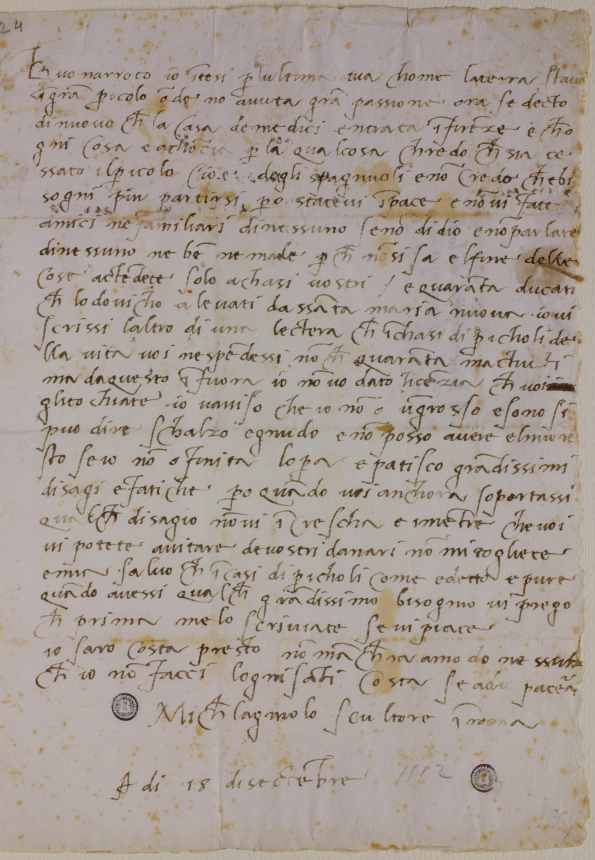

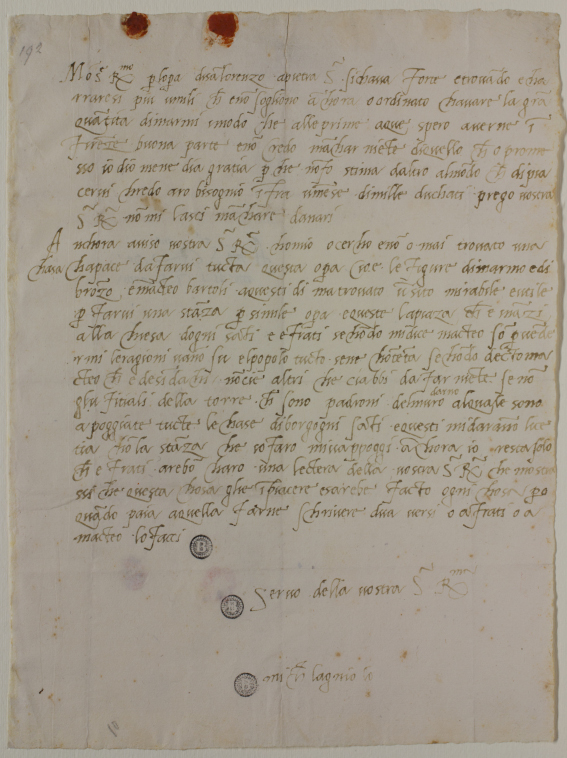

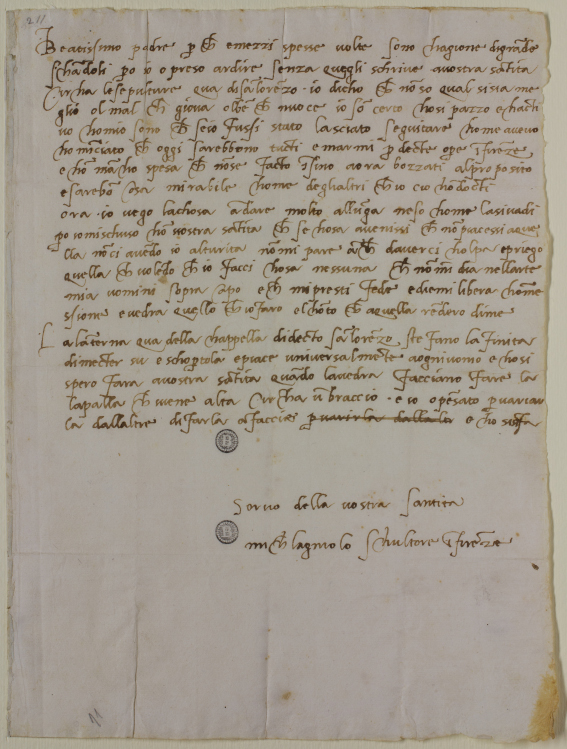

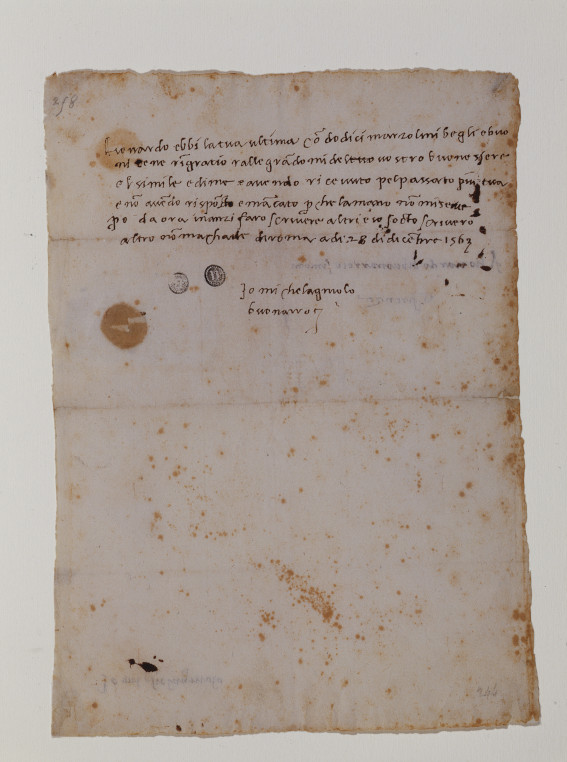

In Michelangelo’s world, paper was a precious commodity. After all, the cartoon, not the painting, counted as the real sign of mastery in being a skilful draughtsman. In fact, a master’s cartoon, on any given theme, would pass through the hands of many well-established painters, who sought to transfer the “skeleton” of a composition from paper to canvas or panel using the spolvero technique. Yet, Michelangelo’s interest in paper was not merely artistic. Indeed, the man who signed his name as scultore was a bit of a paper hoarder (when he wasn’t burning his own precious drawings for failing to satisfy his standard of perfection). No detail was too plain to explain and his vast archive at Casa Buonarroti is a mixed bag of poetry and contracts, invoice letters, and even miniature copies of correspondence he penned himself as a record of what he sent out into the world. His shopping lists, made for assistants who couldn’t really read, contain drawings, not words, and the opportunity to see one close up recently gave me a jolt of joy: he wanted both “big fish” and “little fish” for supper one day—and a true foodie would know what kind of fish he expected.

Casa Buonarroti’s director Alessandro Cecchi shares the following insight on the museum’s documents collection. “Thanks to the vast treasure trove of Michelangelo’s papers preserved in the archives of Casa Buonarroti, it is possible to retrace—almost day by day—the human and artistic story of a true artificer, whose human dimension is revealed. We discover a Michelangelo who was fragile, suspicious, touchy and sometimes choleric in his dealings with a family like his own, which he supported through his work, and learn more about his relationships with friends and patrons. Despite his being far from Florence and living in voluntary exile for some 30 years until his death in 1564, we find him preoccupied with finding a suitable home and a noble bride for his nephew Leonardo. We also see him providing for his father and siblings, all of whom he survived. Michelangelo the man emerges from these archival papers. They bring him closer to us and it certainly does not diminish the artist Michelangelo.”

