Bestselling author Sarah Dunant has written 12 novels and worked for the BBC, presenting The Late Show as well as the historical podcast When Greeks Flew Kites. Set in the Italian Renaissance and combining cutting-edge historical academia with fast-paced fiction, Dunant’s most recent novels have been translated into 30 different languages.

Sarah Dunant

Paola Vojnovic: What brought you to Florence and interested you about the Renaissance?

Sarah Dunant: I’m one of those people who have history in their blood. I’ve always been passionate about it and I grew up loving historical fiction; I read hundreds of books. I studied history very seriously at a very good English university and basically had all the romance beaten out of me by an academic education, but I never lost that sense of an umbilical cord, and in all my work as a journalist I was always looking for the context, the history, the roots where we grew from. Then about 20 years ago, having started to write crime fiction, I found myself in Florence for a period of time on my own. Anybody who’s ever been to Florence will have exactly the same reaction, I’m sure, as I did; it’s not a period I had studied historically so I was quite new to it. The question that comes to you as you walk those streets is: What the hell happened here 550 years ago to make this small, parochial city the cauldron for one of the greatest cultural revolutions that Europe has ever seen?

PV: How did the history open up to you in Florence and how did you find a female character?

SD: When I was at Cambridge University, I don’t think I wrote a single female name in any essay; that was how we looked at the past. Needless to say, in the last 30 or 40 years feminism has had the most extraordinary impact on history, and so the question that I asked myself—did women have a Renaissance?—had indeed been asked by a scholar called Joan Kelly.

When I went back in order to do my research, what I discovered is that there was a vast underground lake of history that scholars were trying to penetrate about women. For instance, we now know that there was one extraordinary female painter in early 16th-century Florence: Plautilla Nelli. She wasn’t even known about; she was the abbess of a convent. It was stuff like this that was coming to the fore. I had all of this going on: the academic work that you do when you’re trying to write about history. Then you’ve got to bring it alive and to bring it alive you have to find characters, so I started to revisit all the places I’d been to in Florence with another question in my mind: I’m looking on the walls for women and I’m looking for real women, I don’t want Mary Magdalene, I don’t even want Botticelli’s Venus. I want to know what real women I’ll find.

PV: You know, Sarah, they say that people in the world are divided into two groups: those that love Florence, and those that love Venice. So which group are you in?

SD: Well, I lived on and off in Florence for 20 years, so of course I would have to argue that my heart would always be in Florence. And there’s a very good reason for that over Venice, as we know, because Florence still has some sense of being a contemporary, alive city that is part of a modern sensibility and culture. Venice has suffered from becoming hollowed out by tourism, and that has done us no favours when it comes to imaginatively attempting to reconstruct what Venice would have been like in the 15th and 16th centuries, when nobody felt sorry for her because she’s not a city sinking; she’s a city wooing. She is one of the wealthiest, most powerful cities in the whole of Europe, and she has a stability and a pride and a sense of self-esteem that barely any other city has.

It was in that moment, in the Accademia, that the character of Bucino, my dwarf who is the first person narrator of In the Company of the Courtesan, was born. So I think you see the way in which I’m always driven to the art. The art brings it alive, gives me the people, but in the background I’ve always got the academic and historical study to know what they’re doing there, to give them graft, so that the characters grow out of the historical reality. For me, that’s enormously important in historical fiction. It’s very easy for historical fiction just to be the likes of you and I in pretty bodices and dresses, for us to always think they’re exactly the same as us. In some ways, they were the same as us, but they grew from a very different culture, a very different sense of sensibilities, very different political and religious circumstances, and to understand that you have to grow them out of their own soil. For that you need a mixture of the British Library and every art gallery and show that you can visit.

PV: In terms of your book Blood & Beauty, how hard – or indeed easy – was it to research the Borgia family and to write about them?

