Nearly 400 pairs of eyes follow the visitor down the elevated passageway that stretches from Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio to Palazzo Pitti. In 1565, Cosimo I de’ Medici commissioned Giorgio Vasari to design and build (in just five months!) the one-kilometer structure that became known as the Vasari Corridor in time to impress the wedding guests who gathered to celebrate the nuptials of his son, Francesco de’ Medici, to Johanna of Austria. As the Arno River flows underneath, the paintings hanging on the walls chronicle the ebb and flow of the city’s artistic currents and the personalities who moved them.

Whether a way to outsmart bloodthirsty enemies or a singular symbol of Medici authority, Vasari’s unique construction linking the city’s administrative headquarters to the Medici’s imposing residence has become a venue for one of the most ancient forms of artistic expression: self-representation. Today, the private walkway that once allowed Florentine nobility to avoid rubbing elbows with the common folk permits visitors to meditate on the power of art history’s greatest protagonists.

The Vasari Corridor, which can be visited only by appointment, has a collection that includes 1,630 self portraits, yet only 400 are exhibited. The collection was started in the seventeenth century by Cardinal Leopoldo, and only 10 of the displayed works were created after 1900. Self portraiture, one of the most easily accessible themes for female painters, was a well-respected genre in Florence and many women have been honored by the coveted invitation to paint their own image for the Medici collection. However, only 6.5 percent of the works on display are by women, a statistic that translates into 27 exhibited works by 21 women.

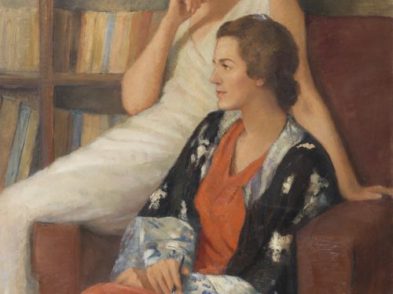

A rare combination of image and substance, the self portraits merge honest observation with beguiling personal representation, blurring the distinction between maker and muse. Thus, the varying expressions of the women in the collection inspire an entertaining labor: looking at countenances for hints of hidden temperaments. Those visitors intent on scrutinizing the faces in search of clues to the artist’s character will note Lavinia Fontana’s air of solemn grandeur and Sofonisba Angiussola’s demurely maintained simplicity. And who can help but admire the sophisticated image of elite American portraitist Cecilia Beaux or wonder at young Rosa Bonheur’s surprisingly traditional rendition of herself. Angelica Kauffman’s predictable but lovely self-idealism makes her just as much a princess as any of her corridor companions who were born with bluer blood. Less angelic but equally appealing, Dona Mariana Waldstein, the Spanish Marquesa of Santa Cruz, sits before the cup and saucer she intends to paint. And the last Electress of Saxony, the older, wiser Maria Antonia Walpurgis, dons a dress with wide blue ruffles and holds her fan closed, assuming a tight-mouthed, dignified pose. With the same distinguished air and elegant dress, Bolognese painter Lucia Casalini Torello holds her paintbrushes instead of a fan. ?lisabeth Vig?e-Le Brun cannot hide her high-spirited gaiety, and the slim-faced Neapolitan Princess of Belmonte, Chiara Spinelli, avoids the viewer’s questioning gaze, not bothering to disguise her royal melancholy.

ARCANGELA PALADINI

The hauntingly beautiful Arcangela Paladini (1599-1622) gazes into the visitor’s eyes with an assuredness uncommon for her youth. In her 2004 work From Saint to Muse: Saint Cecilia in Florence, art historian Barbara Russano Hanning suggests that Paladini served as a model for Saint Cecilia, the patron of musicians, in one of Artemisia Gentileschi’s paintings; if true, it would have been a fitting choice: Paladini was widely acclaimed for her angelic singing voice. The Pisa-born daughter of Florentine portraitist Filippo Paladini (1544-1616), a student of Alessandro Allori (1535-1607), Paladini was an accomplished painter, singer and poet by the time she turned 15.

Impressed by Paladini’s multiple talents, Archduchess Maria Maddalena of Austria, wife of Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici, invited the artist to join their court. Maria Maddalena became the artist’s most faithful benefactor and it was upon her suggestion that Paladini wed Jan Broomans of Antwerp at age 17. In 1621, she was commissioned to create her self portrait for the Vasari Corridor. Paladini passed away six years after her marriage and the archduchess grieved her untimely death, burying the 23-year-old in the loggia of Florence’s second oldest parish, Santa Felicit?, whose fa?ade intersects with the Vasari Corridor (the Medici family, unseen by the congregation below, would attend mass undetected, gathering alongside its heavy gated window).

Restored in 1967, Paladini’s modest yet compelling self portrait was once one of the collection’s most celebrated works.

GIULIA LAMA

Venetian painter Giulia Lama (1681-1747), the first woman known to draw and study the male nude from a live model, was similar to Paladini in terms of her skills as a painter and poet, but unlike the young Pisan artist, Lama’s physical appearance hindered, rather than propelled, her professional success. Nonetheless, Lama’s poems are often compared to those by humanist poet Francesco Petrarch, and she possessed ample knowledge of mathematics and a passion for philosophical studies. Although very little documentation survives about her life and works, scholars have uncovered a treasure trove: 200 of her drawings featuring both male and female nudes. She is said to have been trained by her father, Agostino Lama, before studying alongside Giambattista Piazzetta (1682-1754), a rococo painter and her childhood friend. While Lama’s paintings are similar to Piazzetta’s in their sharp contrasts of light and shade, her technique is said to surpass his. The homeliness of her unadorned self portrait, painted when Lama was in her early 40s, seems to exaggerate her unattractiveness, perhaps to provoke her critics, who repeatedly sustained that no one so plain could possibly produce such engaging paintings.

Whether portraiture can be classified as a primal means of individual expression or perceived as a form of personal publicity, it is certainly one of art’s most explored genres, which arises as an artist comtemplates her most readily available source of inspiration: the self. To this point, Artist Frida Kahlo once remarked, ?I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.’

This is a chapter from Jane Fortune’s latest book, Invisible Women: Forgotten Artists of Florence.