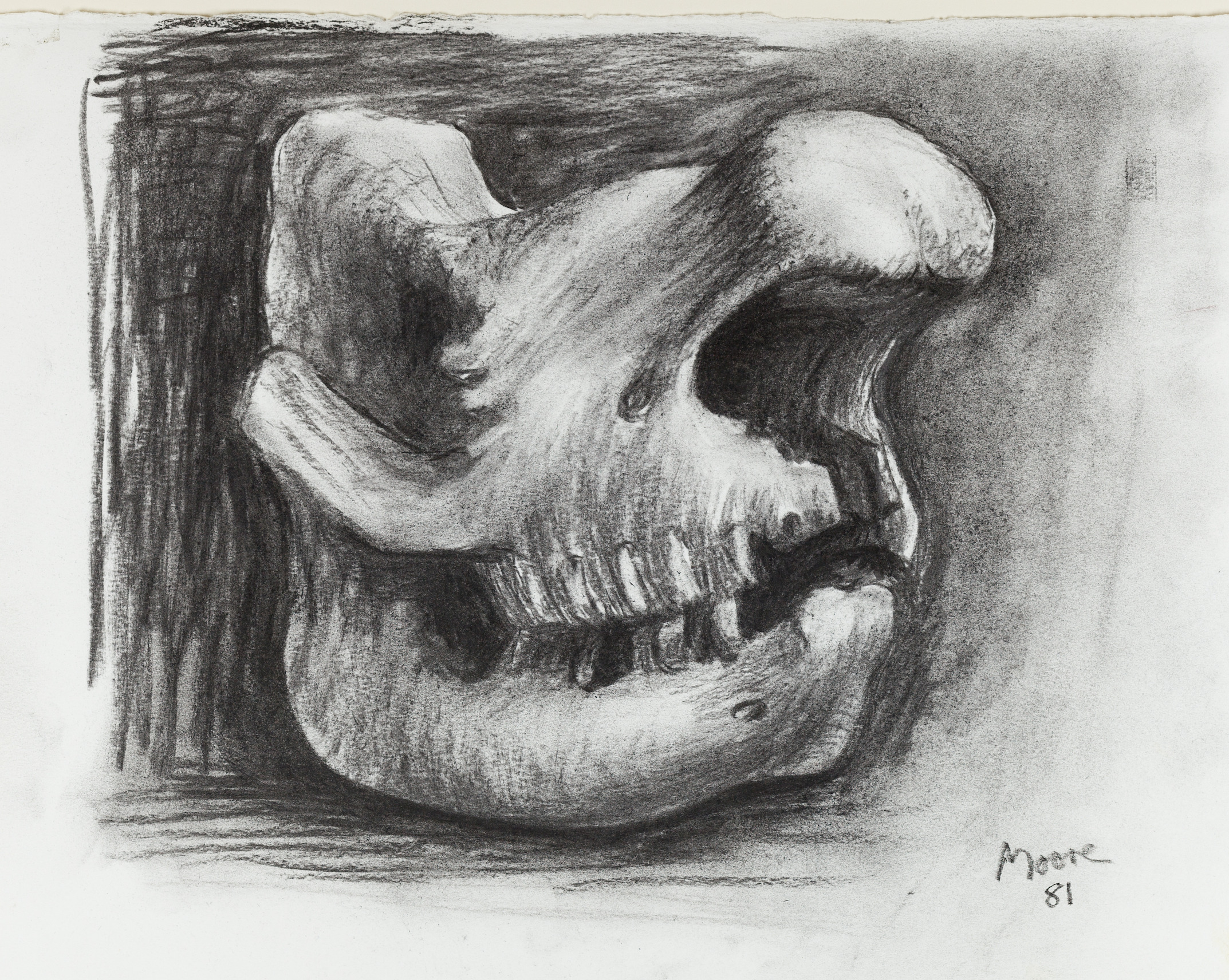

Henry Moore (1898-1986) viewed the display of his works at Forte di Belvedere in 1972 as the highlight of his career. His contemporary works juxtaposed with the Renaissance valley below shook the art world, the abstract figures marking a break from the staid canon. Now, almost 50 years since this pivotal moment, Florence’s Museo Novecento honours the prolific artist with an exhibition titled The Sculptor’s Drawing: Henry Moore, on display from November 13 to May 23. Curated by Sergio Risaliti, artistic director of the Museo Novecento, and Sebastiano Barassi, head of Henry Moore Collections and Exhibitions at the Henry Moore Foundation, the show varies from an elephant’s skull to footage of the artist, bringing Moore’s creative process to life in a highly anticipated and rare opportunity to see his ideas on paper.

