In the complicated summer of 2020 when we had a few short weeks of relief from the frightening plague, Giovanni Giusti, co-owner of The Florentine, made contact with a certain Florentine, Claudio Bertini. Claudio and his partner, Massimo Gramigni are the producers of concerts and theatrical events at Teatro Verdi, Mandela Forum, Tuscany Hall, the stadium and especially the historic Teatro Romano in Fiesole, a 2,000-year-old natural theatre built into the hills of Fiesole, or as the Mayor of Fiesole, Anna Ravoni, says of the theatre: “It was built in the town that we call the Mother of Florence”.

I was invited to meet producer Bertini in the magnificent theatre nestled perfectly in the Fiesole hills beneath a cloud-streaked sky. When we were there, he made the point that the Teatro Romano is not an “amphitheater”. An amphitheater is round and constructed largely for sport. This mountainside semi-circle of several thousand-year-old crafted stone is a proper “theatre”, where Romans would have heard Homer’s Odyssey acted aloud some 2,000 years ago. The theatre itself had disappeared, grown over in time, but in the 1800s it was re-discovered and now resembles the same theatre our ancestors would have visited on a warm summer night. Today, the theatre is the location for the 76th Estate Fiesolana, Fiesole’s outdoor summer music and performing arts festival. On any given night, the theatre is filled with laughter, singing, pop and rock bands, theatrical acts and a large crowd, sometimes nearing 1,700 people. The reason why Giovanni Giusti had made contact with Bertini was that one day I hoped I could do something myself on that historic stage.

Not a few weeks thereafter, in that summer of 2020, my neighbor Daniel Graves and his wife, Anki, joined me for dinner. Daniel created The Florence Academy of Art, home to some 135 international students each year who study the craftsmanship of classical painting developed 500 years ago, all of whom follow in the footsteps of Michelangelo as they hone their own styles. During our evening meal, I recounted the events of the day: that I had visited the Teatro Romano di Fiesole for the first time and that one day I hoped to do something there. Daniel asked me: “Do you know the story of the three Carabinieri in Fiesole who gave their lives to save ten Italian civilians being held by Nazis? This was the summer of 1944. Apparently, some of it happened right in the theatre in Fiesole.”

The story goes like this. There had been a fire-fight between Nazis and partisans as the Nazi retreated. A Nazi died. The “rule of law” was that, for every Nazi killed, ten Italian civilians would pay with their lives. Ten civilian Fiesolans were taken to the basement of the Hotel Aurora on the town piazza. The young Carabinieri were helping the partisans, illegally collecting artillery and hiding it in their gardens for partisans to collect in the middle of the night. The risk of discovery was immediate death. The Carabinieri, now joining the partisans, went to hide in the Teatro Romano di Fiesole. They were told by the priest of the church that they needed to present themselves to the Nazis. This way, the ten civilians would survive. They had a choice. Run for their lives, or give their lives to save others. Their names were Fulvio Sbarretti and Vittorio Marandola, both 22, and Alberto La Rocca, just a boy of 20. Within an hour of being informed, they made their decision. They would never live peacefully if they didn’t save the lives of others.

I was stunned. It wasn’t just a story. I had been where this had taken place. What if any of us were in the same position? What would we have done?

I retold the story several times to Florentines, and even some Fiesolani. Very few, if any, had heard it before. Things in the world started to get somewhat darker. While the plague brought out much good in many people, it also brought out the fear of “losing control” and “rights being taken away”. The times seemed to have brought forth populist sentiments and actions, and in certain extreme cases, fascist tendencies that the western world had not seen since those terrible days of the Second World War. As I learned more about the story, there were many elements of crimes going unpunished and heroes not being celebrated, and in one particular case, the story of a daughter whose father, a Carabiniere who survived, never telling her his tale. He would never look her in the eyes. Survivor guilt, perhaps.

What if this was the story I told from the stage of the Teatro Romano? But how? It struck me that when time stands still, or rushes so quickly, either of which might have happened to these boys, those rushes and moments can be defined in music. I decided that I would compose an opera, replaying the events as they happened.

