When Michelangelo died in Rome at the venerable age of 88, the first priority was to bring his body back to Florence for appropriate burial and commemoration. This eventually took place in an impressive tomb monument in the Church of Santa Croce, which was designed and partially carried out by Giorgio Vasari to honour the memory of the great artist Michelangelo and to state the importance of his family. Behind their monumental appearance, these masterpieces hide the stories of the people they celebrate and those who built them: curious events, accidents and anecdotes that show how history repeats itself and that human nature never changes.

The stolen body of a political dissident

Even though Michelangelo was Florentine and loved his town, he spent the last three decades of his life in Rome. This self-imposed exile started when Alessandro de’ Medici was made the first duke of Florence. Michelangelo considered him a tyrant, so from the 1530s, even after Alessandro’s death, he preferred living under the rule of the popes in Rome.

When Michelangelo died on February 18, 1564, he was initially laid to rest in the SS. Apostoli church in Rome. However, when Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici heard about this development, he declared that since he was not able to employ Michelangelo and honour him in Florence during his life, he would honour him in death with a state funeral and a proper tomb in Florence. Lionardo Buonarroti, Michelangelo’s nephew and heir, was assigned the task of ‘stealing’ the corpse. He had it sent secretly in a bale of hay, disguising it as a piece of merchandise. This way, no one in Rome, including the Pope, would be able to prevent the movement of Michelangelo’s body back to Florence.

Michelangelo like a saint

Chronicles often report that after saints die, their bodies remain in good condition and they smell good. This phenomenon could last for years after a saint’s death. People saw this as concrete proof of the unique, divine nature of a saint. When Michelangelo was brought back to Florence, it had been 20 days since his death. The still-sealed coffin was opened in front of a large group of witnesses, who were all surprised that the body had not decayed or decomposed, and that it had a good scent.

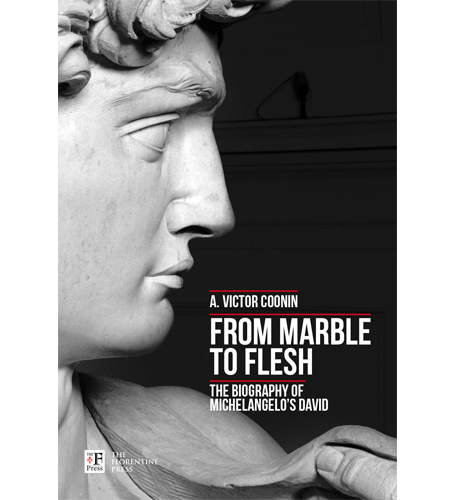

From Marble to Flesh. The Biography of Michelangelo’s David

Prof. Victor Coonin tells the story of Michelangelo’s David as if it were a biography, from the quarrying of its marble near Carrara to his adoption by contemporary artists. And in between, a litany of desires, contracts and conflicts, artistic and political decisions, and much more that makes this the most famous statue in the world.

A political statement

Cosimo I hired the artist Giorgio Vasari for this project because he trusted him to understand and implement his vision for Michelangelo’s monumental tomb. On the monument next to the artist’s bust, there are three intertwined laurel wreaths. These wreaths represent the union of the artistic domains of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, all of which were profoundly impacted by Michelangelo’s work. These laurels are also the logo of the Accademia dell’Arti e del Disegno, the academy founded by Cosimo I de’ Medici in 1563. The symbol was inspired by the three circles that Michelangelo had crafted to mark the marble he would use for the tomb of Pope Julius II. The epitaph on the base of Michelangelo’s purple marble tomb states the crucial role that Cosimo I played in preserving Michelangelo’s memory and artistic legacy, despite never having been able to benefit personally from Michelangelo’s art.

Very “old school”

The project includes traditional symbols and imagery relevant to Michelangelo. The artistic domains of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture are depicted as three muses mourning the loss of this great artist. Each holds the tools of the artistic trade she represents, and which are still used by painters and sculptors today. The figure of Sculpture is also very up to date, thanks to her pose resting one foot on top of a marble brick with chisels and a hammer. This is a pose demonstrating power and control over something, and it dates back to antiquity. For example, David could take this pose, putting his foot over the defeated Goliath’s head. Christ could put his foot over the tomb that he will leave to re-ascend to Heaven. More often in modern society, we see soccer players proudly taking this stance, with one foot over the soccer ball, holding it in place. Only the muse of Architecture appear obsolete. The compass, square set and rulers used in Michelangelo’s time have been replaced by computer software.

Costs more than a house!

Lionardo Buonarroti, who commissioned Vasari and his team, spent the massive sum of 770 scudi on Michelangelo’s monumental tomb. Originally, he had expected to pay 500-600 scudi for this project, but in the end, the bill was higher than anticipated – a bill that Buonarroti contested in court, but lost. The project ended up costing as much as seven farmhouses around the castle of Montalto and a group of houses in the city of Siena. Material expenses, including marble, were paid by Cosimo I. The work itself took a very long time as well. It became a nightmare project for its artists and builders, taking 14 years to complete, from 1564 to 1578, due to several delays. One of the major complications was the marble, because the material had been extracted from Carrara and Serravezza in 1566, and was stored in Pisa, where it was waiting to be shipped to Florence. In 1567, when this new marble was requested, the storage manager was unable to find it. Therefore, another extraction was required, and this extraction of marble finally arrived at the project site in Florence in 1568.

The history of this monument isn’t over yet. The monument to Michelangelo and the Buonarroti family altarpiece in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence will soon be restored. In order to obtain the financing, after the successful result of “Crazy for Pazzi” crowdfunding campaign, the Opera di Santa Croce opened a new international fundraising campaign “In the Name of Michelangelo”, with the goal of raising €100.000 by October 30, 2017.

Michelangelo’s tomb restored in Santa Croce

The restoration of Michelangelo’s tomb at Santa Croce was financed by over 100 donors from 12 countries, 80 per cent of them U.S. citizens.