Michelangelo’s “penfriends” include the likes of Catherine de’ Medici, the Florentine queen on the French throne, and Pope Clement VII, who summoned a disgruntled Michelangelo to Rome in 1534 to complete the Sistine Chapel (the Last Judgement portion, which was widely received by his contemporaries as a shocking scene of ubiquitous nudity, loaded with more pain and terror than most cared to behold). Michelangelo exchanged letters with Vittoria Colonna, one of the only female poets of the period outside of convent walls. A close friend and confidant of the master, she is described by contemporary author Ramie Targoff as being “about as free as any Renaissance woman could be”. Michelangelo corresponded with Venetian painter Sebastiano del Piombo, who unlike his Florentine colleague was more interested in color than form. (Del Piombo was ultimately written off by the master as being “lazy”, for preferring oils to fresco-work, when their wills clashed on the best technique to employ for decorating the Sistine Chapel.) The Buonarroti family archive also contains correspondence from Italy’s first art historian Giorgio Vasari, who would be largely responsible for promoting the idea of Michelangelo’s inherent divinity, affording him the title “the Divine” and crediting him as the major inspirational force behind his day’s iteration of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno.

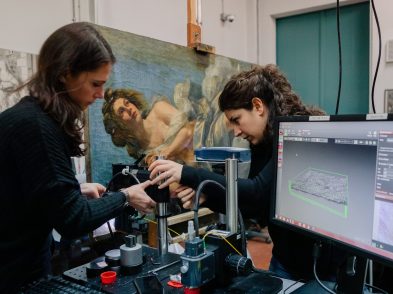

The Buonarroti Archive consists of 169 volumes and over 25,000 papers, a truly formidable family history that runs across generations, from Michelangelo’s nephews to the family’s last heir, who left the home and its precious assets to the city of Florence. All this said, the real news is revealed to those who have made it to the end. A new restoration project, focusing on Volumes IV and V of the Buonarroti Archive (342 documents) was recently launched at the museum, thanks to the support of the Ente Cambiano bank. In addition to conversation and conditioning, the project foresees the digitalization of these documents. Evviva, it’s a “high-definition” reason to celebrate for scholars.