SD: This is really interesting because another question, which you sent to me earlier, was about the role of historical writers setting the history straight. Somebody mentioned that they’d been reading Hilary Mantel and the work she’d done on Thomas Cromwell. For me, there’s too much Tudor history in the world. Everybody knows the Tudors, but there’s a whole rich panoply out there, and when I was looking for women to continue to study in the Renaissance, there is one woman in history who has been given the worst time by historians that is possible to imagine: her surname is Borgia, and her Christian name is Lucrezia. Poison, incest, voluptuousness, sexuality, murder, you name it, Lucrezia’s meant to have done it. My job was to tell the story about how this 13-year-old girl, who will have three husbands by the time she’s 21 (because she is a pawn in a dynastic game), has come to be seen by history as evil incarnate, and what her true story was.

PV: And this is where your magic comes in, you’re able to do this for all of us, which is an extraordinary gift.

SD: Well, it was my first love. I was pulled into history by story, and therefore I think it’s vitally important that if you tell it, firstly you make it a damn good story and secondly you get your facts right. The facts are there to be known. And if you get your facts right, the psychological portrait of the people that you are trying to create will be true to their roots in all of their complexities, which probably means I can introduce you to the very last person I’m working on.

PV: I love that you’re going to tell us about your new research and what you’re doing now, which is so extraordinary and very exciting.

SD: I am 80,000 words into a novel about this woman, Isabella d’Este, who was born into the small city state of Ferrara in the late 15th century and she marries into another powerful small city state in Mantua, both of which are little Renaissance jewels. The reason Italy is the cauldron of [the Renaissance] is because there are many little city states with rulers who have the money and education to want to be players in this cultural revolution. Isabella d’Este is the first serious woman patron that we have in the history of art. She’s born into beauty, she has a natural affinity for it and she will go on to create a collection of Renaissance art, which is unparalleled by a woman at any point. It doesn’t exist any more because, along with the rest of Mantuan art, when Mantua goes bust in the mid-17th century it’s bought by Charles I before he has his head chopped off, and then that whole collection goes on sales scattered throughout Europe.

She’s the original photoshopper. She is not a good-looking woman. She very early on has an extremely sweet tooth, and starts to “spread”. And when she gets herself painted, if she doesn’t like the result she ditches the painting. So Mantegna, another fabulous figure, does a painting of her and she just destroys it because she says it doesn’t look like her, which probably means it looks exactly like her! She commissions Titian to paint a painting, and the age she is when he delivers it is 63. The story is that Titian did a painting to her and sent it, but it obviously didn’t look like this. So she sent him another painting that she’d had commissioned 30 or 40 years earlier, which had also made her more beautiful, and said “copy this, but put these clothes on it” (because the other thing she is, is a fashion icon). So what we have here is a woman who controls in a way that hardly any woman in her period does, right down to the images that she gives us of herself through history. My task, if you like, is to make her, warts and all, really likeable. I should say that sometimes there are odd moments, working on Isabella d’Este, when I will find myself being very bossy. I said to my husband ,”I think I might be channeling Isabella” and his priceless remark was “it’s better than being three years in the company of Cesare Borgia”.

PV: I’m sure it’s not easy to sit with you as you are so immersed in your research. I had the pleasure of having dinner with you one night and you were just finishing Blood & Beauty, and I remember just how much you lose track of time, you know, the day and night doesn’t fully matter and I think that’s absolutely incredible. I wanted to ask you one thing; I think it’s really wonderful to talk about what we can learn from history, so what would be the one thing that you could connect to our really difficult times of the pandemic – what rings a bell?

