The 1960s and ‘70s saw Italy’s transformation into an industrialised and consumerist nation. Many sections of the population changed too, including artists. The times seemed to require it. The mass media culture of television, radio, cinema, the press and advertising was having a fundamental effect on people’s lives. The world of reproduced imagery was expanding rapidly as new ways of experiencing the world were entering people’s homes. With the addition of political instability and the movement towards a liberal society, just as the economic boom slowed to a standstill, artists reacted to the upheaval by looking at materials and chose to express themselves in unconventional ways, with new techniques focusing on interdisciplinarity, combining different forms of representation in a manner echoing the explosion of artificial imagery in the public domain.

Florence was a leading centre for these innovations, primarily on account of Gruppo 70. Made up of poets, storytellers, critics, intellectuals, artists and musicians, it was linked to the Florentine experimental scene and in particular the left-wing magazine Quartiere. The founders were a mixed bunch. Eugenio Miccini had studied philosophy and theology, while Lamberto Pignotti was a semiotician and theorist of advertising. Later on, the Florentine artist and musician Giuseppe Chiari joined them, as did Ketty La Rocca, whose background had also been in music and child education, although her day jobs had included being a radiographer. The painters Antonio Bueno and Silvio Loffredo were members, as were figures in the arts like Eugenio Battisti and Gillo Dorfles.

They adopted a critical approach to the mass media, especially the passive way in which audiences absorbed them. Their eyes were turned to the future, which partly influenced the group name. Several gruppi took shape in these years in Italy and the choice of “70” distinguished theirs with its suggestion of the decade ahead. A further incentive was the existence of Gruppo 63, an avant-garde literary movement based in the south that also inspired them, with Umberto Eco among its founders, which was also challenging the values of contemporary society.

They shared an interest in communication and first came together in Florence for two important conferences held at Forte Belvedere in 1963 and 1964. These events explored art’s relationship with communication and, a year later, with new technology. Perhaps not surprisingly, words became their principal medium and, within that, poetry. Pignotti spoke about “technological poetry” capable of making use of the themes, techniques and languages of mass communication to interpret the profound changes that had taken place within society. After all, words as objects could be used by anyone, especially those previously deprived of the chance to do so, and could “fit” into all manner of spaces, not just theatres or galleries. It was Minucci who coined the term that still describes the blend of words and imagery that defined their activities: poesia visiva (visual poetry).

Words and images could be combined with performance, a relatively new area for the visual arts, but one closely linked to the 20th-century avant-garde. The best remembered of these is Poesie e no—in every sense a “happening”, and one of the first. It was performed for the first time in April 1964 at the Gabinetto Scientifico Letterario G. P. Vieusseux in Florence, then repeated in Livorno (in a theatre run by a Jesuit priest), followed by the Feltrinelli Bookshop in Rome, a cultural centre for Gruppo 63. The show included poetry readings, the projection of video tapes, the creation of posters of visual poems, the reproduction of experimental music and a series of provocative actions aimed at stimulating a reaction from onlookers. The idea of using painting and posters created a channel for posting poems in the streets and squares, directly into the places where people would encounter them, as they already did film posters and political manifestos. Art could exist on the same level, which led some to call visual poetry “guerrilla warfare” (on a par with the US Beat Generation of Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs).

