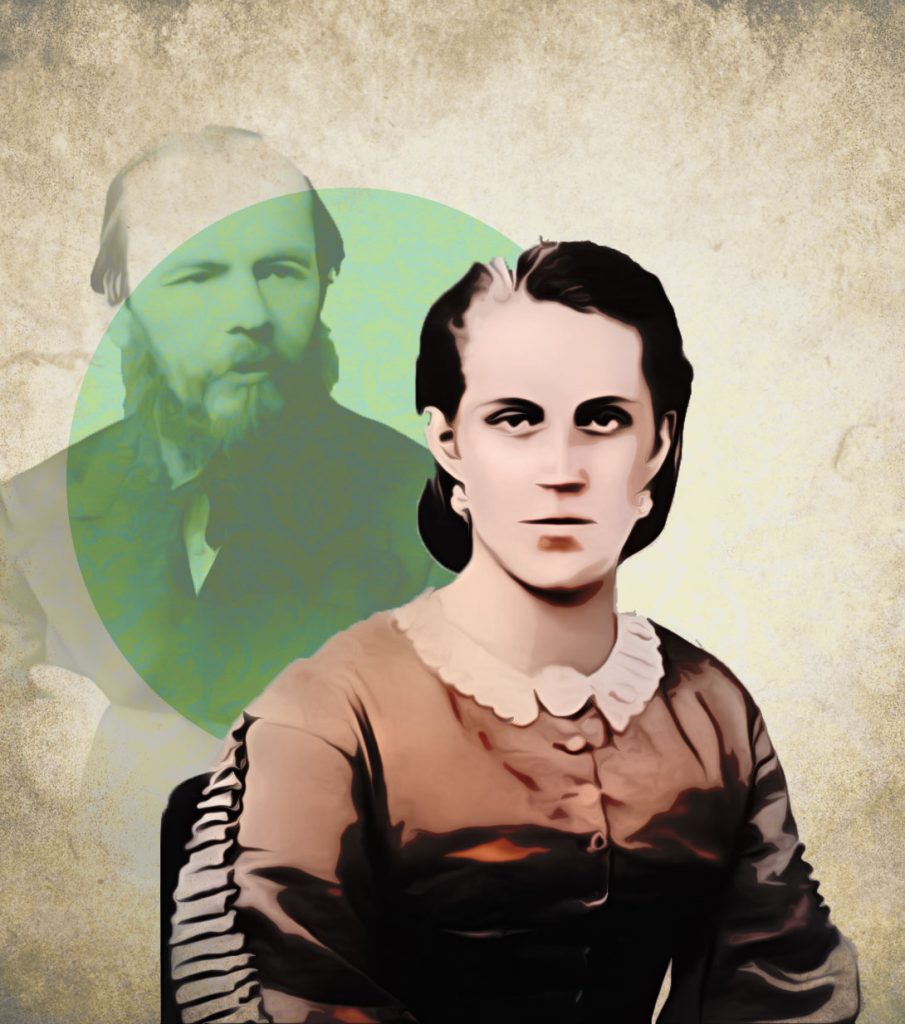

A plaque on the wall above via Guicciardini 8, a building facing the Pitti Palace, recites that it was there that the Russian writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-81) finished his book The Idiot between 1868 and 1869. The writer had already briefly visited Florence with his friend, the philosopher and literary critic, Nikolay Nikolayevich Strakhov in 1862, but this was the first visit for his young second wife, Anna Grigorievna Snitkina (1846-1918).

On the run from creditors, the couple arrived in the city, then the bustling capital of Italy, in the autumn of 1867 and initially lodged at the Pensione Suisse on the corner of via Tornabuoni and via della Vigna Nuova. The Guicciardini apartment was next until they moved to a house that a friend had loaned them overlooking the Mercato Nuovo after Anna’s mother arrived to help her pregnant daughter. In a letter written in May 1869, Dostoevsky tells his friend, the poet Apollon Maykov, how he feels: “The heat in Florence is getting awful; it is a suffocating city, burning hot. The nerves of all of us are on edge – which is particularly bad for my wife. We are crowded at the present moment… in the smallest, tiniest little room, facing the market. I am sick of this Florence, and now because of the heat and the overcrowding I can’t even sit down to work. On the whole, terrible nostalgia, the worse for being in Europe; everything here makes me feel like a beast.” Their only relief from the heat was to take walks in the shaded Boboli Gardens or the Cascine, while Dostoevsky would often escape to the Vieusseux Library to read Russian newspapers after lunch.

A morose and irascible 45-year-old widower, Dostoevsky met Anna in Saint Petersburg in October 1866 when he employed her as a stenographer, so that he could dictate his novel The Gambler to meet the strict deadline an unscrupulous publisher had imposed on him. Although she was 25 years younger than him, he wasted no time and married her three and a half months later, much to his family’s displeasure. Their early years together were plagued by his gambling addiction, including times when they lived in Florence and he would scurry off to Germany to play the roulette tables and inevitably return empty-handed. He was also subject to fits of jealousy and mood swings, worsened by a constant lack of funds and the premature deaths of two of their four children. Nonetheless, they were in love and Anna had quickly become indispensable to him. He dedicated The Brothers Karamazov to her when it was published in 1880, while she devoted her entire life to nurturing his genius and shielding him.

When they returned to Russia from their four- year European sojourn in 1871, Dostoevsky kept his promise: he stopped gambling and handed the family’s financial management over to Anna. She quickly discovered he had been paying out sums to rogues who falsely claimed he owed them money. Anna also sought information about publishing wherever she could and started the first Russian publishing house owned by a woman. She also created a profitable publishing model by marketing several editions of her husband’s complete collected works. This way, she soon had them solvent and debt-free.

Apart from being an astute business woman, Anna became one of the first female philatelists in Russia, refuting her husband’s theory that women were incapable of constancy. In her Reminisces, she recounts she never spent a penny on any of the stamps. Instead, she found them or they were given to her.

After Dostoevsky died suddenly from a haemorrhage in January 1881, his Orthodox funeral was held at the Church of the Holy Spirit at the St. Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg. Despite the freezing temperatures and biting wind, it was estimated that 100 deputations participated in the procession and 100,000 people lined the route to the monastery, with another 20,000 to 30,000 following the coffin. Although

Anna was only 35 at the time, she would never remarry. Instead, she focused on preserving Dostoevsky’s legacy by collecting his manuscripts, letters, documents, photographs and other memorabilia. In 1899, she donated 1,000 of these items to the State Historical Museum to set up a room in his honour.

In 1906, she published The Bibliographic Handbook of the Works and Artistic Writings of F. M. Dostoevsky in Relation to his Life and Activities. She also wrote Fyodor Dostoevsky: Anna Dostoyevskaya’s Diary in 1867, which was published after her death in 1923, and Dostoevsky, Reminiscences in 1925. She opened the family’s summer dacha to the public and established a parish school in her husband’s name for children from poor peasant families.

Anna died, ill and starving, in Yalta in the war that ravaged Crimea in 1918, and was buried there until her remains were transferred to the St. Alexander Nevsky Monastery in 1968 to rest alongside her husband.