What better place to pay attention to the nuances of language and its impact on how we see the world around us than the birthplace of Dante Alighieri, the father of modern Italian language? His epic poem The Divine Comedy was the first major work written in the Florentine vernacular. With this masterpiece, the Tuscan dialect was raised to the language of high culture, setting the standard of Italian still used today and becoming a source of pride to Florentines.

Empoli native Enrico Cecconi, coordinator of Italian language studies at University of Bath, UK, and my former Italian professor at Accademia Europea di Firenze, expressed this pride in Italian to me. “Speaking Italian is more than the pleasure of producing beautiful and musical sounds or using gestures and more than just a linguistic skill. It has the magical power to allow you to inhabit Italy’s history and culture that the language shapes. We Italians live in the piazzas between tradition and modernity, having conversations in front of historical cathedrals or during an aperitivo al fresco. Our culture flows, changes, and so does the language.”

Italian, like all languages do for their respective cultures, conveys an essence of what it means to be Italian that cannot be fully understood using other languages. Language is the gateway to understanding and embracing a culture.

In the 1930s, Benjamin Lee Whorf, an MIT-educated U.S. American linguist and chemical engineer, and his mentor Edward Sapir, a German linguist and anthropologist, popularized the general idea (known as the Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis) that the structure of language affects how people think and perceive the world. More recent scholars are discovering specific ways that language influences our thoughts and behaviors. For example, Ken Chen, professor of economics at Yale University, found that people who speak languages that require the use of the future tense (such as English) are less likely to save money and generally engage in riskier behaviors than people whose languages are largely devoid of tenses (such as Chinese) because they tend to dissociate the future with the present. Lera Boroditsky, a cognitive scientist and professor at University of California, San Diego, maintains that people who speak languages that have gender-specific nouns tend to describe inanimate objects with stereotypical gender traits.

Another way that Italian affects our perceptions of the world and understanding the soul of Italy is in its idiomatic expressions.

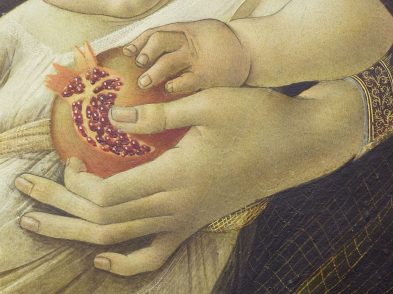

There are dozens of Italian turns of phrase connected to food and the Italian dinner table. A tavola non s’invecchia (“At the table, one does not grow old”), Mangiare per vivere e non vivere per mangiare (“Eat to live, don’t live to eat”) and Due dita di vino e una pedata al medico (“Two drops of wine and we can kick the doctor out the door”), in contrast to the English equivalent of “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” are not just folksy expressions; instead they reaffirm the centrality of food and wine as the marrow of Italian culture.

But you don’t have to vaunt a mastery of idiomatic expressions, nor be fluent, to reap (and sow) the benefits of speaking some Italian during your next trip to Florence. Simply trying to speak the local language and using Italian words and phrases in everyday life will make you feel more Italian. When I ask for normale, I’m not just asking for a cup of coffee; I’m participating in a normal ritual of daily Italian life. When I leave someone with buona giornata, I’m not making a polite salutation; I’m demonstrating my respect for Italian culture. When I say per favore, grazie mille or prego, I’m not just being courteous; I’m expressing my gratitude for welcoming me and my willingness to overcome my ethnocentrism.

In her book In Other Words, Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winner Jhumpa Lahiri explored her personal metamorphosis that resulted from learning to write in Italian. When asked during an interview with The New Yorker magazine why she has continued to write books in Italian rather than in English, her mother tongue, she explained simply, “I think, see, and feel differently in Italian.” What better reason can there be to learn and to speak Italian!