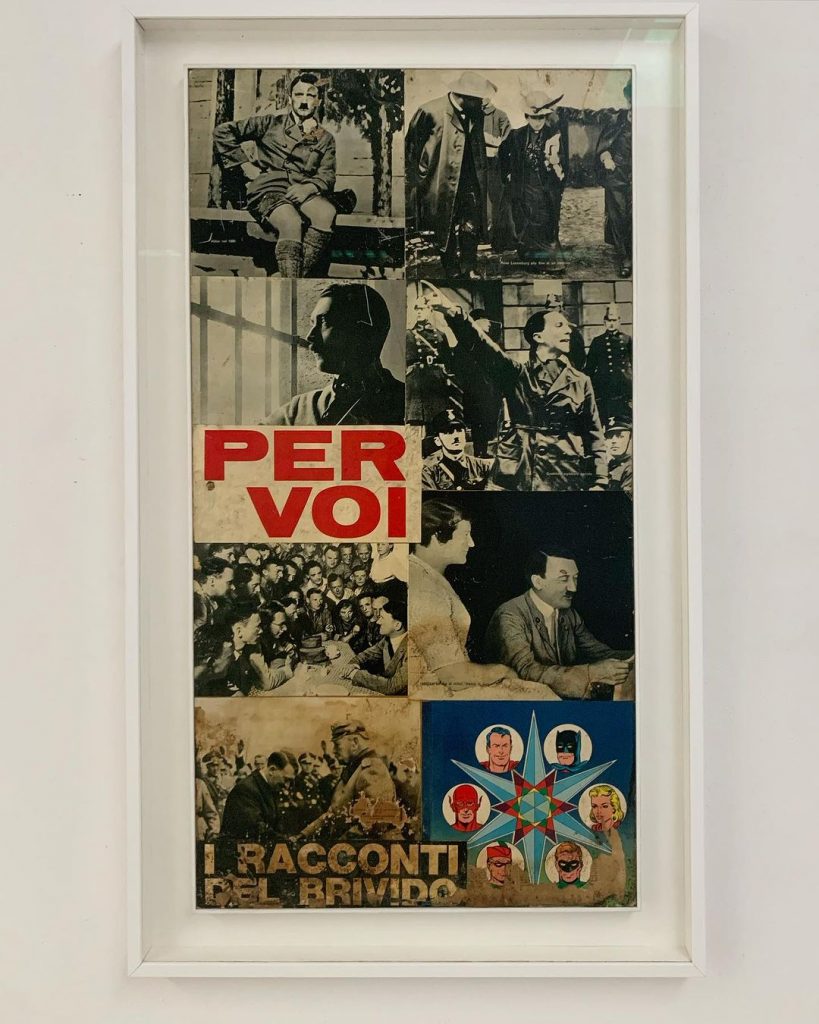

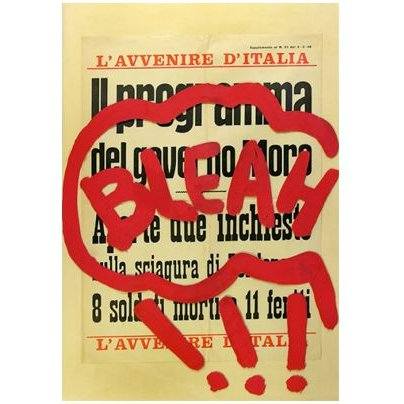

The group membership gave equal prominence to the women among them. Indeed, Poesie e no was the work of Lucia Marcucci. Born in 1933 in Florence, where she still lives, alongside Ketty La Rocca, Marcucci is one of the pioneers of Italy’s post-war conceptual art. Writer, artist, performer and activist, her work is a blend of high and low art sources in culture, literature and everyday life. There is always a combination of media, making a collage of references and materials. Poesia e no is just such a collage: on stage, songs alternate with poems and quotes. Marcucci created posters that are torn up during performances. She went on to promote visual poetry with cine-poems, photogram canvases and street-sign readymades with poetry slogans. Marcucci is a model for contemporary art practice. Her approach defines easy categorisation: the phrase “non-linear” best describes her career. “Habits bore me,” she has said, “and knowing what might happen irritates me. I need adventurous thoughts, even in the little, everyday things.” The spirit of militant criticism and protest is apparent in her output, much of which keeps this fascinating exhibition electrifyingly alive.

Gruppo 70 disbanded in 1968. In a sense, their work was done, their activism now merging with the student protests and workers’ demonstrations, placards and direct actions. Intellectuals played a significant role in protesting against the Vietnam War, and political and social protest on the left was intensifying, shocking the country. Members of the group, however, continued to operate both individually and through magazines such as Techne and Lotta Poetica. Marcucci, for instance, has remained a beacon of invention, and a voice that can be irreverent and militant in the cause of freedom.