Orgies on a dancefloor. That’s what I saw in the Super 8 footage I found in my father Fabrizio Fiumi’s archive when he passed away four years ago. Like with the rest of his archives, I have had to research every item to discover its meaning. What had looked like orgies was simply a theatrical performance by the Living Theatre, an avant-garde New York-based troupe that performed Paradise Now at my dad’s Space Electronic nightclub in Florence in 1969.

From New York to Florence

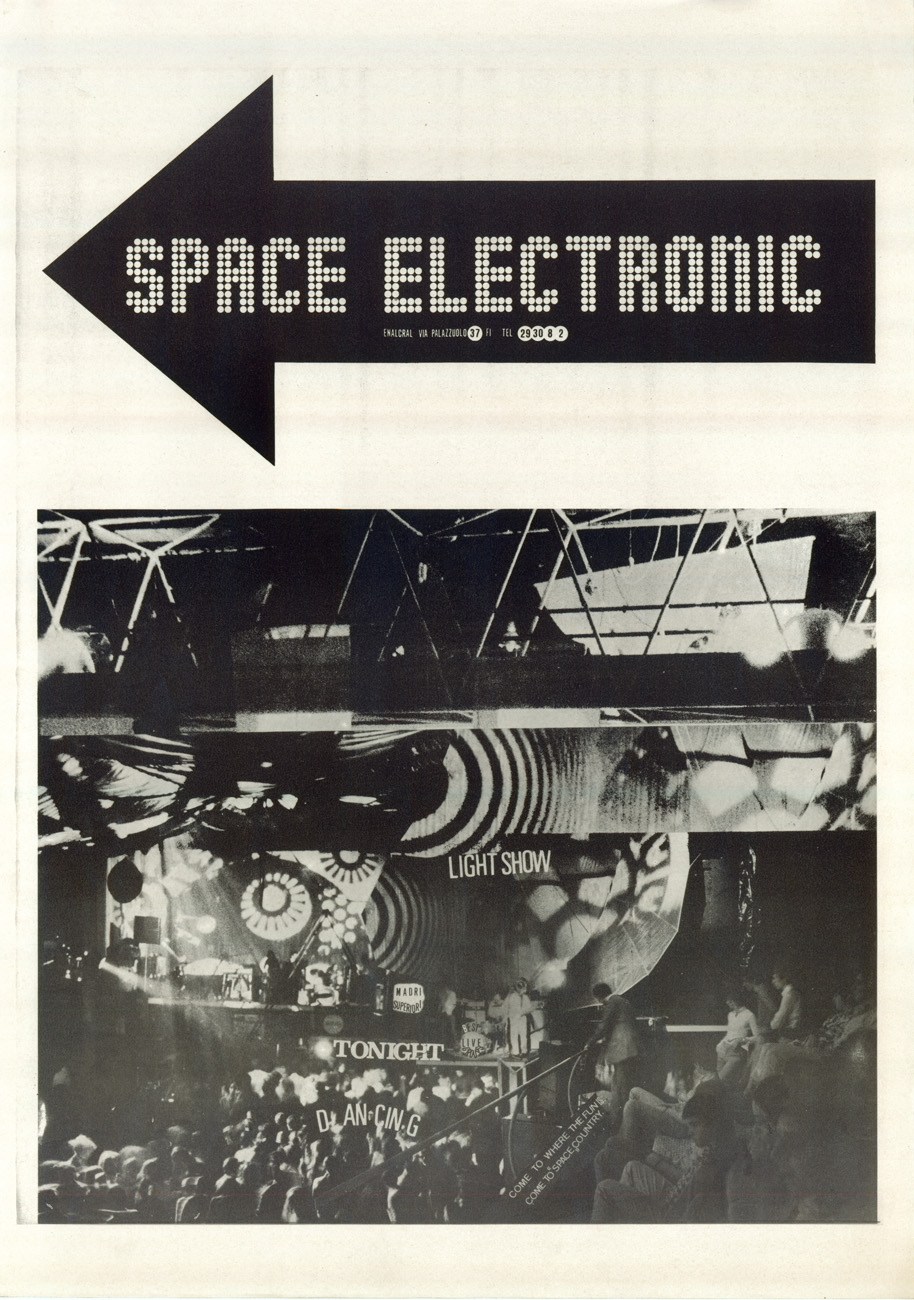

The Space Electronic was shocking because it was unexpected and provoked thought. A multimedia environment that started as my father’s thesis project, the Florentine space was inspired by his travels to the United States with Carlo Caldini and Mario Preti. New York’s Electric Circus was one source of ideas due to the East Village discotheque’s light shows, as too was the Buckminster Fuller pavilion at the Montreal Expo, an aesthetic reference for the parachute the trio bought in Cupertino, CA, which they hung above the dance floor.

New York’s Electric Circus was located just below Andy Warhol’s Loft and down the block on St. Marx Place in Greenwich Village from where Zappa was playing for six months at the Garrick Theater.

The architecture was particular: black-and-white tile bathrooms replicated endlessly by mirrors, a metal catwalk that supported the light shows, a continuously changing interior with dishwasher drums as seats and interiors shifted and recreated with recycled objects, six-meter long polyurethane silk worms to sit on, audiovisual instrumentation such as overhead projectors, a Super 8 camera and strobe lights. My mom tells me that they would get random engine pieces from junk yards and juxtapose them with water, food coloring and oil on the overhead projectors. She would create light shows, moving them to the beat of the music. The people made the place: those who ran it, those who performed and those who attended.

