“Nobody only loves masterpieces,” art collector extraordinaire Roberto Casamonti once remarked, his words projected onto the whitewashed walls of the uplifting gallery that carries his name in piazza di Santa Trinita. “And thank goodness for that, I’d like to add. Masterpieces are discovered by cultivating with daily passion the desire to collect.”

Born in Ponte a Ema, just outside Florence, the founder of Tornabuoni Arte fell in love with the art world when he was just ten years old. In 2018, he purchased the first floor of the enthralling Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni, a neighbour of the Salvatore Ferragamo flagship store, and set about sharing his private collection of paintings and sculptures dating from the early twentieth century to the present day. The first half (up to the 1960s) was exhibited upon the gallery’s opening, while the second half (from the 1960s to now) was hung back in May 2019.

Blame lethargy, the pandemic or myriad other distractions, but I only made it back to wonder at the revised collection over the holidays. It was the perfect moment. Any winter blues were assuaged by the little-known Boettis, Pomodoros, Basquiat and Mirò, which challenge and inspire in the stately sixteenth-century building designed by Baccio d’Agnolo, otherwise known as the palazzo Per Non Dormire (“lest we sleep”). Indeed, the Bartolini Salimbeni coat of arms consists of three poppy pods wrapped in tape and clasped together with a ring, emblazoned with the sleepless motto. There’s also an anecdote, explained on the table by the ground-floor entrance, about the family’s progenitor, a silk merchant, who made a fortune by treating his competitors to a banquet and drugging the wine with opiates, so as to obtain a monopoly. The likes of Henry James and Herman Melville also stayed within these walls when the palazzo served as the Hotel du Nord from the 1840s onwards.

