As well as looking west in commemoration of Amerigo Vespucci’s donation of his name to America, ambitious thematic exhibitions in Florence this summer are also looking east. At the Pitti Palace, exhibitions spanning 500 years of Japanese art trace points of cultural contact with Italy from the time of the Medici to the present day.

Among Europe’s early contacts with Japan was the arrival in Livorno in 1585 of the first Japanese ambassadors to visit Italy. Accompanied by Jesuits, these emissaries travelled on to Florence, en route to Rome and the pope. Guests of the grand duke, they stayed at the Pitti Palace, now the location for three exhibitions that look at aspects of the exchange between two countries during 400 years.

For most of that time, Japan kept itself largely isolated from foreign cultural and political influences. But its leaders were eager for contact with foreigners, welcoming the Jesuits, for instance, when the religious order first entered Japan around 1549. What they did not welcome, however, was the European tendency to take over their hosts’ resources, and before too long they sensed that was a possibility. Not surprisingly, relations began to cool.

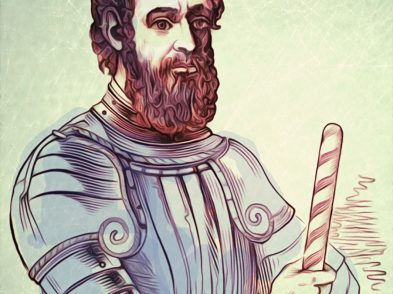

That caution encompasses the 300 years surveyed in Of Line and Colour, the exhibit in the Museo degli Argenti. The era was dominated in Japan by shoguns, the hereditary military dictators who held sway until the mid nineteenth century. The emperors displayed immense symbolic authority but possessed little actual power. Yet the combination of these forces produced not only a society in the grip of the military but also a highly developed artistic sensitivity both for the battlefield and the court.

Armour of exquisite elegance and beautifully worked lethal katana (swords) and tantō (daggers) have come to symbolise the period in popular imagination. Outstanding examples are on display here as are examples of more pacific production, such as the lacquer-work and ceramics that were also seeping into European consciousness by the eighteenth century.

There is no doubt that east and west remained very curious about each other. It was not until shogun power waned that Japan relented and extended trade links beyond a few foreign partners such as the Dutch and Chinese.

Then, in the half-century between the Convention of Kanagawa, brokered by US navy Commodore Perry in 1854, and the opening of Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly at La Scala in Milan in 1904, Europe and America became gripped in a frenzy to collect, imitate and learn from Japanese art.

The ukiyo-e woodblock print, or ‘floating world’ of perceived enchantment, and the original manga, figurative drawings, profoundly affected styles in painting, printmaking, furniture, ceramics, textiles and in graphic and jewellery design. The style became known as japonisme and its influence was as great in Italy as elsewhere. Examples reached the country at first mostly from Paris, where the Universal Exhibition of 1867 ignited the phenomenon explored by the show at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna.

In its widest applications, especially within the decorative arts, japonisme took hold in the manner of any craze, feeding eventually into the exotic line and curve patterns characteristic of Art Nouveau or Liberty styles.

On some visual artists, however, the impact of woodcuts by Hokusai, Utamaro and other artists was transforming. These spatially flat, asymmetrical compositions of landscape, ritual and everyday life in vibrant, unmodulated colours suggested new ways to imply space on the flat surface of a picture.

The effect appeared radical among those receptive to new ideas. In the 1860s Florence was both a capital city for a new Italy and a centre for advanced ideas in painting. Most significant were the Macchiaioli, artists developing a modern realism and seeking routes away from academic convention and outdated traditions. They were already lightening their canvases with effects observed in nature, and adapting to the lessons of photography and other discoveries.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the formal novelties in Japanese prints exerted strong influence. Such collectors as Luigi Passerini and Frederick Stibbert shared their finds with painter friends. Another channel was provided by Italian painters already settled in Paris. Artists visiting expatriates, such as Boldini and Giuseppe De Nittis, brought back news and one of these, Vito D’Ancona, created the highpoint of this show.

The figure in his Woman at the Races is seen from behind, walking away from the viewer and sheltering herself from sunlight under a broad parasol. Painted in 1873 in oil on a small wood panel, the echo from Japan in its bold pattern and bright colour is unmistakable. At the same time, she is a woman of her time, unaware that in this daring representation, East and West come artistically together.