In 2019, American classical musicians Zeneba Bowers and Matt Walker bought a 50 square metre apartment for 26,000 euro in Soriano nel Cimino, an hour north of Rome. This would become their new (and only) home six months later, when they quit their 20-year symphony jobs, obtained work visas, sold their house in Nashville TN, and moved to Italy (with four cats!) to live and work here as musicians, just three months before the pandemic lockdowns.

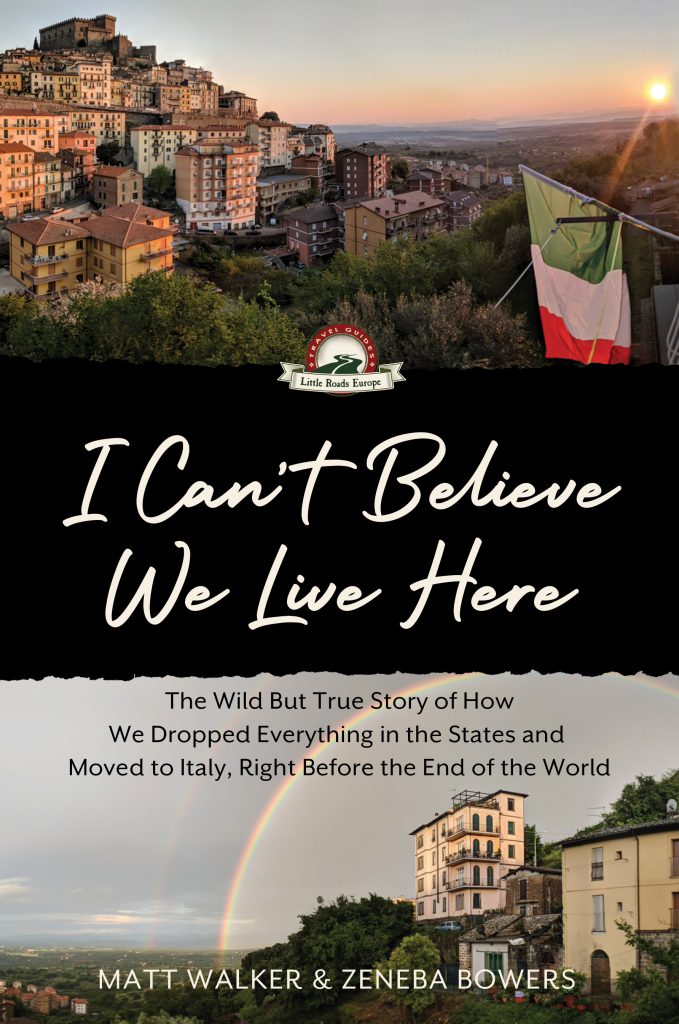

While in lockdown, with public events prohibited, they performed concerts from their little terrazza every evening for 62 nights in a row: first just for their neighbors, then into the PA in the town’s piazza, and then broadcast live on Facebook. This Buonasera Soriano concert series was featured on CBS Sunday Morning in May 2020, in a story about people playing from their balconies in Italy in the lockdown period. They wrote about the whole crazy experience in a recently published memoir: I Can’t Believe We Live Here: The Wild But True Story of How We Dropped Everything in the States and Moved to Italy, Right Before the End of the World.

In this excerpt, Matt and Zen meet with an immigration attorney in Florence (Michele Capecchi, himself a frequent The Florentine contributor) to discuss the possibility of moving to Italy. The answer was quite different than what they had expected.

Zen had an idea, which she conveniently shared with me in the middle of the night.

“I think we should talk to an immigration lawyer,” she said, her voice jolting me awake in the dark at 3 am.

The idea (she explained, once my heart rate had returned to something like normal) was just to learn about what could happen—what we would need to do to work in Italy, or perhaps to retire early there. At the very least, we could have somebody authoritative tell us we had no chance, so we could quit fooling ourselves.

As a married couple with jobs in the same symphony orchestra, we considered ourselves privileged. Such a job setup is a rarity in our business. Nevertheless, in recent years we had both been feeling that we were ready for something different. And we both wanted to exit our careers at a stage when people would still ask “Why are you leaving?” not “When are you leaving?”

Of course this was easier said than done. Most classical musicians, especially orchestra musicians, are not wealthy people. It’s a modest living. In this business, retirement tends to come late, if ever.

We had already done countless hours of reading on our own about various options for living full-time in Italy, and it was discouraging. Work visas were available for brain surgeons and rocket scientists, not for musicians or people with a side-hustle creating itineraries for tourists. A retirement visa seemed more likely, but not anytime soon. If we lived really frugally, we could maybe make that happen in five or 10 years. If we wanted to move sooner, we thought, we’d need some help.

After weeks of dogged and exhaustive research, Zeneba came up with a name of an avvocato in Florence whose practice specialized in navigating the choppy waters of immigration into Italy. He appeared to be an out-of-the-box thinker, somebody who might be creative about how to make our idea happen.

We set up an appointment to consult with this lawyer, with lower than low expectations. We assumed he’d say “Forget it,” followed by “Let’s call that an hour… that’ll be 240 euro, per favore.”

