This is a chapter from Jane

Fortune’s book

Invisible Women:

Forgotten Artists of Florence

Suspicious that artist

Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) had been poisoned by an envious maid, her father

forced authorities to exhume her corpse from a vault in the Bolognese church of San Domenico. Thus, the body of the

27-year-old artist, whose oeuvre equalled more than six times her age, was

examined by the court. The family’s maid, Lucia Tolomelli, was accused, exiled,

but later acquitted when medical experts discovered the painter had most likely

died of gastric ulcers. Art historians today-who marvel at the 170 works Sirani

produced during her short but vigorously intense lifetime-guess that her

fragile health was a result of exhaustion and overwork.

History remembers Sirani’s

father and first teacher, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was the principal

assistant to high-baroque painter Guido Reni, as a gout-ridden, money-hungry

Bolognese painter who spurred his daughter to take on an exorbitant number of

commissions-whose proceeds he himself collected. Elisabetta Sirani learned to

paint with elegance and refined classicism during her training with Reni, whose

style recalled that of Raphael. In 1655, when her father could no longer hold a

paintbrush because of arthritis, she took over his workshop; at 16 she became

the sole provider for the Sirani family. Her prolific career can also be

credited to her own innate speed in producing highly popular portraits and

widely praised allegorical and religious works. Though Counter-Reformation

Bologna was famous for producing astoundingly successful women artists,

Sirani’s clients were initially suspicious about the authenticity of her works.

Certainly a lovely woman painter who produced deeply complex iconographical

works at lightning speed had a team of hidden, probably male, collaborators.

To squelch these rumors and

testify to her skills, Sirani invited dignitaries from all over the world to

attend her public painting sessions, where wealthy commissioners and

wonder-eyed common folk gathered to witness the bold brushstrokes that became

many of her masterpieces, particularly those depicting daring female subjects.

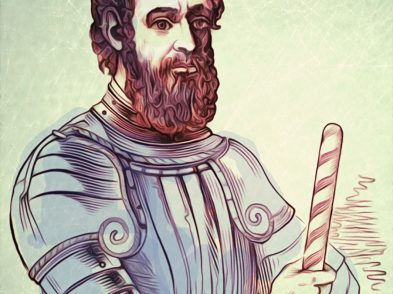

One such witness was Grand Duke

Cosimo III de’ Medici, whom Sirani welcomed to her studio in 1664. The duke

marvelled at her rendition of his uncle Leopoldo’s portrait and decided, on a

whim, to order a Madonna painting to take home for himself. Sirani produced the

commission on the spot, in hopes the work would dry before he was ready to

leave at the end of his afternoon visit.

A member of the Accademia di San

Luca in Rome,

Siriani inspired poets and orators who wrote of her praises. In Sirani’s

eulogy, Giovanni Piccardini, a lawyer from the University

of Bologna, honored her as ‘the glory

of the female sex, the gem of Italy,

the sun of Europe.’ Shortly after her death he

wrote Il Pennello Lagrimato, which captured the love her fellow citizens

professed for her. A biography celebrating her brief life was also published by

her mentor, Carlo Malvasia (with Crespi and Zanotti) four years later.

Well versed in both classical

and biblical literature, she was widely praised by the Catholic Church for her

Virgin and Child paintings and, at the same time, she eagerly portrayed

classical themes, which she intimately interpreted in a personal manner. An

independent professional painter by the time she was 17, she kept a catalogue

of her works. In addition to her 170 oil paintings, she produced 14 etchings

and a number of drawings, 31 of which are currently in Florence’s Gabinetto di disegni e stampe.

Executed in charcoal, pen and ink, or red or black pencil, these monochrome

sketches include five illustrations of the Virgin and Child, as well as several

figure drawings and other works depicting cherubs, saints and angels. Love

holding a heart in his hand and Saint Mary Magdalene taking off her worldly

ornaments are especially noteworthy. In 1994, the U.S. Postal Service selected

Sirani’s Virgin and Child, which is in the National Museum of Women in the Arts

in Washington, D.C., to print on 1.1 billion Christmas

stamps.

In her 1859 book Women

Artists of All Ages and Countries, Elizabeth F. Ellet writes ‘Sirani has

been pronounced a complete artist; unrivaled by any of her sex in fertility of

invention, in the power of combining parts in a noble whole, in knowledge of

drawing and foreshortening, and in the minute details that contribute to the

perfection of a painting. Had she lived longer she would have equalled any

artist of her time.’