic specialized in tropical diseases and lied to the doctor, describing a trip to Ghana as an aid worker. I’d purchased sunscreen with the highest SPF they had at the drugstore and even cut my hair in the interest of practicality; the hairdresser said to make sure I moisturized to keep it from getting scorched by the African sun.

I sat in the doctor’s office for over an hour, as he talked to me about specialization courses abroad that he’d had to pass up for the sake of his family. I smiled sympathetically, looking at the photos on the wall: those daughters of professionals that always have braces or the sensual androgyny of swimmers.

Antimalarials could cause rarefied trance states, lucid dreaming, muscle weakness, dizzy spells, and buzzing in the ears; even auditory hallucinations.

The first dose did almost nothing. The second time I went out for a walk through my deserted neighborhood; I smiled in a daze at people who bumped into me and leaned my head against shop windows to recover from the heat. I felt much thinner, faster, like I could walk all the way to the sea; I took my shoes off to feel the warm, soft asphalt, but then a cramp in my stomach made me lie down on the ground as a garbage truck picked up its load of trash, buried there among foil trays and sleeping dogs.

It was a summer of long thunderstorms, with white phosphorus skies in between.

During my weeks of malaria treatment, I took walks along the river, left a bar without paying the tab, and fought with my best friend.

I ate out on the balcony, attracting the neighbors’ cats. My body was full of mefloquine but had no illness to fight off; my boyfriend had dumped me, but kept calling with reminders to water the plants he’d given me. Their leaves were covered in red bugs, and sometimes one would crawl over my legs, its fuzz visible under the streetlight. I’d promised the doctor I’d send him a postcard.

A few years later I started traveling for real; I’d been hired by a bimonthly science and technology magazine. It had glossy, fluorescent covers that stood out on waiting room tables.

My sister-in-law had passed my name on to the editors and my brother had called to say “You’re smart, you’re healthy. You need a job,” as I scratched off the layer of wax that covered my kitchen table, the flakes digging deep under my nails. I spent my days varnishing shelves and dying fabric with Japanese techniques illustrated on the web.

I didn’t know how to dress for formal meetings. That time I showed up to the interview in my Superga shoes, jeans, and a black blazer, because that’s how important women dressed, the kind that raced in regattas or did live feeds from Fallujah.

I called my brother to tell him I’d gotten the job, he seemed pleased.

He took me out for pizza and we talked about horror movies, he said I looked good with short hair. I hadn’t grown it out since that summer I never went to Ghana.

The magazine had a ’90s budget; it was on the brink of collapse but the editors didn’t want to adapt to the changing market, and I was one of the last reporters to take advantage of the situation. I was sent to do a story about people living in bizarre dwellings around the world.

I went to the Canary Islands, where I slept at a Holiday Inn and the staff would invite me out to dances. I was supposed to interview a Welsh guy who had moved to a floating house that stood on a platform of garbage; he’d built this little island by tying together bottles and empty OJ cartons, wrapping wooden crates in big black plastic bags. It was a ramshackle design. On board I found a hammock, a generator, and a strange bathroom made of rope. The owner had fixed me breakfast with oatmeal and coffee, he never used lighters. The windows were covered in newspaper clippings and articles about the royal family.

Then there was the former TWA pilot. With his pension money he’d bought an old airliner and a piece of land big enough to park it on, a field in Virginia. His grandfather had patented a special kind of adhesive tape, leaving him a sizeable inheritance. Inside the remodeled plane, we talked long-distance: he handed me a pilot’s headset and we sat there joking with each other from opposite ends of that aircraft buried in the woods. At night he slept in the cockpit, which was luxuriously furnished. Cherry furniture and brass ashtrays, a solitary life. Before leaving I looked out a window and breathed in the smell of pines that wafted through cracks in the sheet metal.

I met up with a couple from Sussex who had moved to the country after buying a modular house from the ’70s designed like a spaceship; only a few still existed around the world. Her husband had built the furniture to fit its spherical shape. They grew herbs for medicinal use, but weren’t hippies; they looked more like rich art dealers.

I wrote a sentimental piece that went on about wildlife, solitude, and moon landings. My editor said it was great, but not right for the magazine. It was never published, even though between travel and expenses it cost over ten thousand euros.

