The event planner of the 15th century has to be Giovanni Rucellai, who, having successfully arranged the marriage of his youngest son to the granddaughter of Cosimo de’ Medici, bankrolled a feast for the senses.

Bernardo and Nannina’s wedding, spread over three days in June 1466, took place in the piazza in front of the newly completed Palazzo Rucellai. To accommodate the more than 500 guests in attendance—and to pander to what was no doubt an even larger crowd of gawkers—an enormous triangular stage was constructed in front of the house. Stretching approximately 3,000 square feet from the palace façade across via della Vigna Nuova to the far edge of the Rucellai loggia, the platform was raised some three feet off the ground and crowned with an awning of bright blue cloth. Decorated with rose garlands, tapestries and the entwined Rucellai and Medici coats of arms, the pavilion, “the most beautiful and finest ever made for a wedding banquet,” was filled with “very beautiful furnishings,” the host tells us, “very rich.”

Sandro Botticelli, The Wedding Feast, 1483. Credit: Private Collection/Bridgeman Images.

Rich, indeed. By Rucellai’s own calculations, he spent 6,638 florins on the whole affair (the median cost of a palace in the mid-15th century was between 5,000 and 10,000 florins). From Sunday morning until Tuesday evening, 50 cooks prepared lunch and dinner in a makeshift kitchen set up behind the palace, in the piazza of the church of San Pancrazio, and in the connecting side street, via dei Palchetti. No expense was spared on provisions, which included 2,800 loaves of bread and 4,000 wafers; 1,500 eggs; 2,496 chickens and small birds, and about 700 ducks; saltwater seafood and silver-scaled fish from the Arno; lard, sausage and tongue; mozzarella di bufala; baskets full of sweetmeats, tarts and pomegranates; and 120 barrels of wine, local and Greek. Piled high on gold and silver platters, meals were marched out by servants dressed in matching livery; for tights in the family colors, Rucellai allocated 290 florins, serving up gastronomical and sartorial excess in healthy portions.

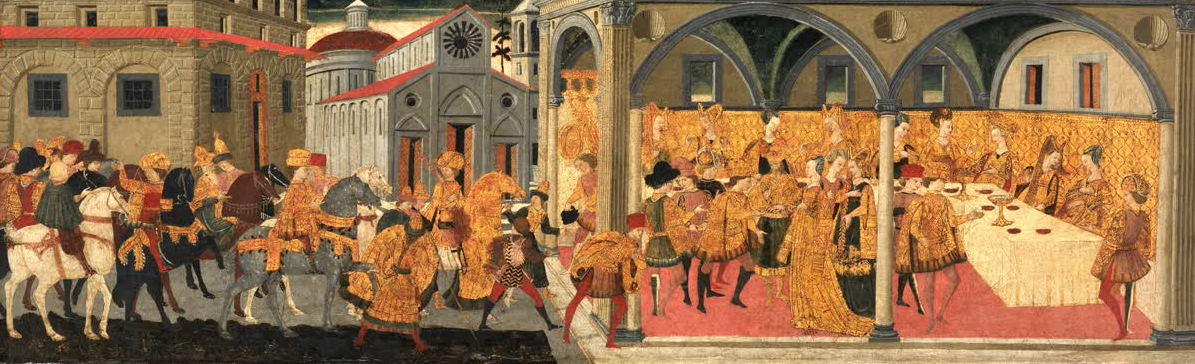

The dramatic setting and sheer extravagance of the Rucellai–Medici wedding are suggested by a 15th-century cassonepanel depicting the marriage of Esther, a biblical story transposed to contemporary Florence. Against a monumental backdrop of family palace and parish church, the king and his retinue process across the piazza toward an Albertian loggia, lushly outfitted for a wedding banquet. Guests draped in gold brocade blend seamlessly into the gilded tapestry hanging at their backs, while bride and groom, equally encrusted, are wed in the foreground.

If the Rucellai–Medici wedding party oozed such opulence, consider the gushing bride. Nannina’s top-drawer dowry included satin gowns of every color embroidered with gold thread, nightcaps embellished with diamonds, velvet slippers and pearl-laced stockings, silk gloves and ivory combs, plus three small knives, a spike and a fork. Silverware—a whole new way to accessorize! Not to be outdone by the Medici, Giovanni welcomed Nannina into Palazzo Rucellai with a substantial counter-dowry: velvet gowns with fur-lined sleeves, hair ornaments, shoulder brooches and necklaces dripping in diamonds, rubies and pearls.

The marriage market in 15th-century Florence was obviously big business. It was also well seasoned with a rhetoric of consumption, not to mention gluttony. A letter of 1465 between Alessandra Macinghi Strozzi and her son Filippo, for example, describes the numerous girls she has considered for him, “because if you want a gourmet meal, you need to order it in advance.” (For all her heady matchmaking, when it came down to choosing a daughter-in-law, Alessandra went with her gut, crudely boasting of the successful candidate, “she’s good meat, with lots of flavor.”) A good marriage, as Giovanni’s bookkeeping indicates, wasn’t cheap; nor was it inconspicuous. “It is unbelievable how much is spent on these new weddings,” complained the Florentine chancellor Leonardo Bruni. “Habits have become so disgusting.”

Marco del Buono Giamberti and Apollonio di Giovanni di Tomaso, The Story of Esther, c. 1460–70. Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1918.

Some may have recoiled at the prospect of a big wedding, but Giovanni relished the opportunity to flaunt his new wealth, surely justifying the inordinate cost of the wedding as a shrewd investment in his and his son’s future.

In fact, long before Bernardo and Nannina ever exchanged vows, Giovanni had begun to capitalize on their prospective nuptials, boldly incorporating into the design of his palace façade Medici family emblems: interlocking diamond rings in the spandrels and double-feathered diamond rings in the lower frieze—rocks set in stone.

But this was a love story tarnished from the start. Her father-in-law may have been filled with joy, boasting as the man who had himself wed a Strozzi only to win a Medici for his son, “Our house has been able to make the principal marriage alliances of this city,” but the young Nannina had a different view of things: “O do not be born a woman if you want your own way.” Clearly, the nozze had left a bad taste in her mouth.