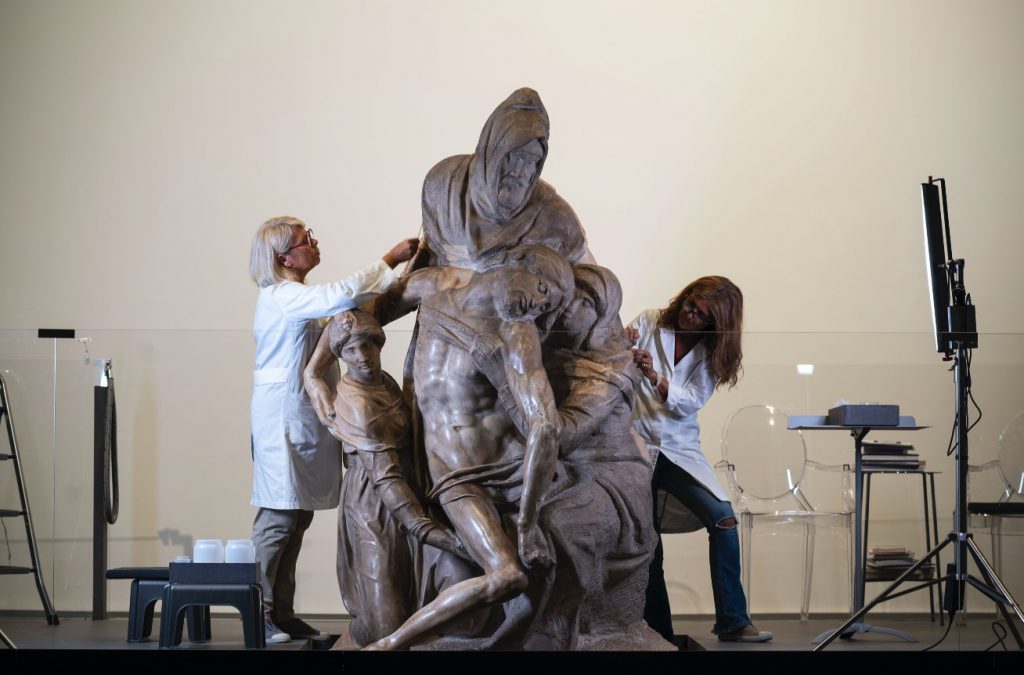

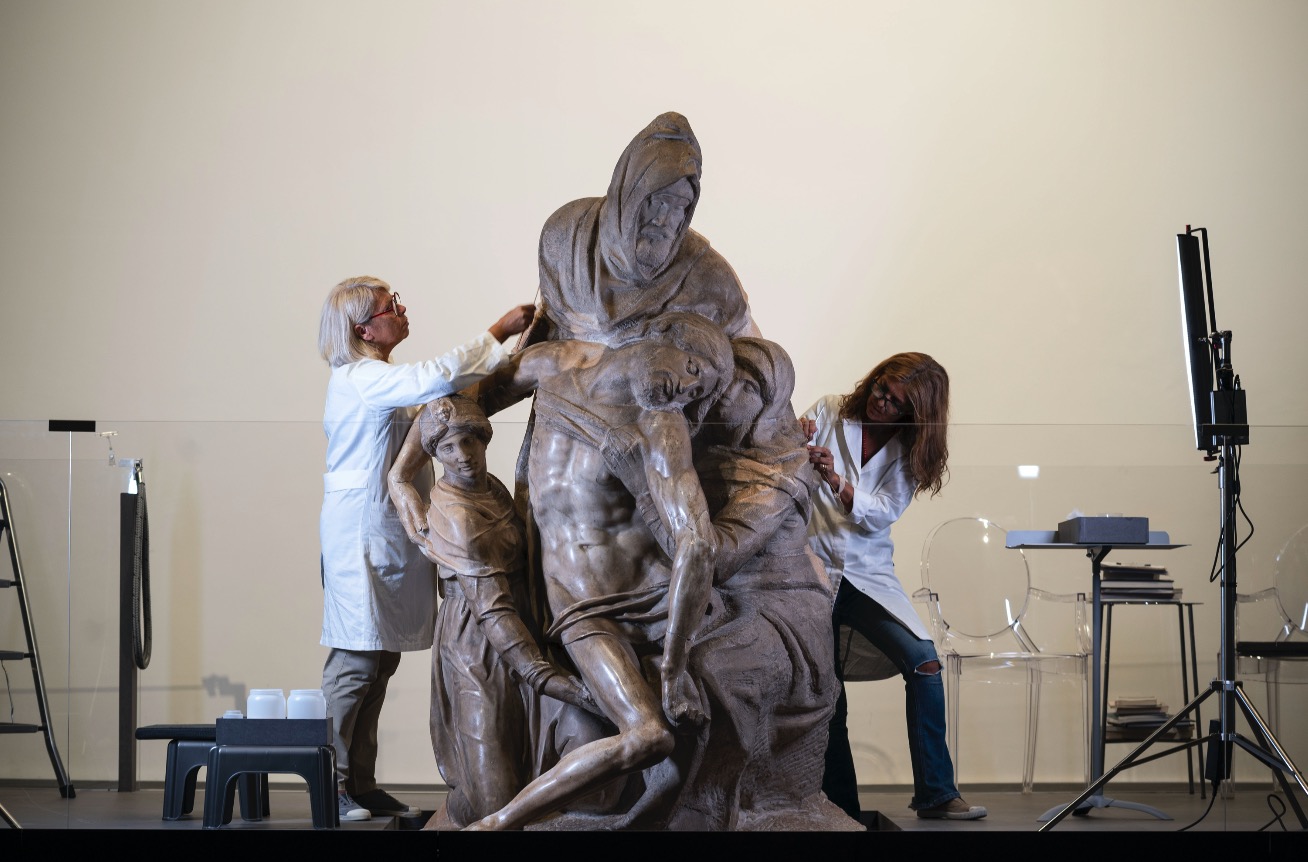

The lengthy restoration of Michelangelo’s Pietà has been completed at the Opera del Duomo Museum. Funded by the US non-profit Friends of Florence association, the restoration started in November 2019 and was interrupted several times due to pandemic restrictions. Otherwise known as the Pietà Bandini, the campaign provided a unique opportunity to explore the sculpture’s complicated history and the techniques that Buonarroti used to create the masterpiece.

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

Courtesy Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, photo Claudio Giovannini

One of the principal aims was to gain a balanced understanding of the work while removing the built-up of dust on the surface, which altered the viewer’s perception of the colour and sculptural quality. The final result reveals the intense beauty of what was perhaps Michelangelo’s most tormented artwork. The choice to carry out the restoration in an open-access site ensured that visitors to the cathedral works museum were able to follow the restoration in progress. Now, a decision has been made to maintain the raised platform used for the restoration until March 30, 2022, so that visitors can see the restored Pietà up close and from a singular perspective.

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

Courtesy Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, photo Claudio Giovannini

The statue’s four figures, including the elderly Nicodemus bearing Michelangelo’s face, were carved from a single marble block that stands over two metres high and weighs approximately 2,700 kilograms. Diagnostic tests revealed that the marble originated in quarries situated in Seravezza, in northern Tuscany, and not from Carrara, as previously believed. This is a significant discovery as the Seravezza quarries were owned by the Medici family and Giovanni de’ Medici, who would go on to become Pope Leo X, had instructed Michelangelo to use this particular marble to craft the façade of the San Lorenzo basilica in Florence and to open up a sea route to transport the raw material. How this huge block of stone was available to Michelangelo in Rome when he sculpted the Pietà between 1547 and 1555 nevertheless remains a mystery. What we do know is that Michelangelo was not remotely satisfied by the quality of the marble since it had tiny fractures that were impossible to pinpoint from the outside and veining that would suddenly reveal itself during the sculpting process.