“I think I’m addicted to people. I’ve never drunk or smoked, never shot up. But people. It’s like I wanted to snort them whole, get inside their stomach, and it’s never enough,” the TWA pilot told me as we sat in front of the dead control panel aimed toward the woods with no way to take off, and the crickets made an ear-splitting din.

On one of those trips I met a man. We were staying at the same crowded hotel and sat by each other one morning at breakfast; I noticed two of his fingers were banged up, with the keratin of the nails all purplish and milky, and asked what had happened. “When I’m stressed I do carpentry projects,” he said, showing me photos of the treehouses he built for his friends’ children.

The conference we were in town for had ended ahead of schedule because a speaker dropped out, so we went to a museum together, wandering among the paintings.

I’d left my gloves at home, and when we came back down the street of slate buildings crusted over with verdigris, he slipped my hand into his pocket to warm it up, as we bounced from cafe to cafe looking for something to eat.

On the way back, I leaned my head against the bus window and he stroked my neck, sliding one finger under the edge of my sweater. He was wearing an aggressive cologne and too much of it; at the museum it made me woozy when he got close.

That evening I showed up at his door wearing the robe from the bathroom. I came in without looking at him and sat down on the bed, pulling my hair over one shoulder, head bent to see whether my toenail polish was chipped. He leaned against the damask wallpaper in front of me, crossing his arms, and at that point I got up to open my robe, but didn’t let it fall to the ground.

From then on I started calling him before I went to sleep, whenever I was traveling alone. My phone calls were brief, syncopated, sad.

He never asked me anything personal. How I was, whether I was feeding myself properly, what color the sheets were in my hotel rooms, if I’d picked up any parasites on some unusual trip; instead he talked to me about the properties of crystals, the resistance of certain bodies to water. His voice was low and light, he’d laugh for a long time, and listening to him talk was soothing.

After a year of phone calls I started wearing an engagement ring with an amethyst set in a silver band, and later began telling taxi drivers I was married.

In the pauses of those conversations I could hear the echo of his kids, doors banging, dogs, crinkling bags, sounds that reverberated in my head even though they didn’t exist, even though I was the one making them, as he told me it was impossible to fall in love that way.

At around forty I married a diplomat and started working with foreign think tanks, sometimes as an interpreter, more often as a wife. For our first anniversary he gave me a collie that barked all the time and despised strangers; I’d never had a pet before.

At official dinners I always lied about my life. The only true thing I said was that I could barely swim, which inspired immediate affection and incredulity in the rich men who invited us out on their boats.

My husband used to surf and had to get a bolt put in his knee as a kid because he’d wrecked his legs doing a trick on his skateboard; every time he came back to where I was sitting cross-legged on the beach, smiling as I recognized his approaching form, he’d break into a sprint and fling himself headlong to crush me under his damp, heavy, wetsuited body.

“You’re hopeless, but I love you just the same,” he’d say, and I’d soak up all his energy, like a machine designed to refract his happiness and warmth millennia away. I liked watching him engrossed in activities aimed only at pleasure; sex with him was amusing, exhausting, free of danger.

He made me think of something the man I always phoned at night had said, that last evening we spent together before going our separate ways.

“What happens to memory when they put us through an X-ray machine?” I asked as he was taking off my clothes.

“I don’t know, but with X-rays your cells can undergo slight mutations. Maybe the ones holding a memory split in half, and the memory gets distorted.” That was a trifling answer, the radiation is so weak it doesn’t even affect the growth of your fingernails, but I believed him.

Over the years of our long-distance relationship we sent each other photos to see what we’d become; he didn’t like his own looks and would send ones that were sort of blurry, with him wrinkling his forehead or wearing a sweater in my favorite color.

I tended to take slightly greater pains, I didn’t put on makeup but posed with my lips a bit parted.

My last assignment for the science magazine before I moved abroad and got married involved taking part in the simulation of an interstellar voyage funded by a videogame company.

The safety personnel had me put on a suit and harness, swapping jokes about my weak pulse.

I was a little dazed by the promoters with their questionnaires, the mega screens showing virtual data on the hostile environment where we’d be landing, the domesticated strangeness of that launch.