Stone Figures in a Landscape Setting, 1935. Ph/ Sarah Mercer. Reproduced by permission of The Henry Moore Foundation

Jane Farrell: What is the significance of these works being exhibited in Florence?

Sebastiano Barassi: Henry Moore’s history with Florence goes back to the mid-1920s when he first travelled to Italy on a scholarship from the Royal College of Art designed for him to study the “Old Masters” such as Giotto, Donatello, Masaccio and Michelangelo. He fell in love with the art of Florence and subsequently visited Italy regularly. He started to work with a stone merchant in Carrara in the late 1950s and then spent every summer at Forte dei Marmi, buying a house there in 1965 that became his home away from home. He met many important figures who holidayed in the area like the sculptor Marino Marini and the poet Eugenio Montale. However, more importantly, he met the art historian and curator Giovanni Carandente, who organized the 1972 exhibition at Forte di Belvedere. He really felt that that was one of his greatest achievements, displaying his work at such a prominent site with all its history and tradition. With old age, travel became more difficult, but he gifted one of his most important sculptures, Warrior with Shield, to Florence, which is still on display in the Basilica of Santa Croce.

JF: What do you see as the most striking element of the exhibition?

SB: Something that has captured the imagination of people who have heard about this is an elephant’s skull alongside prints (etchings) made from Moore’s drawings of the skull. Moore loved to find inspiration in natural objects, which could be anything from seashells to pebbles he found on beaches and in the fields around his home in Hertfordshire. Over the years, he accumulated an extraordinary collection, some of which were gifts from friends. One of these was Julian Huxley, the secretary of the Zoological Society of London and first Director General of UNESCO. He lived in London and had an elephant skull, which he kept in his garden that he decided to gift it to Moore in 1968. Moore took it to his studio and we have those drawings on display. Another thing that surprises people is how media savvy Henry Moore was in terms of his generation. He was one of the very few living artists about whom a documentary was made at that time, some of that footage is going to be in the exhibition. It’s quite a nice way of introducing Moore’s voice and physical presence as it always feels like there’s an absence without the artist there.

Man Drawing Rock Formation, 1982. ph/ Henry Moore Archive. Reproduced by permission of The Henry Moore Foundation

JF: What’s the reason for your own personal interest in Henry Moore?

SB: I trained as an art historian in Italy and I moved to Britain over 20 years ago. Eight years ago, I joined the Henry Moore Foundation and my very earliest experience of art was the 1972 exhibition of Moore in Florence. I was only four years old at the time, but I have these vivid memories of these massive sculptures against the skyline of Florence and that imagery, which I never really thought about for many years, is the first memory I have of seeing any art.

JF: How do you see the role of a museum as having changed in light of recent events?

SB: People who feel threatened in their daily lives and livelihoods seek to stay grounded. They need to remain aware of who we are, our history and where we come from. These are all things that museums do very well. They present histories and preserve them for us, so that we can remain part of our trajectory or tradition, giving us grounding and certainty. It also gives us entertainment and distracts us from the challenges of everyday life.

Rhinoceros VII, 1981. Ph/ Nigel Moore, Menor. Reproduced by permission of The Henry Moore Foundation

JF: Henry Moore believed in the importance of drawing as a daily practice. I think that’s something many people can confirm, particularly now given how creative practices are sustaining us through a difficult juncture. What is notable about the drawings that will be on display?

SB: Moore referred to drawing both as a physical exercise and as a means to learn how to use your eyes and see more intensely. In drawing, he could test ideas that wouldn’t necessarily work in his sculptural work. Towards the end of his life, he had quite severe physical health problems and was essentially unable to make sculpture. However, he could continue to draw and he made nearly 1,000 drawings in his last two years.

JF: What do you see as the reason for Moore’s enduring popularity and what’s his particular relevance today?

SB: Moore speaks a universal language. His work is about the human body, something we all can relate to. It’s about archetypal figures that are images of humanity rather than specific human beings and that’s something that generally appeals. There’s also his slight abstraction that never goes too far, so the figure always remains recognizable and that’s also something that’s got great appeal. But most importantly, Moore had a power of humanity. In fact, his works were more popular in the aftermath of the Second World War, when he was very much at the centre of the programme of cultural exchange between countries that had been enemies during the war. The reason for his success was that he was speaking a language with which everyone identified and which didn’t have any particularly national connotations or political agenda. It was really about humanity and resilience and, in that sense, I think today more than ever those messages are relevant—that’s what makes Moore’s works interesting and attractive.

The Sculptor’s Drawing: Henry Moore

Museo Novecento, piazza di Santa Maria Novella 10, Florence.

On display until May 23, subject to Covid-19 regulations

See www.museonovecento.it for more.