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

Courtesy Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, photo Claudio Giovannini

The restoration has confirmed that the marble used to craft Pietà was indeed defective. In his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), Giorgio Vasari described the marble as “hard”, “full of impurities” and that it “sparked” with every strike of the chisel. The restoration unearthed various pyrite sections embedded in the stone, which were undoubtedly made from sparking when the marble was worked, in addition to countless micro-fractures, especially one on the front and back of the base. The theory is that, on encountering the fracture while carving Christ’s left arm and the Virgin Mary’s arm, Michelangelo was forced to give up on the project as it meant he was unable to conclude the commission. Another hypothesis is that Michelangelo, now in his later years and unhappy with the end product, decided to destroy the sculpture with hammer blows. The restoration, however, showed no evidence to support this theory, unless fellow sculptor Tiberio Calcagni erased the marks. This campaign can be regarded as the first time the Pietà has been restored, as historical sources do not state particular interventions in the past, apart from the statue’s “completion” by Tiberio Calcagni sometime before 1565. Over a life spanning more than 470 years and changing hands a multitude of times, the Pietà had only undergone routine maintenance that was never documented.

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

Courtesy Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, photo Claudio Giovannini

Tests were conducted in the lead up to the restoration, which provided key information about the sculpture and guided the process. No historical patina was found on the Pietà, with the exception of a few traces on the base, while the surface deposits were considerable, including a large amount of plaster, left over from the cast made in 1882, which had left a highly visible whiteness and excessive dryness on the surface. Wax had been applied repeatedly on top of the plaster over time to remedy the effect. The natural ageing of the wax, mixed with a build up of dust, especially in the folds of the clothing, in clear contrast with the lighter undercuts, gave the surface an amber-like and unbalanced colour effect.

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

Courtesy Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, photo Claudio Giovannini

Based on these results, the decision was taken firstly to go ahead with test cleaning, in order to identify the most suitable method, and then to start the restoration from the back, where most of the deposits were located. Cotton swabs dipped in lukewarm deionized water were used as a non-invasive, gradual and controlled technique. To remove the wax on the surface, both widespread and dots that had come from dripping candles on the main altar, which had stayed on the back of the statue for 220 years, the choice was made to clean the statue with water and a scalpel in the most complex instances.

The Opera del Duomo Museum is open daily from 10.15am to 5pm. Closed every first Tuesday of the month. Green pass required.

History of Michelangelo’s Pietà

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Firenze.

Courtesy Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, photo Claudio Giovannini

The Pietà dell’Opera del Duomo is one of the three such statues sculpted by Michelangelo. Unlike the other two, in the Vatican and the Rondanini in Milan’s Castello Sforzesco, Christ’s body is held not only by Mary, but also by Mary Magdalene and elderly Nicodemus. The reason why the artist to carve his own visage on Nicodemus is explained by Michelangelo’s peers, the biographers Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi, whose writings inform us that the sculpture was originally meant to sit on the altar of a Roman church, at whose base the artist wished to be buried. Michelangelo is believed to have carved the Pietà dell’Opera del Duomo between 1547 and 1555. He did not finish the work and gave the statue to his manservant Antonio da Casteldurante who, after having it restored by Tiberio Calcagni, sold it to the banker Francesco Bandini for 200 ecus. Bandini had the sculpture placed in the gardens of his Roman villa in Montecavallo. In 1649, the Bandini heirs sold the Pietà to Cardinal Luigi Capponi, who had it moved to his palazzo in the Montecitorio and four years later to Palazzo Rusticucci Accoramboni. On July 25, 1671, it was sold to Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, through noble middleman Paolo Falconieri. After a further three years in Rome, due to transportation issues, the Pietà was shipped from Civitavecchia to Livorno in 1674, and from there along the Arno to Florence, where it was placed in the basement of San Lorenzo Basilica. It would remain there until 1722, when Cosimo III had it housed to the rear of the main altar of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral. In 1933, the sculpture was moved into Sant’Andrea Chapel to give it more visibility. Between 1942 and 1945, to protect it from the war, the Pietà was returned to the Duomo. In 1949, the work was moved back into the Sant’Andrea Chapel, where it stayed until 1981, when it was moved into the Opera del Duomo Museum in order not to distract from the worship due to the high number of tourists who wished to see it as well as for safety concerns. (The Vatican Pietà had been vandalized in 1972.) Towards the end of 2015, in the new Opera del Duomo Museum, the Pietà was positioned in the centre of the Tribuna di Michelangelo, on a plinth reminiscent of the altar for which the sculpture had been meant.