There was a publication online, the history of the Arma dei Carabinieri, with articles and an exhibition that happened in 2019 put together by a certain Jonathan K. Nelson, a professor of art history at Syracuse University. A friend, Paola Vojnovic, put me in touch. (Nelson had been her mentor at Syracuse.) Jonathan, a brilliant historian, made his way into this story via the sculpture that is exhibited in Fiesole that he was studying from an art historian’s perspective dedicated to the Carabinieri by artist Marcello Guasti. The story opened up to the scholar through historical records in Rome. The story was even more complicated and heartbreaking than originally thought. It was the story of the one Carabiniere survivor, who lived his life, guilt-ridden, perhaps, that he survived.

The story percolated in my mind for a good deal of time. In February, I asked producer Bertini if he could give me a place in this summer’s concert programming. He agreed and I began to sketch out the opera. I contacted members of the Maggio Orchestra to play, singers from the Maggio opera company to create the roles of the Carabinieri and others, and Italian designers to recreate the period looks. I contacted international opera star Nathan Gunn to play the role of the lead Carabiniere. Last week, we went into rehearsal. The story will live and be told again.

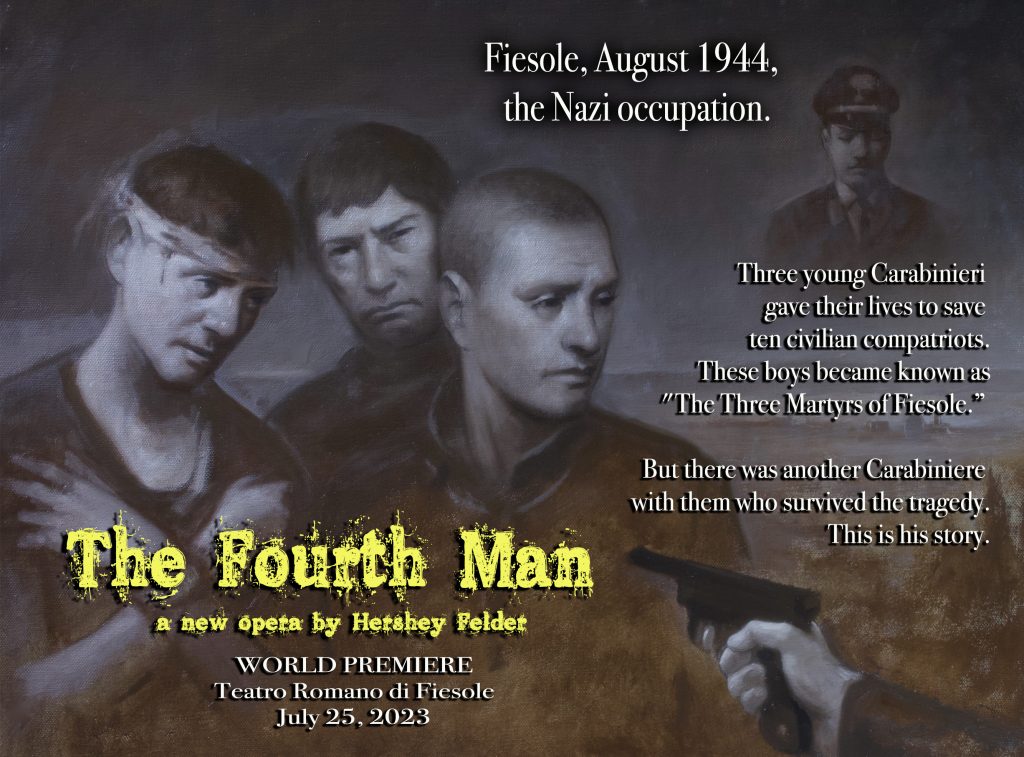

As the music took shape, I told Daniel Graves how things proceeded. He told me he would like to create a painting that captures the feeling of what happened. What a chance to have another “Graves” in the world. I told him that such a painting should hang in Fiesole. It was a sizable piece he said he wished to create, a meter by a meter and a half capturing what these boys might have felt that eve. I told Daniel that I hoped to find a sponsor for this painting, so that it could hang where it belonged. Daniel offered the painting at half of his usual fee. I hope a sponsor comes forth, as it is such a meaningful work of art, whether it hangs in Fiesole or in someone’s private collection. It is a work, pictured here of beauty, sensitivity and emotion.

What a journey this has been to come, in a short three summers, full circle!

The piece of musical-opera-theatre is called Il Quarto Uomo and the premiere will take place on July 25 at Fiesole’s Teatro Romano.

Tickets start from 17 euro for readers of The Florentine (instead of 20 euro), plus commission