At this point we already had a trip to Italy scheduled for April. The symphony set and controlled our work schedules far in advance, and we built our own travel planning around that. We had worked out a short period of time off, which meant we’d have a tougher schedule for the rest of the season. Not only was the orchestra work incessant, but we had also started accepting every other possible freelance recording session and side gig to balance out our sudden spending for the new apartment. Other than this trip in April, we were working seven days a week from March until the end of summer.

Our plan had been to use that trip to do some travel research and gather information for a second edition of our small-town guidebook to Tuscany. But given the crazy thing we had done in February, we decided we’d better spend some time in Soriano to finish the house purchase and get the place organized. So why not also squeeze in a visit to Firenze to meet with this immigration lawyer? It seemed audacious, but again it just felt like the right step to take in this series of events.

April arrived, and we stepped off the plane in Rome with a different mood and different goals compared to our previous trips to Italy. Yes, we would still be ingesting copious amounts of wine and cheese and staying in 500-year-old buildings, but this time we were taking baby steps toward the notion of actually living here. Buying the apartment had been the first step; this avvocato meeting was the next.

After a few days of visiting some little towns in Tuscany, we showed up in the “big city” of Firenze. Over the years, we have built an entire travel philosophy (and business) around not visiting such large and heavily touristed places. Though it’s generally regarded as “small”—much smaller than Nashville, and dwarfed by the likes of Rome or New York—we find the sheer size and grandeur of Firenze incredible but overwhelming.

Every step we took that day is now etched in our minds. Though just a block away from the Duomo, our guy’s law offices were in a cluster of professional businesses—banks, real estate brokers, insurance companies, accounting firms, and government offices—not a spot frequented by tourists. We walked up to the big front door and rang the bell, and the receptionist buzzed us in. It was a 250-year-old building—relatively new for Firenze. We climbed the three stories to his floor, and stepped into his office. It was an old, classic lawyerly interior, with fancy antique furniture and people in impossibly cool business suits with shoes that were shiny, not scuffed-up slip-on Skechers like mine.

We felt out of place in our usual dumpy clothing.

“Well, just ask yourself if any of these guys go to work regularly in a white tie and tailcoat?” Zen tried to reassure me.

“I’m sure they’d be impressed by our black concert clothes with the white-cat-hair accents,” I shot back with a grin…

But this wasn’t really helping to set either of us at ease in this unfamiliar environment.

The avvocato was perfectly amiable, listening patiently as we explained that we’d like to move to Italy to work, or at least to retire here someday: Buying the little house, planning to write our next guidebook, and so on. We thought our travel books and our business of making itineraries might be of interest to the Italian government. We’d love to be able to live here and do that sort of work, which theoretically would be good for Italian businesses and individuals.

Through all this, the avvocato smiled and nodded.

Then he leaned back. His fancy leather chair made that fancy leather chair sound.

“Okay,” he said. “Nobody will care about the travel stuff. The thing you two have that is compelling is your background as musicians.” He flipped through the papers on his desk—the materials we had sent him ahead of time so he’d know something about us. “Twenty years in that orchestra, this long list of impressive people you’ve performed with, the CDs you produced, Grammy nominations, directors of your chamber ensemble, and so on.”

The upshot was, we could request work visas to be concert performers and organizers of cultural events. We explained that we had been thinking about doing less music, not more. In fact, we wanted to gradually get out of the music business, to start doing more of our travel consulting work.

“You can still keep doing that, too,” he explained. “But this is how we get you in here—as experts in music.”

Zen and I were looking at each other, thinking about this idea, when he added, “And you should do it now. Not in a few years, not next year. Now.”

The word just hung there in the air. So did our jaws.

He explained: The Italian government had recently released their work visa quotas for that year, and among the categories they were accepting were a few of these cultural/arts visas. The avvocato’s help with the work visa application would not be cheap—a package price of some 4,000 euros. On the other hand, he had a perfect record: Every application he had ever filed had received approval from the government.

We took a deep breath and told him we’d discuss it. We calmly thanked him, casually handed over his fee for the hour, and coolly walked out of the offices, down the stairs and out to the street. Once we had gone a block or so, that facade of calm, cool casualness evaporated and we proceeded to lose our shit.

It sounded too good to be true. We knew it was a long-shot. We knew it would take an as-yet-inconceivable amount of logistical work and an even greater amount of luck.

We were overcome by sensory overload as we walked out of the lawyer’s office onto the streets of Firenze. The famous Duomo a block away; gaggles of tourists; sharp-dressed Italian men and women darting between businesses; the aroma of espresso and colognes. We were agitated—a combination of excitement and trepidation—and we needed a quiet place to sit and talk about the options that had just been revealed to us. But this major metropolitan street in a highly touristy area wasn’t it.

Despite the chaos, both on the street and in our minds, we stopped on the sidewalk and looked at each other.

“What the hell,” Zen said. “Let’s do it.”

“Okay,” I answered. “Let’s give it a shot, at least.”

“LET’S DO IT!” she repeated at the top of her voice, clapping her hands with joy like a little kid.

That was the moment we decided to leave the US.

Seven months later, we started a new life in Italy.

I Can’t Believe We Live Here: The Wild But True Story of How We Dropped Everything in the States and Moved to Italy, Right Before the End of the World is available on Amazon.it.