From utopia to reality

My father and his university friend Carlo Caldini teamed up with Mario Bolognesi, who had owned the neighborhood coffee shop where Fabrizio grew up. At the beginning, my dad was in charge of the artistic direction, Mario took a more business role and Carlo, who was still finishing his military service, helped to develop the creative concepts. The summer of 1968 was spent searching for the right place until they came across a former engine repair shop that had been damaged during the flood of 1966. It was in via Palazzuolo, in a neighborhood we would call “popolare” in Italian. The place was covered in mud, soot and debris like dead birds. They all rolled up their sleeves, my mom included, and got to work. I found footage of this, too.

At the time, my dad and Carlo were part of the 1999 Radical Architecture movement, formed by seven members, which later became known as the 9999 group, consisting of the three original members (my dad, Carlo and Paolo Galli) and joined by a new member, Giorgio Birelli. The other 1999 members were all there at the infancy of the Space Electronic, often involved in some way, such as Mario Preti with the marketing. They used Giovanni Sani’s father’s construction company, who built the iconic balconies as well as the second ramp that leads back up to the main dance floor. The ramp that brings you down into the mouth of the Space is an original remnant of the engine repair shop: a game of mirrors that my dad developed. His experimentations with specchi continued in other footage he shot of Florence, and in his feature film, Il Minotauro. Playing with how we see ourselves and one another was something the group also explored through the closed-circuit cameras placed outside that would show you who was entering and exiting.