That’s how I discovered that the heart becomes something cumbersome and real, when there’s no gravity: all at once all you are is pulsing blood and lead, the heaviest thing no longer on Earth.

Translated by Johanna Bishop

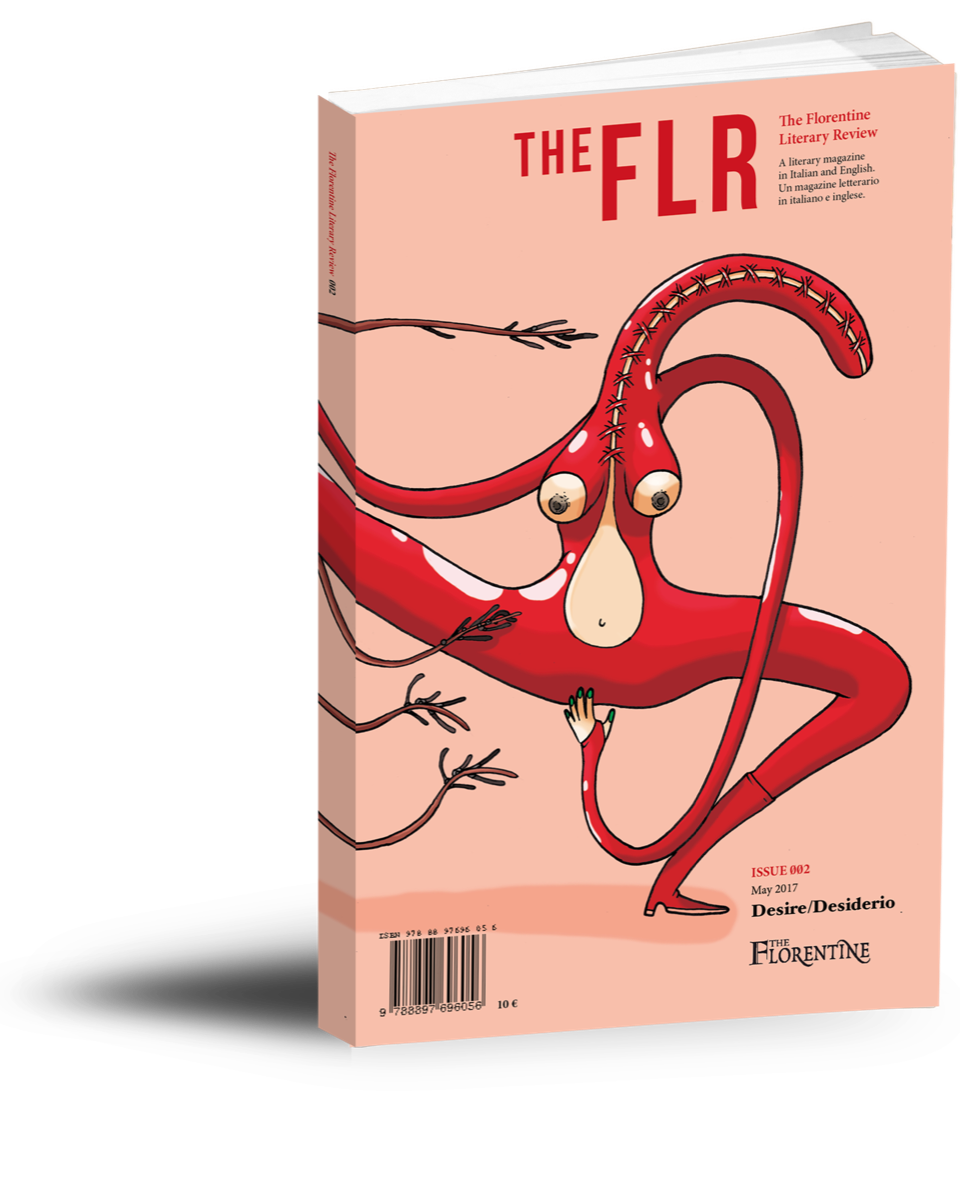

Illustration by Adam Tempesta

The Florentine Literary Review – issue #2 DESIRE

Read contemporary Italian authors in English with TheFLR. Buy it direct and make a saving.

Available in Florence at Todo Modo and Paperback Exchange bookstores