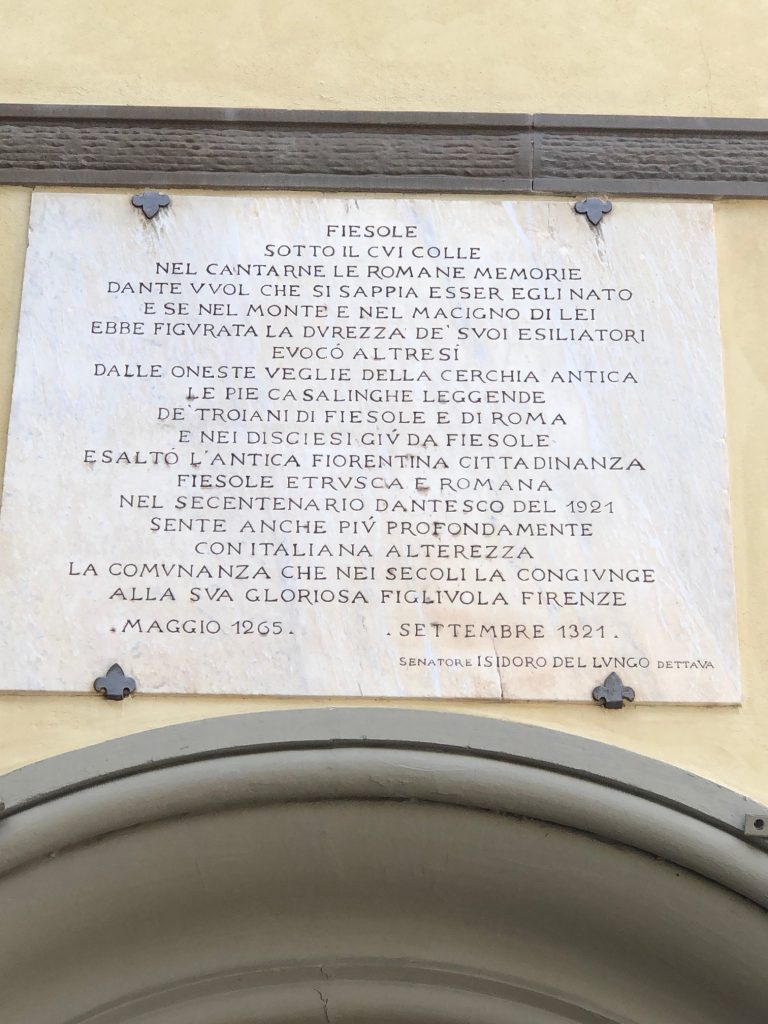

Every house tells a story. This is especially true in Florence where people might be living in them for a thousand years or more. The house where I live overlooks the gentle basin of Florence and had its first stone laid in 1120. A first part was completed at that time, whereas a second section was annexed 400 years later. In between, a little cappella was added with frescoes dating from the early 1300s. Ours is only the sixth family to “pass through” these storied halls. The first family were the Compiobessi, a family from the town of Compiobbi just across the river, who were likely determined to get away from noisy neighbors, and so built a fortress-like structure up on the hill. After that came the Salviati for some 400 years. I couldn’t help but wonder if they had the Pazzis up for tea and together conspired to do in the Medici. After them, there was a family by the name of Phil Neri, who plastered their name on every door frame, then another family, and then the Pacchiani-Quentins beginning in the early 1800s, who in 2017 entrusted me with this 900-year-old house. In Florence, I don’t really feel like a property “owner”, as much as a gatekeeper and link to the next generation of gatekeepers for the time I am lucky enough to be so.

