April is naughty and sweet. On its very first day, jokesters look for

‘fools’ who fall for harmless stunts. Afternoons get sleepier and the sun

suddenly obeys the mandates of Daylight Saving Time, which Italians refer to as

l’ora

legale.

The thought of the ‘legal’ hour makes me as happy as

the day is long. First, there’s the pure pleasure of leisurely evening walks or

gelato chats in late afternoon. And then there’s the word-thrill for the

language geek in me: the phrase ora

legale implies that

time is ‘illegal’ in Italy for virtually half of the year.

April comes

with outdoor weekends and the newfound desire to paint one’s toenails and walk

somewhere in open-toe shoes. State museums turn magnanimous and dedicate an

entire week to welcoming the ticketless. Inside, museums are never as

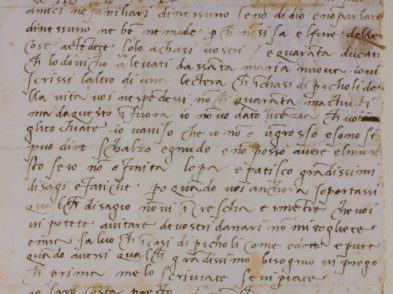

labyrinth-like as the signs posted outside suggest. Leonardo’s journals make

for easier reading. ‘Closed the second and fifth Tuesday of each month. Monday

afternoon closed, except for the first and fourth Monday in winter. In summer,

open only the fourth Monday. All pre-festive days excluding Saturdays are half

days.’ The exceptions could fill this entire magazine.

In Italy,

timetables are much like Tablets of the Law. If you’re feeling guilty about

something, its schedule signs will make you feel like punishment is more than

well deserved. To see what I mean, stand at the entrance of your neighborhood

park this weekend. Most likely, you’ll find that it’s open from 8:15am to

5:30pm in October and February. November and December have dibs on different

hours. The weeks couching Christmas deserve special treatment. In March the giardino gates stay unlocked one hour later than they did

before the Solstice. With the event of l’ora legale, schedules adjust to accommodate the height of the

sun in the high heavens. Potremmo

anche risolverlo così: before going to the park, say una pregherina that the gates will somehow swing open upon your

arrival.

Once you’re in,

all is well. Overdressed children are warned by over-anxious grandi who may as well hang on the monkey bars themselves

for all the instructions they give on how to avoid minor injury. Elderly ladies

brave the breeze. Older men agree on how bad the Russians had it in World War

II and wives of all ages speak of ironing pajamas. If you are expat and at all

smart, you will not even engage in the pajama-ironing debate-primarily because

it’s not a debate at all. So, rather than making enemies by piping up, ‘Who has

time to iron a nightgown?’ I’d suggest you limit your cultural queries to time

alone.

In Italy, time

possesses ultimate freedom. A hurried tyrant who always has the last word, il tempo è tiranno. An elderly physician who doctors

wounds and makes memories as cherry-sweet as healing cordial, il tempo è gentiluomo. Yet, no matter the Italian

insistence on posting every schedule variable known to algebra, time in Italy

does not often obey its bridle.

This even goes

for its tiniest increments: un

attimo, un attimino, un minutino solo, un secondino escape all forms of capture. The fact that the

country’s natives suggest something will be done in a ‘little second,’ implies

that the term is not, in fact, an unbiased unit of measurement. It’s expandable

and therefore far more expendable than the mere unaltered second used in the

English-speaking world.

A casa mia, time ranks high in causes of

multicultural misunderstanding. In other words, it’s high up there on our list

of theories why bicultural relationships need negotiation. Filippo and I agree

that most differences are habit-based. Like how Italians feel no guilt about

eating cookies for breakfast. How they see wild-roaming animals and fantasize

about how the critters would look roasted and carved on a plate. The national

conviction that floors should be waxed frequently. That the digestive process

is an enthralling topic. That to be worthwhile, shoes must cost at least 150

euro. That a smile means something other than it means. And the list goes on.

At the top of it, there’s il

tempo-il benedetto tempo-that’s not the same around the globe. ‘Early,’‘late,’ ‘right now,’ ‘in

a minute,’ ad una certa ora,

tra due minuti: these are

relationship mines left waiting in a potentially explosive field.

‘The problem

is,’ Filippo protests, ‘you really believe that time can be captured in a

clock.’

‘I do not.’

‘Then why do

English speakers say, ‘o’clock’ every time you tell the time?’

Hmm. Excellent

point.

Two points for

Filippo. And at least two extra weeks of freebie minutini.