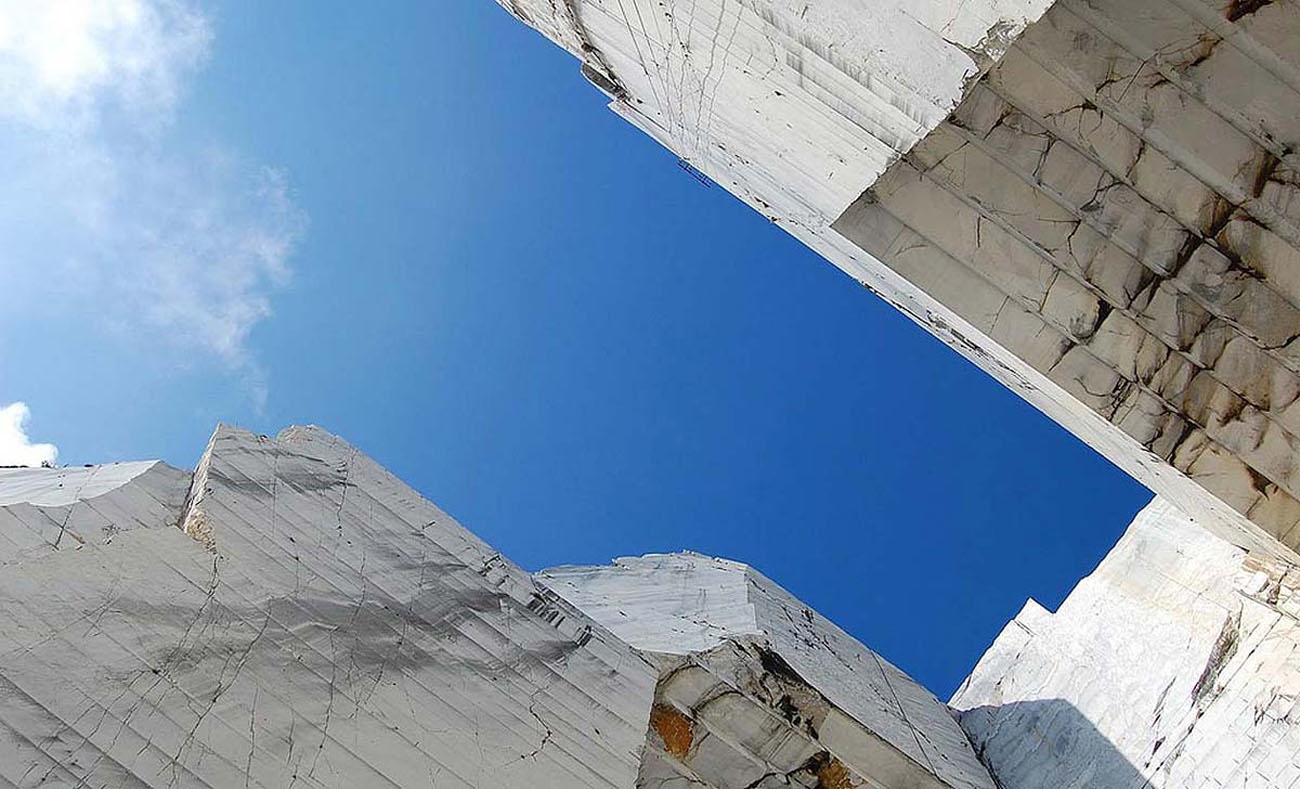

500 years have passed since Michelangelo forged his marble road, extending from Seravezza to the heel of the Trambiserra and Cappella quarries. One of the many roads crossing the Apuan Alps, it is imbued with a legacy that has shaped the character of all towns in Alta Versilia.

That character is as hard as the stone chiselled over generations, as tough as the bunions of the hands that extracted marble over the centuries. There’s a masculine appeal to it, particularly in Seravezza, a place with all the rugged frankness of a dirty-handed quarrier, as the writer Enrico Pea described it. You see the spirit of marble manifest in the daily life of Carrara, Pietrasanta, Seravezza, Arni, and you see it reflected on the porches of the households, the coffee tables, the altars of the parish churches, the images carved in the marginette.

But it’s the marble memory of Michelangelo that makes the strongest impact. As early as 1515, the Uomini della Comunità di Seravezza e della Cappella association of quarry workers made some strategic concessions to the Repubblica Fiorentina, aiming to increase and improve jobs. Just two years later, Pope Leo X sent Michelangelo on an excavation mission, aimed at finding the right marble for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence (which was never completed).

During his time in the area, Michelangelo laid out the design of a rosette for the Azzano Chapel, a Romanesque pieve that regally overlooks Versilia. Now known as the Eye of Michelangelo, this rosette “gazes” outward onto the many young, international artists who arrive here every summer to carve, study and breathe in the air of centuries-old chestnuts and millenary marble.

Each century after Michelangelo saw its own developments. Most notable for the 1600s was the takeoff of square marble tile production. In the 18th century, marble blocks were sent down the Michelangelo-blazed path by cableways and ropeways, then were loaded on ox-led carriages and brought to the seaside where they would be shipped. This modus operandi continued well into the early years of the 1900s, but by the 1960s, the Cappella quarries no longer had marble to offer.

This had little effect on the legions of artisans and artists who continue to carve out creative space here, keeping the “memory of marble” alive. A vibrant community of foreign-born artists charges on in the many schools and workshops of Pietrasanta, while Seravezza treasures the legacy of the greatest sculptor to ever give body and soul to stone. With two servants, a horse and pre-paid accomodation, in 1517 Michelangelo spent hard months in these hills, ceaselessly working with the quarrymen of Azzano, paving his way to Monte Altissimo, right to Tacca Bianca and to La Fitta.

Today, the road is no longer used for transporting marble, but at the Azzano Chapel, overlooking the Versilia coast and the Apuan outline in the distance, one can still hear the marble being chiselled against the silence of the valley. The sound no longer comes from the quarrymen of Azzano, but from the young artists hailing from around the world, who only here can find sufficient inspiration and stimulus to carve their own marble roads.