When Luisa Vertova died in 2021, Eike Schmidt, director of the Uffizi Galleries, said that “a great art historian has left us”. She had contributed “decisively to the knowledge of our collections.”

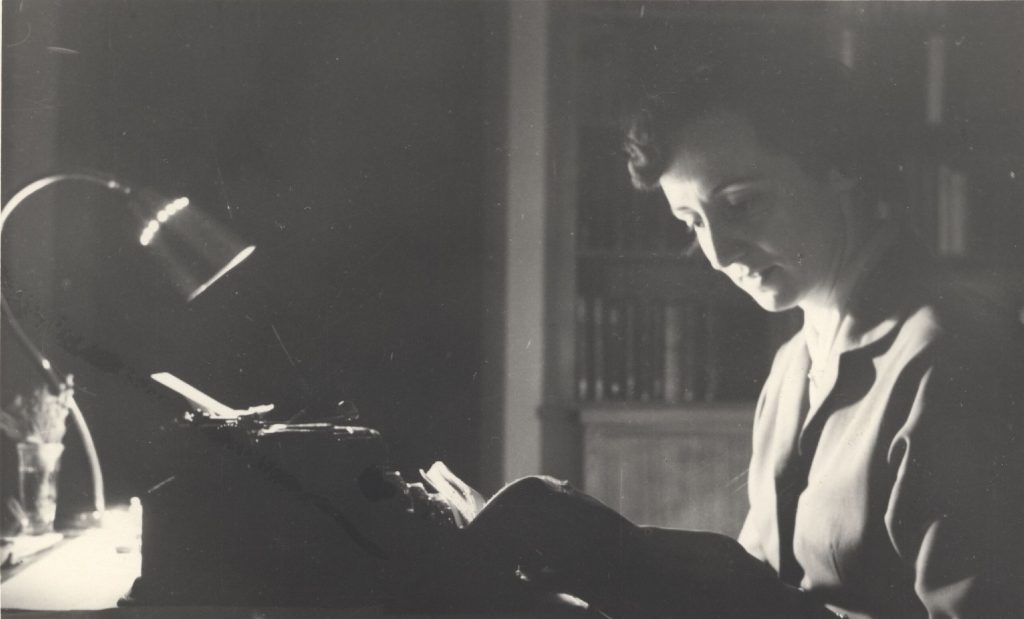

If you climb the 95 stone stairs in a medieval apartment building in Florence’s centro storico, you’ll enter the apartment of Luisa Vertova. (The many stairs might also explain her longevity: she was nearly 101 when she died.) The studio at the top of the building, where Luisa did much of her work, with views of the Duomo from the terrace, feels like an eagle’s eyrie—and Luisa did have an eagle eye when it came to her expertise in Old Master paintings.

Luisa Vertova was born in 1920 in Florence to an ancient Bergamasque family and grew up in an intellectual environment. She wrote that “it was normal in Florence for 15-year-old girls to abandon their studies to devote themselves to finding a husband.” Serious, academic Luisa had no interest in this fate.