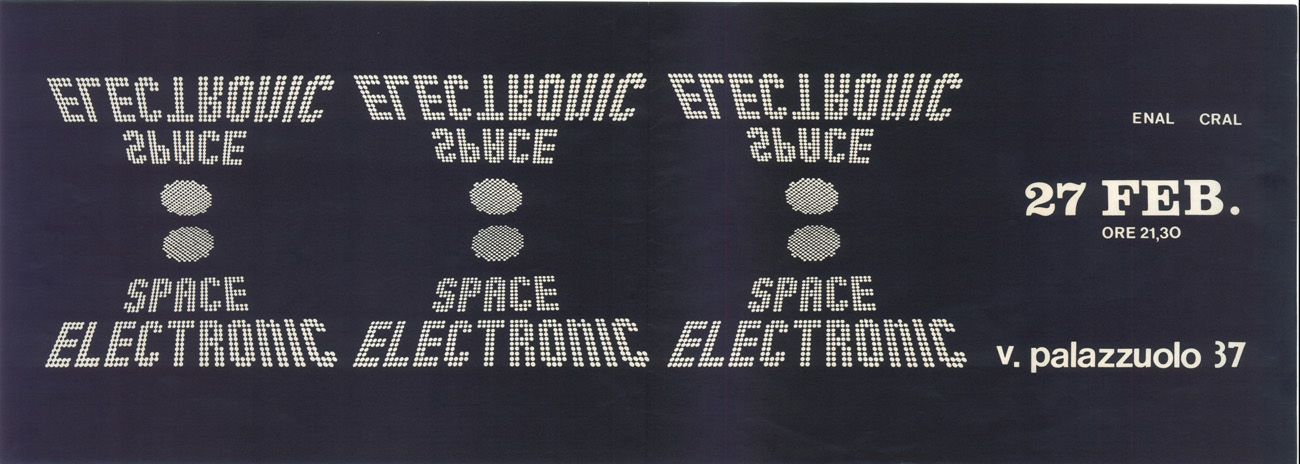

The opening

The Space opened on February 27, 1969. Five months later, people watched man land on the moon on those closed-circuit TVs at the Space, the same summer that Woodstock happened for the first time. As the music critic Bruno Casini explained, “The Space was one of the first places that was homebase to rock culture. I remember that if you showed up at the Space in a tie and jacket, they’d send you back home. But if you showed up in bell bottoms, Afghan shirts, t-shirts with musical groups on them, long hair, necklaces, rings and any vaguely hippy accessory, the doors would be wide open.”

