- Piero Boni’s shop by Philippa Bogle

- Arnolfo Tower by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

- Il cielo in inverno Firenze 1998 by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

- Il Ponte Vecchio Firenze 1968 by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

- Piazza S. Spirito Firenze 1959 by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

- La Cappella dei Pazzi Firenze 1996 by Piero Boni. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

- Il Giardino di Boboli Firenze 1960 by Piero Moschi

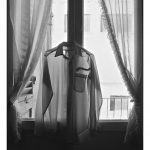

- Untitled by Piero Boni

- Mulberry Street, New York 1988 by Piero Boni

- Guendalina by Piero Boni

You could walk past Piero Boni’s tabaccheria near Ponte alla Carraia and think it was just like every other of the hundreds in Florence. But if you know a bit about photography, your eye might be caught by the racks of dusty, curling postcards outside.

Piero Boni’s shop by Philippa Bogle

Perhaps if the city was as crowded as usual I might have dismissed it along with the tourist traps selling fluorescent Davids, lined up like a Warholian nightmare. But Florence was quiet and I had time to kill, so I glanced as a local character went into the tabaccheria opposite. At that point, I felt compelled to cross the street for a closer look.

At best, I was expecting a couple of bearable views, but on scanning the racks of black and white postcards I realised these were of a much finer, more nuanced quality than the usual fare. At one euro, they were no more expensive than normal postcards, but as my pile of must-haves grew I had to edit them down again, brushing off the dust. One image, dated 1950, of a man clearly trying to pick up a well-dressed woman on the Ponte Vecchio, looked like a still from Roman Holiday; perfect to send to friends—an ironic nod to the not-quite-extinct Italian stereotype of catcalling and an exercise in the not-quite-obsolete art of writing postcards.

Other images were more subtle and interesting. I was drawn to some quiet still lives that reminded me of Czech photographer Josef Sudek. Others of the Boboli Gardens and a misty Arno had the pictorialist atmosphere of Edward Steichen or Alfred Stieglitz. Classic street scenes of Florentine shopkeepers or smokers in Santo Spirito were reminiscent of Henri Cartier-Bresson and André Kertész. All skillfully mastered the interplay of light and shade that characterizes Florence and that the black and white medium inherently amplifies.

Arnolfo Tower by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

I started matching up images to credits and one name, Piero Moschi, featured frequently in my selection. Surprisingly, his images spanned a 45-year period, the earliest dated 1952 and the latest 1998, a timespan in which the style—and technology—of photography had shifted radically, but these images had a timeless poignancy.

I wanted to buy them all, but fifty euro on postcards seemed excessive, so I settled on eleven and went inside to pay. The kindly shopkeeper, sitting behind a small counter surrounded by cigarettes and lotto cards, returned one euro saying the eleventh was free. “Molto gentile,” I replied, before abandoning my faltering Italian with a curiosity to learn more.

I commented how good the images were and asked about their provenance. He said many of the photographers had been his friends and then, almost in passing, that some of the images were his. “Which ones?” I asked excitedly. He showed me his name, Piero Boni, on many of my favourites: the cat scratching at a window; the couple staring up at a chapel ceiling like statues; an artist’s studio window with silhouetted glass bottles, framed in perfect asymmetry. I said they reminded me of Sudek. His face lit with recognition and we bonded over a love of photography. I explained I’d studied in Florence 30 years ago and my work had a similar aesthetic, with humans either absent or reduced to archetypal figures.

Il cielo in inverno Firenze 1998 by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

And then, Signor Boni explained that he wasn’t just selling the postcards, he’d published them. For over twenty years he had owned an art gallery in the same street, which had been shuttered after the last economic crisis. Now, aged 68, he’d been a tobacconist for ten years. He was selling the vestiges of his final print run: “I used to stock my postcards all across the city but,” he shrugged, “times have changed.”

And Piero Moschi? Boni told me he had discovered Moschi, a Florentine native like himself, in 1990 along with a trove of never-seen images from a lifetime photographing his beloved Florence, just sitting in a wardrobe. “He was too modest,” Boni said. “He would destroy his negatives after making one print!” The true passion of the amateur.

Boni added him to the roster of well-respected photographers he published, including Massimo Listri, Nicola Lorusso and Maurizio Berlincioni as well as Americans Lester Gediman (author of the Ponte Vecchio pick-up) and Rudy Burckhardt, whose work is in MoMA.

Il Ponte Vecchio Firenze 1968 by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

In 1997 Boni curated Moschi’s first exhibition, aged 77, at the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno: Piero Moschi’s Florentine Atmospheres – Florence in a hundred photographs 1942-1978. Renowned art historian Italo Zannier wrote the accompanying texts. Moschi’s images were not just fine works of art, but important documentation of Florence during that period since the 1966 flood destroyed much of the city’s archive. The show was a success and received nationwide coverage: La Repubblica called it a “homage to the great photographer” and reviewers praised the elegiac quality of the work, which captured “a nostalgia for a Florence that no longer exists”. Boni himself described Moschi’s photographs as “crisalidi silenziose” (silent chrysalises).

The exhibition also prompted a lively and perennial debate about how much the city had changed, due to the invasion of tourists and the Arno, a disaster Moschi found too painful to document. “The city needs to get back to its roots,” declared La Nazione: it seems Florence has ever been in a perpetual state of nostalgia.

When he died in 2009, Moschi bequeathed his archive to Boni, whose great wish (more than for his own legacy) is to find a permanent home for Moschi’s work, hopefully in a museum. Having revealed Piero Moschi to the world, he doesn’t want him to fall into obscurity again.

La Cappella dei Pazzi Firenze 1996 by Piero Boni. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

All the time we talked people called out “Ciao Piero!” or popped in for a lotto ticket. I wondered how many of his customers knew about his artistic past. “A few,” he said, self-effacingly. And does he still take photographs, despite working a seven-day week? “Yes,” he replied and showed me his iPad: over 14,000 images! I showed him a similar number on my phone and we nodded ruefully: it’s not a habit that you just give up. In the words of Piero Moschi to La Repubblica: “I work as before, like when nobody saw my photos.”

We couldn’t help shaking hands as we parted; we’d had a real-world interaction, one that simply couldn’t have happened on Instagram. As I left, I looked again at the racks of images and could clearly see one curatorial vision; this was still a gallery, albeit in miniature. Despite his modesty, Piero Boni was still an artist, but he had also become part of the street life of Florence, like one of the shopkeepers in his postcards, an infinity mirror of reflections.

Piazza S. Spirito Firenze 1959 by Piero Moschi. Photo courtesy of Piero Boni

My parting thought was how a single action by a photographer, to capture their vision and emotion in a fleeting moment, could ripple out across time and catch you in its wake, like a postcard delivered decades late. Just like the power of art resonates beyond the lifetime of its maker, regardless of his changing fortunes or those of the city that bore him.