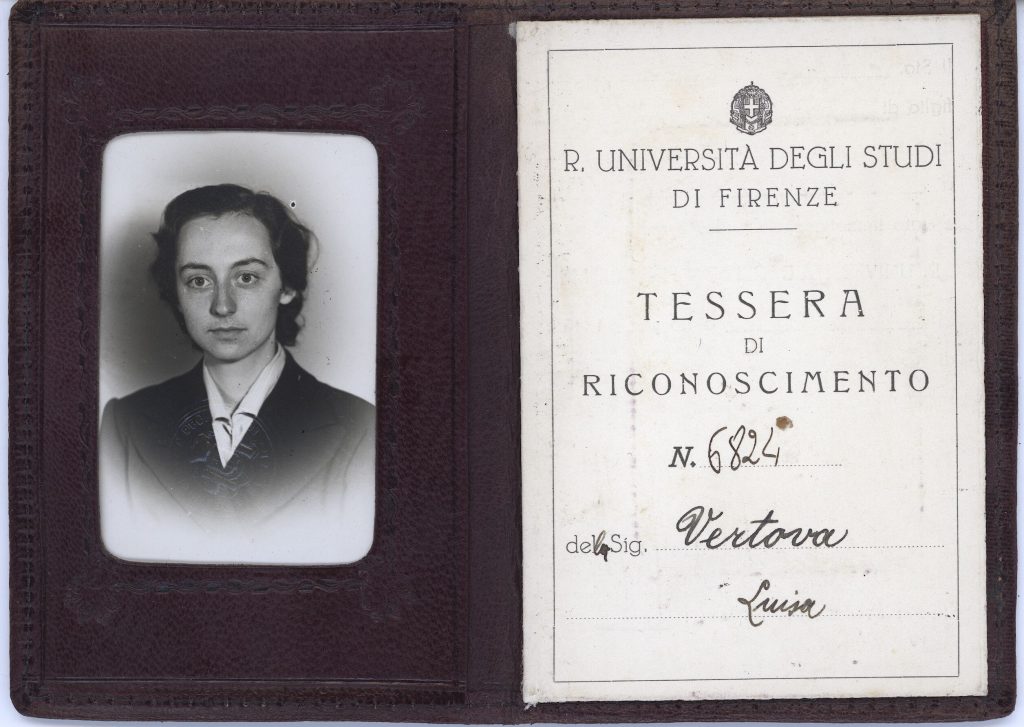

She spent World War II studying Classics at the University of Florence. Throughout the German occupation, she had several too-close-for-comfort encounters with Nazi forces. She wrote that these were “years of hunger, anguish, squalor. The empty Uffizi, the doors of the Baptistery covered in sandbags, the university meals for off-site students reduced to cat’s lung in black sauce…”

She won a scholarship to study abroad, but for Italians during wartime, “abroad” was limited to Hitler’s Germany: not an appealing prospect. The Marchese Piero Fossi, an intellectual friend of her father, convinced her to remain in Italy. Knowing of her interest in art, in 1943 the Marchese introduced her to Bernard Berenson, the celebrated art historian. A Jewish American, Berenson was held under house arrest at his Villa I Tatti in Fiesole for the duration of the war, the gates guarded by soldiers.