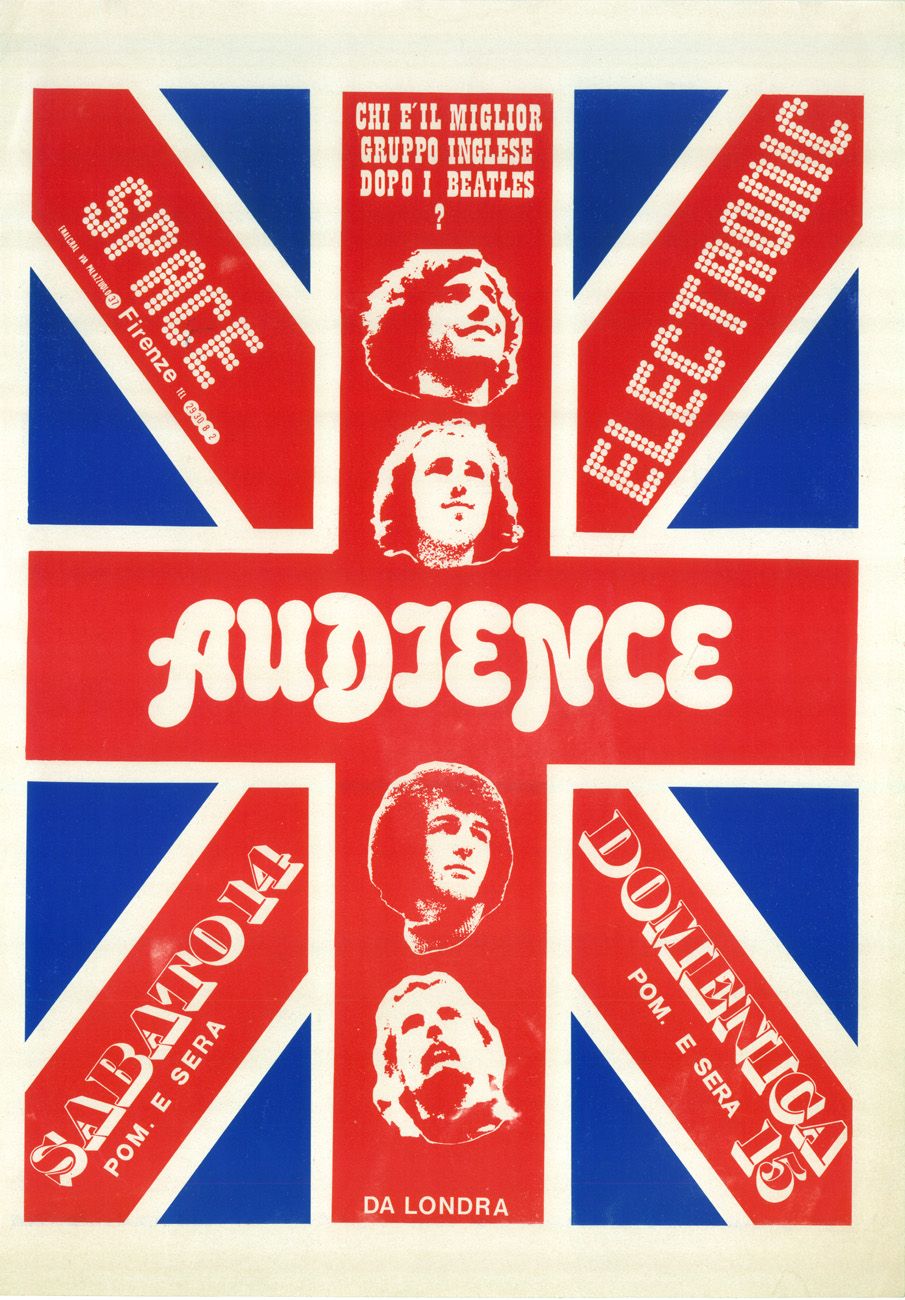

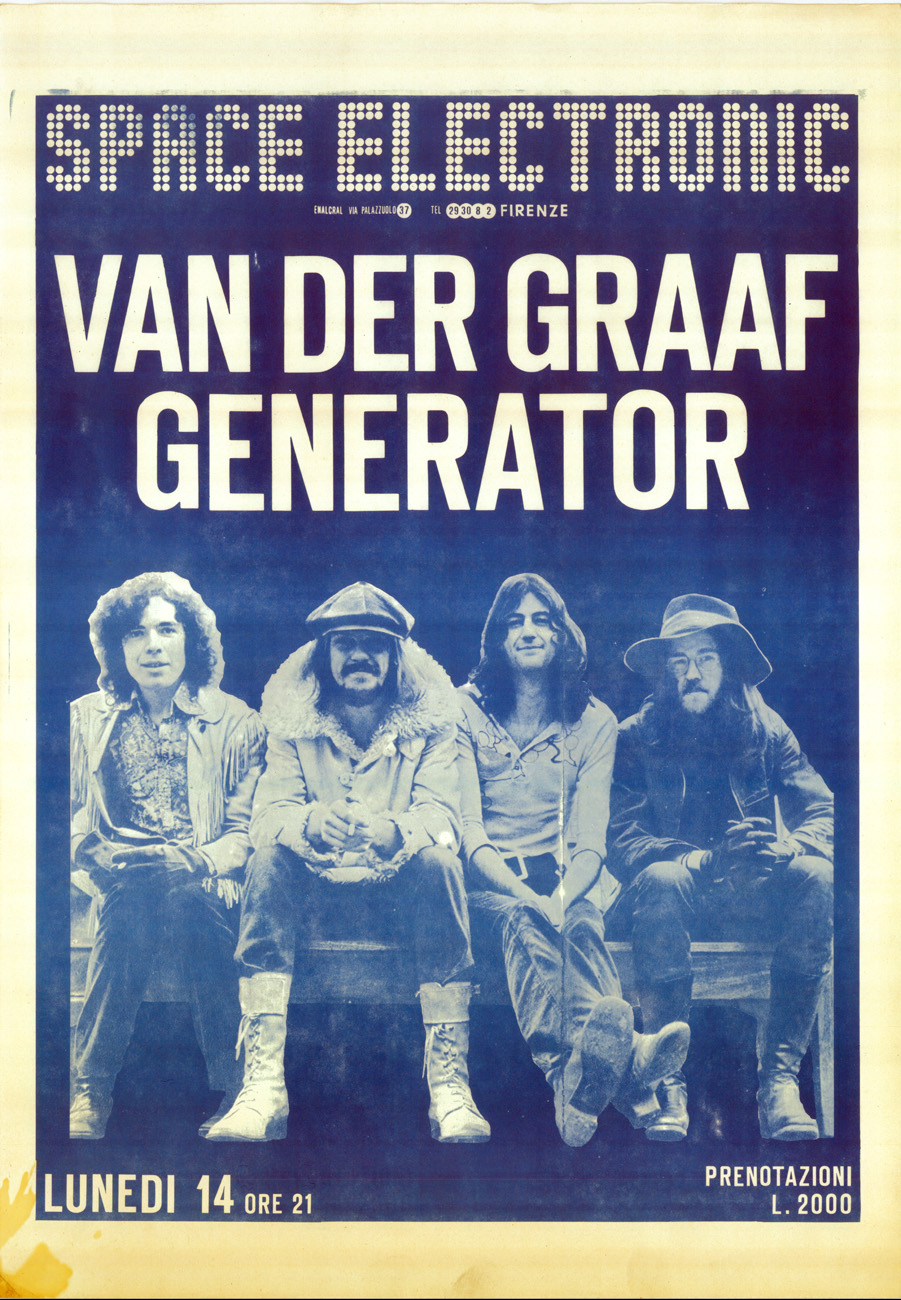

Sometimes four or five bands would perform every evening, from established groups like Theaudience to Irish multi-instrumentalist Rory Gallagher, rock bands Van Der Graaf Generator and Canned Heat, Italian beat band Equipe 84 and Demetrio Stratos’ Area. Anyone had the opportunity to perform on stage, safe in the knowledge that the audience had cultivated such a sophisticated music palette that they would be booed off stage if they weren’t good enough. But the good ones had the rare chance to have a break, which many did. It was also frequented by legends like Dario Fo and Charlie Watts, the drummer from the Rolling Stones.

