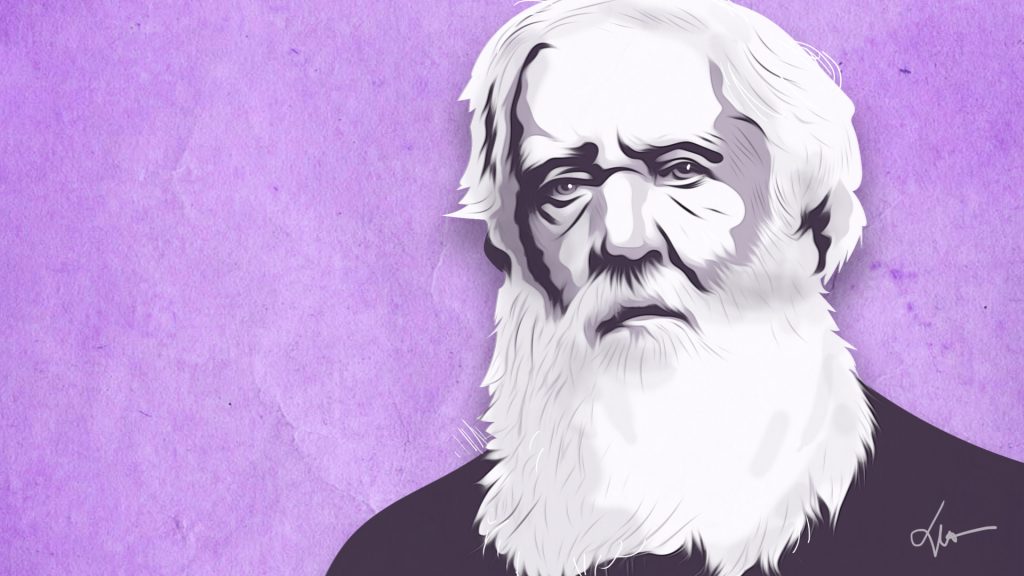

Florence and its amazing array of artworks can have a lifelong influence on many people. This was certainly the case for Austen Henry Layard, for whom art became a driving force in his life and work. Born into a Huguenot family in Paris on March 5, 1817, Layard’s grandfather was the Dean of Bristol, while his father held a high-ranking post in the civil service in Ceylon from 1800 to 1813. The young Layard was mainly educated in Europe and spent much of his early years living in Italy because of his father’s chronic asthma, first in Pisa and then in Florence, where he frequently visited the Pitti Palace and the Uffizi. By constantly sketching the art he saw in the city’s galleries and the surrounding Tuscan landscape, he soon became a talented draughtsman, a skill that would stand him in good stead when he began excavations in Babylonia. He spoke Italian and French, and later would learn some Arabic and Persian.

In 1830, the family returned to England, where Layard attended school until, at 16 years of age, he went to work in his uncle’s London law office after his father’s death. In 1838, he travelled to Scandinavia, Russia and Denmark, but having completed his studies, he decided the law was not for him. Instead, in 1839, he embarked on his first trip to the Orient. With his friend Edward Mitford, their plan was to reach Ceylon and set up a coffee plantation. They travelled overland because Mitford was afraid of taking the trip by sea. On September 13, 1839, they reached Constantinople. Adopting the dress, customs and manners of nomadic Arabs of the desert, by November they were heading for Syria and, in January 1840, they reached Jerusalem, where the two separated. Layard visited the ruins in Petra, Ammon and Gerash, where he survived an attack by Bedouin tribesmen. An accomplished writer, Layard described his early travels, saying, “I had been wandering through Asia Minor and Syria, scarcely leaving untrod one spot hallowed by tradition, or unvisited one ruin consecrated by history. I was accompanied by one no less curious and enthusiastic than myself. We were both equally careless of comfort and unmindful of danger. We rode alone, our arms were our only protection, a valise behind our saddles was our wardrobe; and we tended our own horses, except when relieved from the duty by the hospitable inhabitants of a Turcoman village or an Arab tent.”

He was reunited with Mitford when they visited Aleppo and Mosul together. There, he saw a large mound of earth on the eastern side of the Tigris river, which he initially mistakenly believed to contain the remains of Nineveh. Instead it turned out to be Nimrud, which Layard began excavating between 1845 and 1847 and from 1849 to 1851, uncovering the palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE), with its gigantic sculptures of the famous winged lions and bulls. Layard called it the “cradle of the human race”. Through the intervention of Sir Stratford Canning, the British Ambassador in Constantinople, for whom Layard had previously carried out several diplomatic missions, he was provided not only with a document authorising the excavations, but also the removal of the sculptures. Layard had the bas-reliefs sawn in half to make them lighten, so they could be floated the 600 miles down the Tigris to Basra and transported another 1,200 miles by sea around the Cape to the British Museum in London, where they can still be seen today.

In 1849, Layard began excavations on the Kuyunjik mound, where he found ruins from Ancient Nineveh and the palace belonging to King Sennacherib, who reigned between 704 and 681 BCE. His book, Monuments of Nineveh: From Drawings Made on the Spot, published in 1853, contains 100 splendid engravings of the Nineveh sculptures and remains.

After seven years excavating in what was then known as Asia Minor and Syria, Layard returned to England in 1851, where he entered politics, becoming a Member of Parliament twice, as well as serving in different ministerial roles under several governments. In 1869, the 51-year-old Layard married his 25-year-old cousin Enid Guest, who was the third daughter of the ten children of industrialist Sir John Josiah Guest, who owned the Dowlais Ironworks in Wales, and his wife, Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Bertie. Enid accompanied her husband during his diplomatic postings as ambassador to Spain and later Turkey.

In 1875, Layard and his wife retired to their home, Ca’ Cappello, on Venice’s Grand Canal, which they had purchased the year before. In 1866, he was a founder of the Compagnia di Venezia e Murano, the company that stimulated the rebirth of the Venetian glass industry in Murano. Their elegant palazzo was filled with artworks, including paintings by Bellini, Garofalo and Montagna, and objects from Layard’s archaeological past and diplomatic travels. It soon turned into a magnet for friends, politicians and artists visiting Venice up until Layard died in London on July 5, 1894. Enid continued to live there until her death on November 1, 1912.

In 1913, after Layard’s widow died, Major Arthur Austen Macgregor Layard claimed that his uncle had willed him all “the portraits of myself and all my family and other portraits”. Instead, as a trustee of London’s National Gallery since 1866, Layard, who was not only an erudite art historian and a long-time collector of early Italian paintings, had bequeathed the bulk of his collection to the museum. After losing his original legal challenge, Arthur appealed to the House of Lords. It took another eight years before Arthur Layard finally agreed to accept a £17,000 settlement from the Gallery on March 19, 1917, just two and a half months before he died in a car accident.