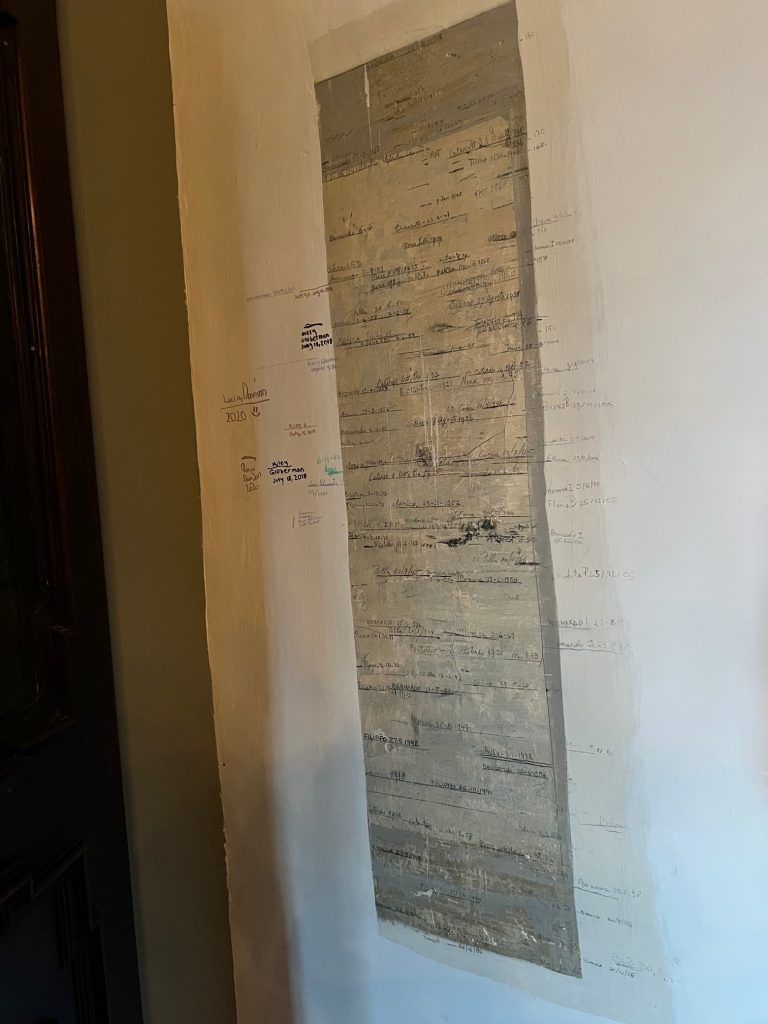

A building on the property, a little farmhouse of sorts, now a series of music rooms, has an inscription on one of the interior arches. Costruito – 1855. Built in 1855. Behind one salon door in the main house there is a “measuring wall”, where children’s heights have been memorialized over the centuries and previous layers of ancient frescoes can be seen. While this particular “measuring wall” begins with the previous family in the early 1800s, there is a gap in the early 1940s when no names were added. On the farmhouse wall, there is a painted inscription: 1944. Having become friends with the previous family who resided within these four walls, I couldn’t help but ask.

“What happened here during the war?”

Family members who had been here as young girls told me that they remember how one day, in the early 1940s, a neighbor rushed to warn them that they had better take whatever they could and get out of the house immediately. Rumor had it that Germans were coming and they wanted the house. They remembered packing a few belongings and leaving their family home, the only home they had known. Life was more precious than any walls could ever be. Other neighbors had shared that Nazis took over the house and made it their local headquarters. They told stories of a Nazi standing guard on the rooftop tower with fascists on one side of the house and partisans on the other, shooting at each other. The guard on the tower was caught in the crossfire and tumbled to his death. There was a rumor that Nazis were burying their dead underneath the stone alongside the chapel. There is no evidence, however, that this was the case, although neighbors did speak of Nazis tossing deceased Italians from the property into the ravine. Family members told me that, after the war, they were able to return, restore the home as best they could, and in the 1950s they were able to celebrate weddings, births and a return to life. I have always wondered if walls keep their stories, these pieces of humanity, and whether both the best and the worst become forever embedded in their stones.