Music, theater and dance

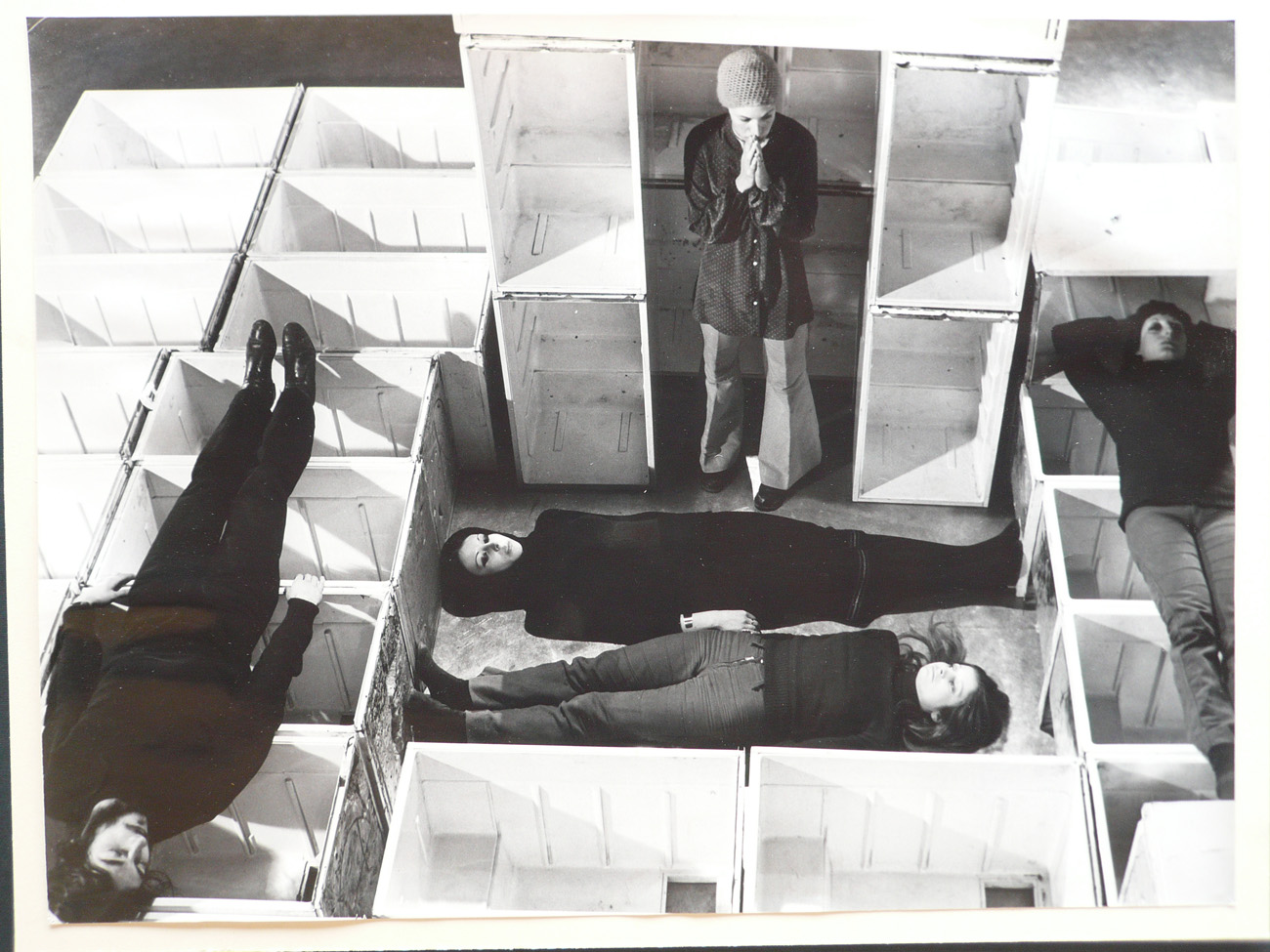

Jam Session N. 1, performance in refrigerator carcasses, S-Space: Scuola Separata per l’Architettura Concettuale Espansa. Space Electronic, 1970.

The Space was everything. It was also a place for students to experiment. A three-day event was established called S-Space, Scuola Separata per L’Architettura Concettuale Espansa, in collaboration with other Radical Architecture groups from around Europe, such as Superstudio, UFO, Street Farmer and Ant Farm. Recycled refrigerator carcasses were used to create simulated spaces or performances. They even flooded the bottom of the Space and placed stones upon which one could cross the room. On the dance floor there was a garden with real vegetables. I found footage of this too, of my sister splashing around and playing with the vegetables as my mom ate them next to her.

Not a lot of people know that the Space might have had an entirely different name. Geronimo Electronic was the other option originally on the table. According to Carlo (who continued running the club after my dad sold his part and returned every night until he passed away last year in his Seventies), my father particularly pushed for this epithet as it represented the great Native American chief who fought for freedom, but this name would have been harder to understand. Space Electronic meant progress. Obviously an Italianized American expression because normally you would not put the adjective first, but it stuck, the name and the nightclub. And the Space Electronic still exists, in its current, very different guise, nearly 50 years later.

Elettra Fiumi is a NY-based Florentine-American filmmaker. Her project, A Florentine Man, is based on the archives of her father, Fabrizio Fiumi, and of the 9999 Group, of which he was a member. A Florentine Man is a Graham Foundation grant winner. Her short film, 9999: Memoirs, which she produced, directed and edited, is narrated by Terry, Fabrizio’s wife, and is currently on view at the Rivoluzione 9999 exhibition at the Museo del Novecento in Florence. Other extracts from A Florentine Man are in the Radical Utopias exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and have been on view at the Biennale of Architecture in Venice, the ICA in London and at LACE gallery in Los Angeles.