Early women artists are often depicted as rebellious souls who “wreak havoc” by overturning social expectations. In Florence, Artemisia Gentileschi shocked her fellows at Casa Buonarroti by painting her tribute to Michelangelo on the gallery ceiling while five months pregnant. In France, not too long ago, Rosa Bonheur was arrested for painting in public—in trousers. Stories of women artists and their “indiscretions” undoubtedly give us a thrill, but in this article I’d like to look at the “small” but fascinating transgressions that characterize their art—not their lives. A large part of reclaiming the history of women painters lies in making it a point to see their works. When you find yourself contemplating art by women, here are a handful of details worth noticing. Before you “break the mold”, first you have got to put a crack in it!

Giovanna Garzoni (1600-70)

A “happy” medium

We can credit the Medici for supporting the development of two artistic genres: portraiture and still life. The dynasty was not of noble blood and they needed richly adorned images of themselves as a marketing tool to woo Europe’s most powerful. But beyond their stately ambitions, several grand dukes commissioned still-life works as a personal passion, such as Ferdinand II de’ Medici and his wife Vittoria della Rovere. Giovanna Garzoni’s 21 watercolors in the Palatine Gallery’s Sala delle Vetrine pay tribute to their love for scientific realism. Nonetheless, they are first and foremost merit of the painter who was their protégé during her artistic sojourn in Florence from 1646 to 1651. Look past her amazing detail. Look past her crawling insects and her overflowing fruit piled high in ceramic bowls. Notice how Garzoni’s lovely compositions are painted against light backgrounds. That is where her innovation lies. Whilst most flower painters of her age constructed rather gloomy canvases, Garzoni had the courage “to turn on the light”.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842)

A toothy grin?

Many people “met” Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun at the Met last year during the exhibition “Woman Artist in Revolutionary France”. But we have had her in Florence all along, as part of the Uffizi’s collection. In 1787, Vigée Le Brun painted a self-rendition showing her teeth, a choice for which she was widely criticized. She risked “being vulgar” again with the Uffizi self-portrait three years later and was boastful of the end result: “My painting in Florence enjoys great success,” she wrote in a letter. “All artists have come, come again; the princesses of all countries, the men even. They call me ‘Madame Van Dyck’ and ‘Madame Rubens’.” Vigée Le Brun’s “audacity” and subsequent success reminds me of that time-tested refrain: you are never fully dressed without a smile.

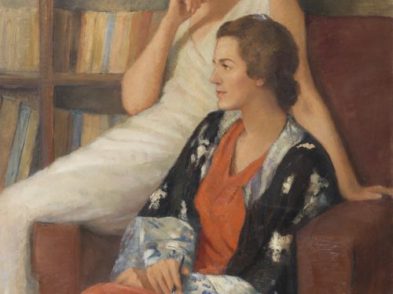

Louisa Grace Bartolini (1818-65)

But she’s…

The obsession with youth is not a 20th-century phenomenon. Long before the age of photography women sought to be “immortalized” in the best, most youthful light. This ambition is understandable among Tuscan noblewomen as flattering portraits were often used to secure advantageous marriage proposals. In self-portraiture, idealization is the most common trend, even for women painters whose primary purpose was to establish themselves as masters of their craft. (Nearly all female artists in the Uffizi’s collection, for example, portray themselves with paintbrush or palate in hand.) Louisa Grace Bartolini was an English-born adoptive Tuscan painter who lived in Pistoia in the early and mid-19th century. One hundred and twenty-five of her drawings and paintings can be seen (upon prior written permission) in Florence’s Marucelliana Library. And yes, in one particularly interesting self-portrait, she is actually “old”!