For me today, this home is one of laughter, love, music and storytelling, especially that of Italian heritage, as well as my own, a Jewish one. This coming summer, I shall host the wedding of a very special cousin, and I suspect it will be the first time on the property that a chuppah, a Jewish wedding canopy, will welcome newly joined lives. I have asked several Florentine artisans to take part: the esoteric Aquaflor perfumerie for scents and flowers; the chef of Ruffino and the Le Tre Rane restaurant, Stefano Frassineti, to do his culinary magic; the Rabbi of Florence’s majestic Synagogue, Rabbi Gadi Piperno, to perform the ceremony; musicians from the Maggio orchestra and more. While it is a personal event (I’m definitely not in the wedding business!), the opportunity to bring together so many friends is a way to bring light into a home. One must remember a dark past so as never to repeat it, but bringing forth light is what one must do. To “live in light” is the goal. It always seems to me that assembling people who love art, music and beautiful things is a way to enhance the light. And here in Florence, a city of art and artists, there are so many who love this kind of beauty that being together at such gatherings is a regular joy. One such gathering happened in our first “lockdown break” in the summer of 2020.

It was a time where we were able to have meals and visits outside, and so I invited some neighbors for dinner on the terrace. At some point, I was asked to share the story of the house. It was then that my neighbor, Daniel Graves, founder of The Florence Academy of Art, the world-class training ground for fine artists, asked if any of us knew the story of the “three martyrs of Fiesole”. In the summer of 1944, around the same date that we were having dinner, August 11, three young Carabinieri were hiding in the Teatro Romano, the 3,000-year-old amphitheater in the hills of Fiesole. They had been secretly providing ammunition for partisans, hiding the arms in the gardens of their barracks, and the Nazis had discovered that this was happening. Word went out that if these military officers did not give themselves up immediately, the Nazis were going to kill ten Italian civilians as “payment”. This was the law at the time: one German life taken (or one infraction) was paid for with ten Italian civilian lives. Ten civilians were rounded up and held at the Hotel Aurora on the main piazza in Fiesole. The Monsignor of the church next to the Teatro Romano was alerted and went to seek out the Carabinieri. He found them in hiding. They were to give themselves up and likely would have to serve the Nazis. The young Carabinieri were overheard as having said that they would not have been able to live with themselves if they were to be responsible for the deaths of ten civilians. The chief of police was witness to all this, and he was the first to give himself up, telling the Nazis that the three officers would follow suit. The three spent some time considering their futures. Later that day, on August 12, 1944, they gave themselves up. One hour later, the three Carabinieri, just 22, 22 and 25 years old, were executed in front of the ten hostages. The hostages were held for another three weeks.

We were speechless. The courage of these young Italian men! From where does such courage, such honor, come from? I can only imagine that everyone around that table wondered what we would each have done in the same situation. These are not the events of the imagination. They happened right around from where we were sitting a little less than 80 years before.

The story of the three martyrs that Daniel shared has had a lasting impact. I couldn’t help but wonder what I would have done. I thought about that time between being given the opportunity to give oneself up and save ten lives, or to run and save oneself. What goes through a person’s mind when faced with the choice of one’s own life or the lives of others? I asked Claudio Bertini, who runs the summer cultural programming, known as Estate Fiesolana, at Fiesole’s Teatro Romano if he would be amenable to a new musical theatre piece, titled Eroi, una storia vera (Heroes: A True Story), based on the story of these three martyrs to play out exactly where the real events happened. And so, this coming summer, the story of the three martyrs will be told in musical form in a world premiere on July 25, imagining how these young heroes viewed their futures and what choices they had to make. To honor the memories of these courageous young Italian men in song will be the honor of a lifetime.

Holocaust Remembrance Day

In 2000, Italy enacted a national law to call for the marking of a Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27 of each year. There is programming, gatherings, school offerings and more. This year, commemorative events will take place on Friday, January 28, as the election of the new Italian president falls on the 27th. Details about programming throughout Italy can be found here.