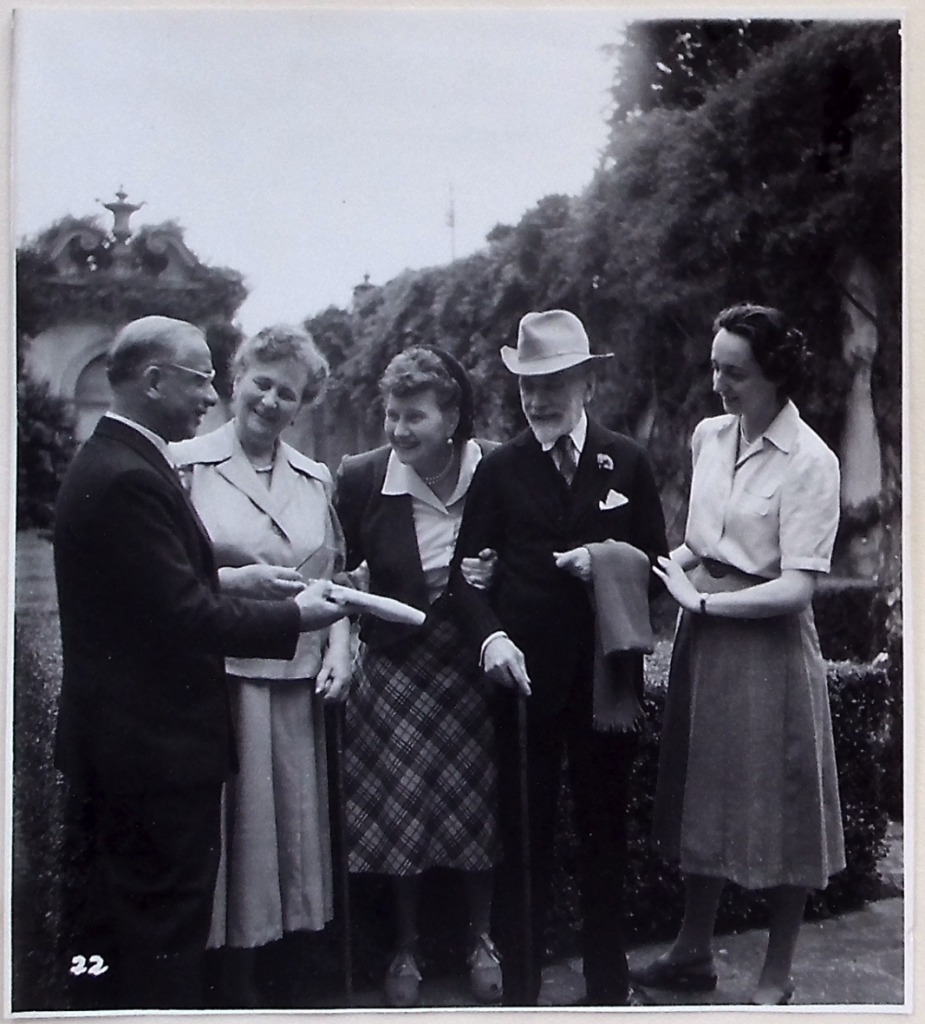

In 1945, when they met again, Berenson was concerned about Luisa’s health: she was slender to the point of malnourishment from wartime deprivation. He invited her to his home near Vallombrosa to heal, and when she’d recovered, he asked her to live and work at I Tatti. Luisa became Berenson’s researcher, translator and curator of his famous ‘Lists’ of Italian Renaissance paintings and worked for him until his death in 1959.

As a Fulbright Scholar, she visited the US in 1954, touring museums and art collections from coast to coast. Her letters to Berenson and friends are a delicious mix of gossip, social history, serious art and perceptive descriptions of America. She found “an assembly of forgeries” at the Fine Arts Gallery in San Diego and dreaded the “fireworks” of combining paintings and high society in New York City. Of travel in California, she wrote, “The Sierra Madre could not look more Italian. The groves of olive trees at San Bernardino reminded me of Formia…I feel almost at home. Almost!”

However, it was not all work at Villa I Tatti. It was a highly social environment. Guests included curators, academics, artists, Hollywood stars and shy young men just down from Oxford, who hoped to learn more about art from “il maestro”. One such visitor was Ben Nicolson, the son of Vita Sackville-West and Sir Harold Nicolson, now perhaps best known for their gardens at Sissinghurst Castle in England. Ben Nicolson’s time at Villa I Tatti was transformative, and his friendship with Berenson was to be lasting. He also became Luisa’s husband: the two were married at the Palazzo Vecchio in 1955.

Luisa found life in London difficult. 1950s Britain was no place to be a professional woman, especially a foreigner. Luisa experienced hostility, even in shops such as Harrods, where staff would approach her Italian accent with withering put downs. Many of Ben’s clubby intellectual circle of friends were also dismissive, preferring the company of men.

Carl Brandon Strehlke, curator emeritus of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, commented on this period of history. “Around 1950, Bernard Berenson said to a young woman who told him of her wish to be an art historian that many men would stand in her way. This was no more true of Luisa Vertova and her career in the 1950s and 1960s. It was the ‘Mad Men’ era and she often had to fight to get full recognition.”

After her marriage with Ben Nicolson broke down, largely due to what he referred to as his “congenital homosexuality”, Luisa returned to Florence where she continued to publish books and articles, and later worked as a senior consultant on Italian art for Christie’s. While Luisa might have had to “fight” to get full recognition, she did achieve it. Fondazione Zeri, the specialist art historical research department of the University of Bologna, recently held a symposium “Per Luisa Vertova”, celebrating her life and significant legacy.

The bulk of Luisa’s collection of writing, books, catalogues, photographs and correspondence have been generously donated by Luisa’s daughter, the author Vanessa Nicolson, to the archives at Villa I Tatti (now The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies), the Fondazione Zeri and the Centre for Conservation, ‘La Venaria Reale’, in Turin. All can be accessed by scholars and researchers.