In the late 1960s, the modern blockbuster art exhibition arrived and changed the museum landscape. Pioneered by such major institutions as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, these ambitious shows combined the art-world equivalents of Cinemascope, Technicolor, surround sound with a touch of Barnum and Bailey promotion. But shows on this scale do not tell the whole story. As the current exhibition at the Uffizi demonstrates, there is room for learned displays with a lower profile that reward the mind as well as the eye.

Temporary exhibitions have been a staple of museum programmes for many decades.

Originally conceived as small, well-researched displays of objects, including exhibits borrowed from private collections that visitors would otherwise have little chance of seeing, they encouraged careful looking and, sometimes, a specialist’s level of interest.

Nowadays, the blockbuster overshadows its competitors. This big beast brought a fascinated public the treasures of Tutankhamun, the petrified relics of Pompeii, innumerable Impressionists and the most glittering of old and new international art.

Even entire, priceless collections travel the globe to be greeted by long queues and excited marketing. They generate sponsorship deals and merchandising revenue that keep venues afloat, buildings up to date and curators in work.

These shows are good. Many have brought people into museums for the first time and made gallery-going an enriching habit. They both promote study and have woken up many galleries to the benefits of being truly public places, for families as well as tourists and art professionals.

There is, however, inevitably a downside. Conservators talk about masterpieces suffering travel fatigue; critics complain that the same subjects appear time and again because they attract paying crowds; and specialists fear creeping superficiality as hype triumphs over substance.

Above all, these mammoth projects are habit-forming. But they seldom offer the full story. Yet, in Florence, a valuable balance is being struck. So, let’s hear it for the Uffizi.

In spite of its incontrovertible global importance, the Uffizi is not a big museum. Compared with the Louvre, the Metropolitan and London’s National Gallery (where admission is free), its visitor figures are modest, coming just within the top 20. And, unlike its counterparts, it eschews blockbusters. Instead, the Uffizi has consistently produced mid-sized masterpieces of its own.

Each year, two or three exquisitely documented and sympathetically installed exhibitions occupy special rooms now located in the Nuovi Uffizi. Rather than being designed to fill gaps in income (a task, anyway, already well in hand), these shows fill gaps in knowledge.

It does not follow that they have limited appeal. Without doubt, the subjects may be obscure even to experts, eclectic and focused on brief moments in art history. Yet, although the exhibits are not widely known and the approach unfamiliar, the results in recent years have been visually remarkable as well as intellectually compelling. Primarily demonstrations of scholarship and curatorial diligence, they involve the visitor in discovering new stories in the history of old art.

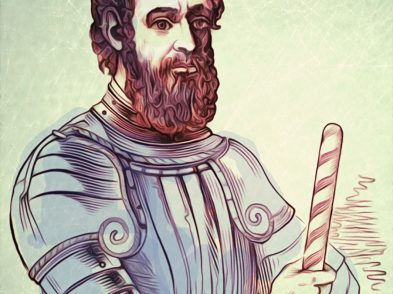

Take, for example, the current show, titled Norma e Capriccio (From Rule to Fancy), which brings together painting and sculpture from collections here and abroad to illustrate the contacts between Italian and Spanish artists in the early sixteenth century.

Why is that interesting? At that time, Spain was emerging as Europe’s superpower. But it was culturally conservative, while events in Florence were at the cutting edge. The Spanish artists who worked here, in Rome and in Naples were instrumental in taking home Renaissance styles in the arts and architecture. By 1640, Seville and Madrid were art centres rivalling Rome, and Velázquez’s career was reaching its peak.

So when Alonso Berruguete and Pedro Machuca were in Italy a century earlier, they laid important foundations. Machuca, for instance, helped channel Raphael’s innovations south to Naples, then a Spanish dependency, before returning to Spain.

They were also significant painters within Italy itself. Both followed Michelangelo, whom they probably knew, either as a friend or as a teacher, and both participated in the spread of new ideas.

These ideas principally concerned the maniera moderna. The style has become known as Mannerism and, after the realism, harmony and scale of earlier Renaissance styles, it can strike us today as artificial. Stretched proportions and eccentric poses characterise the saints and potentates of the best painters’ work, often executed in high-toned colours.

In a sense, its adherents did embrace ‘artificiality.’ They pursued a way of working that was sophisticated and poetic. They engaged the intellect with propositions about ideal form that went beyond the representation of reality.

Mannerism was provocative, but not intentionally, and in the first decades of the sixteenth century, it attracted the leading younger Florentine artists, among them Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino.

It was in this setting that the Spanish visitors worked as part of an avant-garde. Unlike the works of their Florentine peers, however, their contributions are barely acknowledged outside academia, in spite of their long-term value for both Italy and Spain.

Indeed, this exhibition would be an academic exercise if the work itself did not achieve a high quality. Mannerism permitted a degree of fantasy, a departure from Renaissance conventions that is consistently surprising, not least with its graphic strangeness.

Long necks, agitated expressions and the tense, often unbalanced character of the compositions catch off-guard the modern viewer who may find the strikingly compressed spatial setting of the image hard to enter imaginatively.

But the effort is worth the sensation of being drawn into an alternative reality. The artists go beyond visual experience in search of spiritual essences.

The marble St. Matthew and the Angel (c.1515) by Bartolomé Ordóñez is outstanding for the lively pattern of folds across both figures’ tunics. The surface seems to underscore the animated exchange inspiring the writing of the saint’s gospel.

The success of this show is its confident focus on an episode with which, by and large, we are unfamiliar. Through its calm installation and judicious selection, it makes us want to know more.

As with previous similar displays, the organisers have amplified the Uffizi’s own extraordinary holdings rather than distract from them. The permanent galleries lead into and away from this exhibition, taking the journey onwards along better-known routes.

Norma e Capricco: Spanish Artists in Italy in the Early Mannerist Period

Until May 26, 2013

Uffizi Gallery, Florence