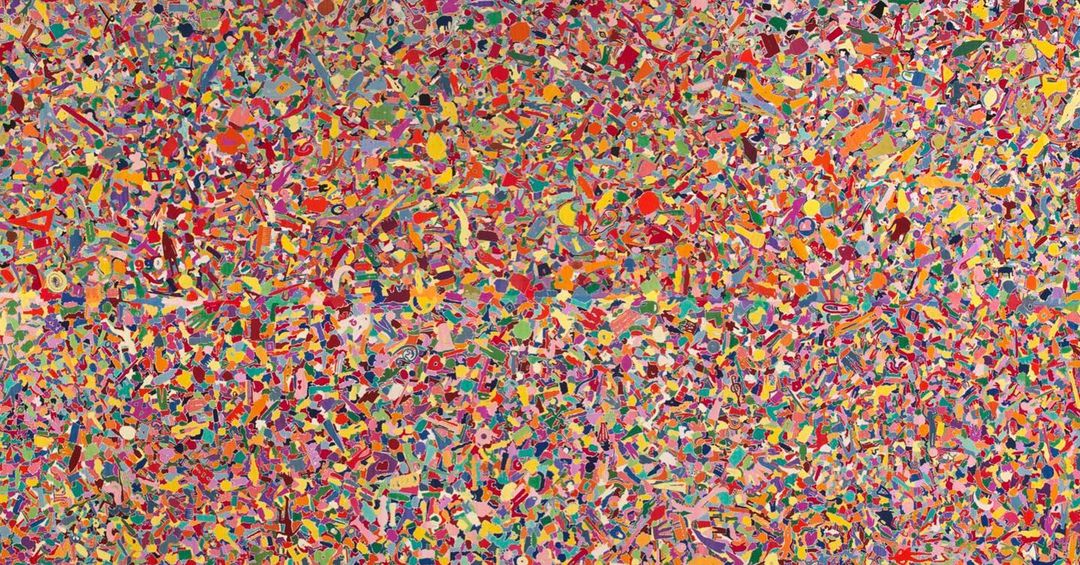

Alighiero Boetti, Tutto, 1992-94

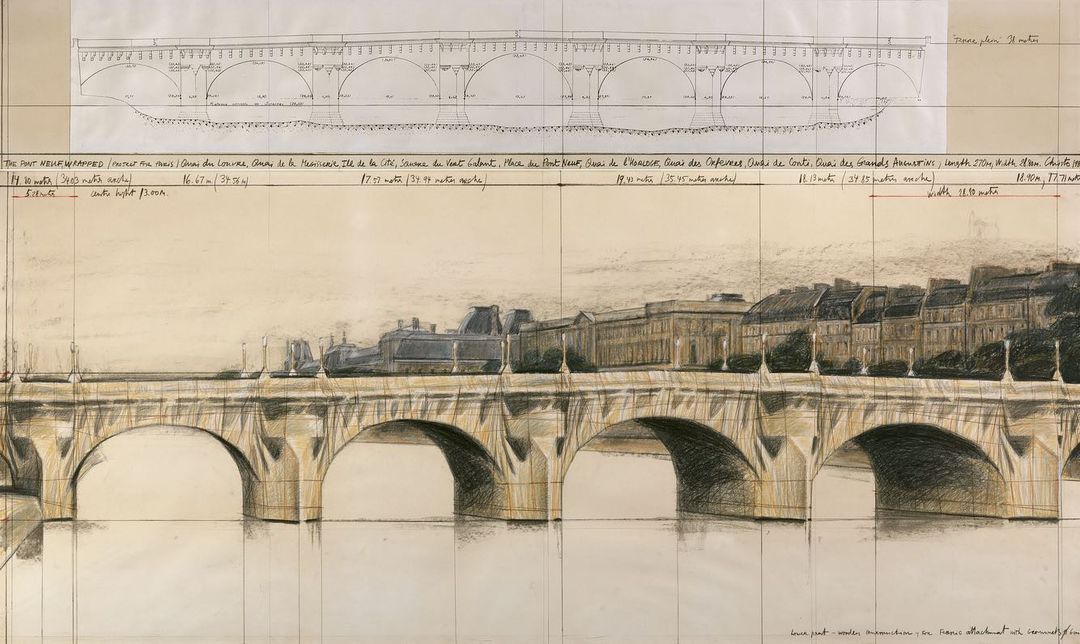

A grooved Arnaldo Pomodoro copper sculpture greets art lovers by the glass door into the collection as Alighiero Boetti’s 1975 embroidered Mappa (L’insensata corsa della vita) demands our attention on the right-hand wall, inciting impatience while handing over a ten euro banknote as if in a self-justification of the piece. An interactive corner of playfulness comes from Michelangelo Pistoletto’s mirrored works, while Jannis Kounellis’ take on a rustic workspace equipped with an oil lamp balances out the jollification and Penone’s walnut and bay leaves in chicken coop wire adds a caginess to the proceedings. All this feels academic compared to the 255 by 595 cm cloth embroidery above the pietra serena hearth. The world outside pales into insignificance for a good 25 minutes as I fall into the intricacy of Boetti’s Tutto 1992-94. Human attributes and animal forms coexist with musical notes, glasses and zodiac signs in this jumbled and joyful outpouring by the Turin-born conceptual artist and member of the Arte Povera movement. But then my gaze shifts left and office-related thoughts flood back front and centre (to me) in Boetti’s blue pen-on-paper work, alphabetized and apostrophized. It verges on a beautiful affront to an editor: the curly punctuation implemented out of context, like the absence of the genitive case. The enticing collection continues beneath the coffered wooden ceilings and patterned terracotta flooring, dotted with gilded and grey cushioned fauteuils and divans. Christo’s 1980s plans to wrap Paris’ Pont Neuf ups my concentration span by several minutes, an engaging look behind the scenes of the revelatory environmental artwork that drew at least three million onlookers in a fortnight in September 1985. In a small side room, performance art warrants its own focus with provocative remembrances of Marina Abramovic’s Banging the Skull, a coloured print from the Balkan Erotic Epic series, and Vanessa Beecroft’s sexist or not sexist, naked but boot-wearing VB 45 performance, alongside a hypnotic video, The Encounter, by Bill Viola. The “James Dean of modern art”, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s bold, yellow, acrylic Untitled (1984) speaks to the human condition alongside equally unnamed works by his peers: Keith Haring, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol.

Christo, The Pont Neuf Wrapped (Project for Paris), 1980

The Collezione Roberto Casamonti is so discreet that there’s hardly anyone there. Alone, masked, breathing in this art and architecture is an antidote to our trying times. Masterpieces or not, we need these works in our lives.