SD: Okay, two things. The first is pandemic. Plague. We have been hit by a disease that we have never come across before, that is highly contagious, that will kill us, that we have no cure from, and we’re panicking because it’s moving really fast. History is full of these moments. I’ve been researching how Isabella d’Este runs the city of Mantua while her husband is away and one of the jobs she has is controlling what happens when the bubonic plague breaks out again. The Black Death was two centuries ago, but we never found a cure for that, so what happens is it keeps coming back. As I was researching this, this is what happens in 1506 when the plague gets close: first of all, Mantua closes the city gates against all visitors coming from a place where they might have connected with the plague: the airports and train stations of today. Secondly, you set up a quarantine hospital, usually just outside the city gates, and people who show symptoms are taken into the quarantine hospital where they will have to stay. Quarantine originally comes from quaranta – 40 days – and they have to stay there for that length of time until they either contract it and possibly die, or they’re allowed to go free. And then if there are areas of the city where it’s just getting out of hand, they corner off the whole area of the city and it goes into lockdown, and they police the lockdown. The only thing that’s allowed in is food and doctors. The final element is – and tell me if this isn’t a description of now – that a good government understands that there will be a terrible economic toll as a result of this. And so they’ll check what the price of corn or wheat is for bread and they will release more supplies to make sure that the poor aren’t suffering too much. And when the plague finally passes, they will bring people out of those quarantine hospitals and there will be processions to thank God and will give them arms to start a new life. So I think that what we have to learn from the past is that you have to be humble when stuff hits you that you don’t know, and with any luck history will give you some advice as to how to handle it.

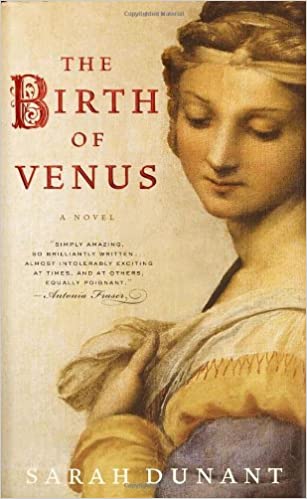

‘The Birth of Venus’ by Sarah Dunant

PV: Which one of your books would you suggest reading first?

SD: Oh, I’d start with The Birth of Venus. I think, to quote a horrible cliché, you can feel the love. The book grew out of love. I was in love with the Italian Renaissance, I was in love with the idea of what it would have been like to be a young woman educated in humanism – and I didn’t yet know what I was doing. It was beginner’s luck. That book was extremely successful. Now I read it and see only what’s wrong with it, but what I do know is it has a kind of passion about it. I’m a better writer now, my historical knowledge is infinitely greater – Isabella d’Este, I hope, will be a very complex character – but you can just feel it.

PV: How many hours a day do you write and are you structured about it or does it come in a freestyle way?

SD: When I was writing the first five of these books, I would write at least four, five, six or seven hours a day; I would find it very hard to stop. I promised myself and my partner with this Isabella d’Este book that I would not become as consumed. Of course, that’s proved more difficult than I expected, but the genuine answer to that is when I’m not writing, I’m still writing. When I’m cooking, when I’m walking, when I’m cleaning, when I’m gardening, when I’m trying to fall asleep, I’m still absolutely in character… to such an extent that when they’re finished, I’m lonely. I recently had a “big” birthday and the only thing I can think is “Oh god, never stop writing, because if you carry on writing you’ll hang on in there, to life, because it gives you a reason”.

PV: It’s that curiosity that we humans have that never stops. It’s what really keeps us alive and what feeds our soul as well, and I think one of the fascinating things about the quarantine is what people were sharing on social media was not about someone’s career or successes they had, it was about singing a beautiful song or writing a poem. We came back to that creativity, which was a gift of these really hard times.

SD: Yes, and I think that’s true of the Renaissance. As I’ve said, the Renaissance was a brutal time. There was a great deal of violence, there was a great deal of corruption; we’re wrong just to see it as some epitome of wonder and beauty because exactly the same energy force that created that, also created massive walls, created torture. There is darkness and light; you can’t just concentrate on one and forget the others. Somehow you have to plait them together.

Watch the video interview between Sarah Dunant and Paola Vojnovic, which took place on August 29.

Sign up for Paola’s newsletter to see more of these interviews (donations welcome): www.paolavojnovic.com / paola50122@gmail.com