When Florence was the capital of Italy between 1865 and 1875, my great great aunt Janet Ross moved to the city with her much older husband, Henry Ross. Aunt Janet was a writer, following in the footsteps of her mother, Lucie Duff Gordon.

In 1888, Henry and Janet Ross acquired Villa di Poggio Gherardo, near Settignano. The house was reputed to have been the setting for Boccaccio’s Decameron. There, Janet held a Sunday salon where writers gathered. They included George Meredith, who had been in love with her, and, later, Norman Douglas. She found the Villa Viviani for Mark Twain and they became close friends. He would drop by Poggio Gherardo almost every day. In 1890, following the death of her sister-in-law, Fanny Duff Gordon, Janet adopted her 16-year-old niece, Lina, who refused to have anything to do with her father, Sir Maurice Duff Gordon. (He had been forced to sell Fyvie Castle after his reckless extravagance and elopement with his wife’s best friend.) Lina, my grandmother, moved from her convent school in Paris to live with Aunt Janet in Florence.

Lina followed Aunt Janet in the family tradition of women writers. Her relations with her aunt, however, were not improved when she fell in love and married the painter Aubrey Waterfield. As an undergraduate at Oxford, he had walked over the mountains from Portofino and became entranced by the Fortezza della Brunella, near Aulla, at the northern end of the Garfagnana Pass from Lucca. Much to Aunt Janet’s disgust, the young couple went to live there in Bohemian austerity. It was said that because of the beauty of its position, they had all the luxuries of life and none of the necessities.

During the First World War, the Italian government took over the castle while Aubrey served with the Northants Yeomanry, and Lina, with their young children, Gordon, John and Kinta, returned to live with Aunt Janet. Working as a journalist, Lina was disturbed to find that they faced a barrage of anti-British propaganda from German sources. Encouraged by the British Ambassador in Rome, Lina went to London to see John Buchan, Head of the War Propaganda Bureau, to obtain support in setting up The British Institute of Florence. With official support and the help of generous Florentine friends contributing to a most impressive library, The British Institute of Florence started life, and Lina was later awarded an OBE for her role in its creation.

After Aunt Janet’s death, Lina was the Observer correspondent in Italy until she was sacked by James Garvin, the editor, a great admirer of Mussolini, for her anti-fascist views. When war came in 1940, she and Aubrey escaped back to England. In their absence, Poggio Gherardo suffered considerable damage and was turned into a prisoner of war camp after the German retreat. Their adjoining neighbour, Bernard Berenson, proved a great help, repaying Aunt Janet’s hospitality when I Tatti was being transformed all those years before.

As a family, we stayed at Poggio every summer until Lina was forced to sell it in 1952 as a result of having to pay double death duties and repair the wartime damage. I was too young to have any clear memories of the house, although I do have unreliable images of going down to I Tatti for lunch with Berenson.

In later years, as a teenager and a young army officer, I loved returning to Florence to see friends, often staying with members of the Corsini clan. The link had begun in the 1880s between Aunt Janet and the parents of ‘Pio’, (Don Tommaso) Corsini. I remember as a child how he worried my mother when he showed me how to fire flaming matches from a toy cannon I had brought down to dinner. Years later, he said to me after a lunch at the Palazzo Corsini al Prato that a family friendship over so many generations almost made us closer than relatives.

Later, after I left the Royal Hussars to become a writer, in the family tradition, I was greatly encouraged by Iris Origo, with whom my uncle, Gordon Waterfield, had been in love. This showed great foresight on her part, since there seemed little to be optimistic about during my early attempts at fiction. Things only took off when publishers persuaded me as a former officer to switch to the history of war. Having grown up in the post-war years, I was fascinated by the way the Second World War continued to dominate our culture and memory. This became my career for the next 40 years and sadly left me very little time for trips back to Florence.

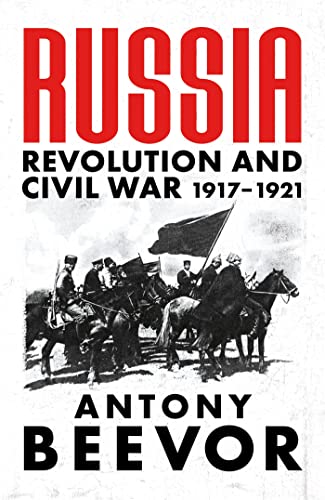

My latest book, Russia – Revolution and Civil War 1917-1921, took half a dozen years of research, mostly by my wonderful colleague of the last 28 years, Lyuba Vinogradova, since I am not able to return to Russia due to facing a possible prison sentence of five years. The book appeared last year soon after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, no doubt one of the many questions which I will be discussing with Simon Gammell on the evening of Thursday March 23 at The British Institute.